Twitter strategy of the main Spanish political parties: PSOE and PP in 2023 autonomic elections

|

Received: 4/01/2024 Accepted: 20/02/2024 Published: 13/03/2024 |

RESEARCH

TWITTER STRATEGY OF THE MAIN SPANISH POLITICAL PARTIES: PSOE AND PP IN 2023 AUTONOMIC ELECTIONS

Estrategia en Twitter de los grandes partidos políticos españoles: PSOE y PP en las autonómicas de 2023

Javier de Sola Pueyo[1]: University of Zaragoza. Spain.

Ainara Pascual Santisteve: University of Zaragoza. Spain.

How to cite this article:

de Sola Pueyo, Javier, & Pascual Santisteve, Ainara (2024). Twitter strategy of the main Spanish political parties: PSOE and PP in the 2023 autonomic elections [Estrategia en Twitter de los grandes partidos políticos españoles: PSOE y PP en las autonómicas de 2023]. Vivat Academia, 157, 1-24. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2024.157.e1541

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The growth in the use of social networks and their advantages have turned Twitter into a crucial channel for political communication during campaign periods. The present research aims to analyze the use of this microblogging platform by the two main Spanish political parties, the Popular Party and the Socialist Party, in the case of the 2023 Aragon regional election campaign. Methodology: For this purpose, both a quantitative and qualitative analysis of 933 tweets is carried out, paying attention to the theme, function, typology, structure and interaction capacity of said publications. Results: The main findings are the observation of different degrees of personalization of content, abundant use of the social network Twitter in the form of a propaganda speaker and the absence of horizontality. Discussion and conclusions: Finally, the study allows us to conclude that, although some elements linked to creativity are observed, political parties have a notable margin to enhance the originality of their messages on the social network and, especially, the dialogue with their voters. and/or followers.

Keywords: journalism, electoral campaign, political communication, Twitter, microblogging, social media, regional elections.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El crecimiento en el uso de las redes sociales y sus ventajas han convertido a Twitter en un canal crucial para la comunicación política en periodos de campaña. Con la presente investigación, se pretende analizar el uso de esta plataforma de microblogging por parte de los dos principales partidos políticos españoles, Partido Popular y Partido Socialista, en el caso de la campaña de las elecciones autonómicas de Aragón de 2023. Metodología: Para ello, se realiza un análisis tanto cuantitativo como cualitativo de 933 tuits, prestando atención a la temática, función, tipología, estructura y capacidad de interacción de dichas publicaciones. Resultados: Los principales hallazgos son la observación de distintos grados de personalización de los contenidos, un uso abundante de la red social Twitter en forma de altavoz propagandístico y la ausencia de horizontalidad. Discusión y conclusiones: Finalmente, el estudio permite concluir que, aunque se observan algunos elementos vinculados con la creatividad, los partidos políticos disponen de un margen notable para potenciar la originalidad de sus mensajes en la red social y, especialmente, el diálogo con sus electores y/o seguidores.

Palabras clave: periodismo, campaña electoral, comunicación política, Twitter, microblogging, redes sociales, elecciones autonómicas.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Electoral campaigns in the digital era

Social networks have become political crucial tools, already essential communication channels for all parties, especially during election campaign periods (Argilés et al., 2016). This is happening in a context in which the political class needs to combat citizen rejection towards party leaders and politics in general and find ways to build new relationships with the electorate (Cervi and Roca, 2017).

With the evolution of the Internet, those responsible for political communication have increasingly horizontal tools to interact with other users, so an electoral campaign without profiles of parties and their leaders on digital platforms is hardly conceivable (Casero and Rúas, 2018). However, as Caldevilla (2009) assures, most parties are not able to use all the potential of online channels and, often, their actions remain unsuccessful attempts to reach the public.

Therefore, in recent years, the use of networks has become a crucial element for campaign teams (Calvo et al., 2019), which are responsible for developing political concepts related to a party and its candidates that satisfies voters and wins votes. As Caldevilla (2009) asserts, we are in the presence of new politics-making ways that seek to dialogue and interact with society, while trying to adapt to the changing digital era.

According to Bustos and Ruiz (2016), among all the social networks used in politics, Twitter[2] stands out. This creates a new space in which parties can deliver information directly to their audiences (López, 2016), without anyone modifying or manipulating the message.

1.2. Twitter as a means of political communication

Since its introduction in 2006, Twitter has become the most relevant social network for political parties (Mancera and Pano, 2013), including services of other platforms such as "email, instant messaging, news syndication and blogging" (Herrera and Moya, 2015, p.3).

Twitter is a digital and social platform for information, engagement and dialogue in the political arena, which allows direct and real-time conversations between party representatives and the rest of the citizens (Mancera and Pano, 2013). Pérez and Zugasti describe it as an "asymmetric, light, decentralized, global, hypertextual, intuitive, multiplatform, synchronous, social and viral" (2015, p.2) channel that favors public debate. García and Pérez (2020a) add other peculiarities such as the responsiveness and influence of citizens, who begin to appear in the political speech. Gelado et al. (2019) claim that the interactive potential of this social network drives a radical change in the communication of politicians on the Internet, providing an opportunity to close the gap that separates them from the voters, increasingly disappointed with the way the lawmakers transmit messages.

On the other hand, Gamir (2016) highlights that Twitter is characterized, mainly, by its potential interactivity, the aforementioned content-spreading immediacy, the easy access of any user to all the information, the horizontal interaction among different profiles, the ability to customize posts, its multimedia nature, the possibility of feedback and the public nature of all messages. Thus, he assures that it is a perfect instrument for opinion leaders to set guidelines in the public agenda.

However, most authors agree in highlighting Twitter’s bidirectional character as its better feature in the field of political communication (Guerrero and Mas, 2017). This concept is understood as the possibility of exchanging all kinds of messages directly and receiving feedback from other individuals (Alonso et al., 2016), which creates new communication channels between parties and citizens, and changes their relationship dynamics (Alonso et al., 2017). In tweets, the electorate can see a more spontaneous and authentic side of the candidate, which creates a conversation-like atmosphere between politicians and citizens (Díaz et al., 2016). This two-way dialogue promotes feedback and improves mutual understanding between leaders and their voters, consolidating the profiles of parties and their candidates.

In short, all these features, advantages and possibilities Twitter offers to those responsible for political communication, along with its more than 200 million users, have turned it into a platform open to debate, dialogue, exchange of information, direct contact, etc., crucial in any electoral campaign (Berzosa et al., 2019; Bustos and Ruiz, 2016). Through Twitter, parties can organize high-impact campaigns in shorter periods of time with lower budgets. They can also issue electoral information, statements of their leaders and mobilize votes. Those are the main reasons why it has become an essential channel in politics (García and Pérez, 2020b).

Casero et al. highlight that this microblogging platform has four crucial functions for parties: 1) to spread information related to their campaign events and their statements in the media in the form of self-reference (when a politician announces his/hers presence at rallies); 2) to be able to mobilize the electorate and participation in political events, through specific requests (when a politician asks people to vote); 3) to interact with the different audiences on the network, based on two-way communication and dialogue between leaders and citizens; and 4) to personalize the profiles, allowing them to differentiate from other accounts with the use of different structures and content in their tweets.

Likewise, as Alonso et al. (2021) assert, this instrument has a very important function when it comes to the relationship between the parties and the media. In addition to have their charismatic appearances broadcast, most political figures use Twitter to generate headlines and gain be present in mass media, which increases the visibility of the message they want to communicate. In this digital platform, political figures have also discovered a tool to mobilize their voters. They persuade the electorate through various communicative techniques to spread content, attend events, go to vote, etc., (Donstrup, 2019) They can do all this away from the scrutiny of journalists and the media filters, since this social network is an unmediated channel for political communication (Herrera and Moya, 2015).

1.3. Spanish electoral campaigns on Twitter

The boom of social networks in the field of politics began in 2008, with the cyber electoral campaign carried out by Barack Obama's communication team in the U.S. presidential elections (Alonso et al., 2017). After its success, politicians around the world began to see the Internet and digital platforms as very useful tools to convey their messages and to catch their electorates’ votes (Alonso et al., 2016). In Spain, as Alonso et al. (2016) assert, some parties had already begun to use Twitter in the municipal and autonomous elections in the Basque Country, Galicia and Catalonia between 2009 and 2010. However, it was in 2011 that this social network was incorporated as an essential element of political communication.

Authors such as Gamir (2016) or Mancera and Pano (2013) agree that the 2011 elections marked the consolidation of the use of Twitter as a political communication channel in Spain. During the campaign, this platform mainly served as a bulletin board and a speaker to keep people informed about electoral events and agendas. These pieces of advertisement were mostly aimed at profiles within the same political party and established a minimum level of interaction with other users through mentions and hashtags (Sabés and Zugasti, 2015). Abejón et al. (2012) state that politicians understood that it was very important for them to have social network accounts, but were not able to take advantage of all their potential or to communicate efficiently with citizens through real interaction.

The emergence of Podemos (Spanish political party) on the national scene and the campaign for the European Parliament elections in 2014 produced an upturn in the use of social networks for campaigning, in which the dialogue between this party and its supporters stood out (Pérez and Zugasti, 2015). Meanwhile, most parties' actions focused on promoting campaign events and not on talking to users (Congosto, 2015).

During the election campaign periods for the 2015 regional and general elections, political parties made use of Twitter again as another propaganda channel. However, they continued ignoring its benefits, following traditional communication strategies and reproducing the same information patterns as through the rest of the media (Calvo and Campos, 2017; Capdevila and Machado, 2017). Parties did employ more multimedia interactive elements such as retweets, mentions and hashtags (Calvo, 2017), however, they failed at exploiting these features’ dialogue potential (Díaz and Marín, 2016).

There were no significant changes in 2016 elections, in which the use of the social network was closer to conventional politics than to cyber politics, without adapting to the digital environment (Berzosa et al., 2019). Despite the fact that parties increasingly used more combinations of post elements -text, images, videos, links, mentions, etc.-, they followed uniform and poorly personalized structures that failed to distinguish one party from the rest (Guerrero and Mas, 2017). Each party’s posts glorified their own proposals, values, ideology and candidates, criticized their adversaries and mobilized participation. These posts were self-referential and meant only for inner interactions (García and Zugasti, 2018; Suau, 2020).

According to Renobell (2021), for the 2019 autonomous and general elections, Twitter profiles of political parties were more original and had a more intense activity during the electoral campaign. Although they continued to increase the use of multimedia elements and tweets with their own content, they kept interacting within their own partisan and media environments, neglecting Twitter’s communicative potential once again (García and Pérez, 2020a).

Currently, politicians are evidently aware that they have a lot at stake in social networks and must therefore adapt to the digital environment to communicate with their voters. However, they are not yet able to take full advantage of the platform to reach citizens effectively (Peris et al., 2020).

2. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND HYPOTHESIS

The present study aims at analyzing and comparing how the Socialist Party and the Popular Party (the hegemonic political parties in Spain) used Twitter during the campaign for the 2023 Aragon’s regional elections. In order to achieve this, the authors propose the following objectives:

O1. To study the communicative behavior of each party during the selected period, paying attention to each post’s theme and functions.

O2. To examine the use of Twitter resources (images, videos, links, buttons, hashtags and mentions) to determine whether the parties exploit all of the platform’s potential.

O3. Quantify how horizontal Twitter interaction is, through the study of parties' retweets, likes, comments, links, buttons, hashtags and mentions, with whom they interacted and in what way.

In this regard, the authors propose the following hypotheses:

H1. The number of posts increases as election day approaches However, the parties respect the day before election and are not excessively active on the day after either.

H2. Parties use Twitter, mainly, to promote electoral events, criticize the rest of the parties, present their programs and as a means to call for votes; but not to chat with their voting communities.

H3. There is personalization, but they do not use the full extent of Twitter’s potential in this regard. Most of the posts are original and use text, which would imply a professional handling, at least in part, but not completely.

H4: PP (Popular Party) and PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) do not engage on horizontal communication with their constituents on Twitter. They post official accounts and leaders’ online and media content, but do not interact with citizens.

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve these objectives and to verify the certainty of the hypotheses, the authors carried out a quantitative content analysis -to determine the number of actions, their frequency, typology and structure- and a qualitative analysis -to differentiate the subject matter, function and interaction in each unit of analysis-. As stated by de Sola (2020), content analysis allows to explain and systematize the actions of each profile, thus obtaining objective and rigorous results. And, whereas quantitative analysis makes it possible to measure and quantify the reality studied on the basis of the data collection, qualitative analysis facilitates the interpretation of the meaning and motivations of the subjects’ actions (Sánchez, 2005).

The research sample comprises all actions developed on Aragon’s PSOE and PP Twitter profiles between May 11, and May 29, 2023. The study covers the entire election campaign, plus the days before and after voting, in order to check if there is any difference in the volume of actions at each moment. In total, the authors processed 993 units of analysis: 551 from PSOE and 442 from PP.

The authors selected those two parties because they have received the majority of votes during Spain’s recent general, autonomic and municipal elections. They chose to focus on the Community of Aragon because they are interested in verifying the autonomic phenomenon and because, in addition, Aragon has traditionally worked as a paradigm for the whole country, so much so that it has been called the Spanish Ohio (Equipo Piedras de papel, 2015).

The authors performed daily and manual data collection, considering each action in the profiles as an individual study unit. To categorize the variables, the authors elaborated an analysis code based on the recently consulted contributions of the following authors: de Sola et al. (2021), Berzosa et al. (2019), Calvo (2017), Casero et al. (2017), Guerrero and Mas (2017) y Suau (2020).

The analysis code includes both formal and content variables[3]. Regarding the former, and as presented in the Results section, they include: day and time of posting, and use (or not) of text, photograph, video, tags, hashtags, links and buttons. As for the content, the code examines the subject matter of posts (whether it is about a campaign event, a party achievement, an attack on another party, the mobilization for voting, protocol events, relations with the media, electoral results, the personal life of the candidates or other aspects), its typology (whether it is a tweet, a retweet, a comment or a like), whether parties post their own content or content from other sources, and what function it fulfills (dialogue, information, propaganda, etc.) or what relationship it establishes with other users of the social network.

To check the reliability of the analysis code, the authors carried out a pretest round at the beginning of the research with a twofold objective. First, the authors wanted to check if they had properly set all the variables and values assigned to them, and if those variables were mutually exclusive and thorough as a whole. The second objective of the pretest round was to make sure that the two coders operated homogeneously, as it was the case. Thus, each researcher separately applied the analysis code to the first ten units of analysis posted by both parties on May 12, 17 and 21, all three randomly selected dates. In total, therefore, the authors studied 60 analysis units with the same result: the code worked correctly in all cases and the results both researchers obtained in their individual analyses coincided in 100% of the cases.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Formal aspects of the coverage

First of all, it is worth highlighting that both profiles were very active. Aragon’s PSOE profile registered 551 actions and Aragon’s PP registered 442 actions in only 18 days; which means an average of more than 30 and 24 actions per day, respectively. These data also show PSOE used Twitter more often, with 109 more posts.

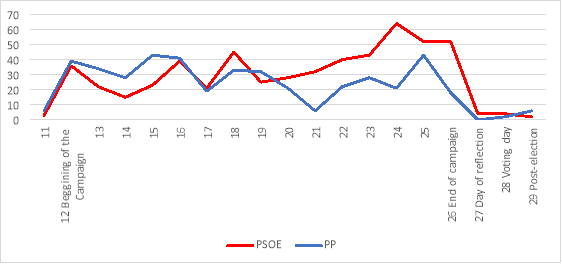

Figure 1 shows that the trajectory of the lines connecting the dots with the number of daily posts has similarities between the two parties. The number of posts skyrockets on the first day of the campaign, shows ups and downs and peaks over the following two weeks, and then falls again at the end. It is noteworthy that, whereas PSOE’s last day of intense activity was the day 26 (52 posts), PP’s occurs earlier, on the day 25 (43 posts), with 18 posts on the day 26.

Both parties show low activity on the last day before the beginning of the campaign period, May 11, with 3 actions by the socialists and 6 by the Popular Party. On the other hand, although throughout the first week of the campaign there is a somewhat notable variation, with more actions by @pparagon. The biggest difference occurs during the second week. Between days 12 and 18, the Popular Party and the Socialist Party carry out 237 (about 54% of the total) and 201 (more than 36%) actions respectively, but between the days 19 and 26, there is a big change, with 191 posts by PP (just over 43%) and 336 (almost 61%) by PSOE.

Figure 1.

PSOE and PP Twitter shares by day.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Likewise, both @pparagon and @aragonpsoe respect the day before election (27/06), with no posts by the former and 4 by the latter -with no campaign function-; they are quite inactive during the election day (28/06), mainly with thank you posts; and share very little content on the day after election day, only 6 by the winner of the elections (PP) and 2 by the second most voted party (PSOE).

Figure 1 also show some noteworthy activity peaks. The Popular Party, for example, has peaks of activity on the days 12, 15, 18, 23 and 25, which exceed their daily average (24). On the 12th (39 posts) was the beginning of the campaign period. On the 15th (43 posts), there was an interview to Jorge Azcón -candidate to the Government of Aragon- on Estado de Alarma TV and a debate on Aragon TV. On the 18th (33 posts), there was a meeting of Pedro Sánchez -president of the Government of Spain- in Zaragoza. On the 23rd (28 posts), there was with an interview to Jorge Azcón in Aragón Radio. Finally, on the 25th (43 posts), there was an interview of the candidate in Aragón TV, another one in Cope Zaragoza and the post of information about an alleged case of corruption within PSOE-Aragón in several media.

In the case of PSOE, there are notable peaks on the days 12, 16, 18 and 24. On the 12th (36 posts) was the beginning of the campaign period. On the 16th (39 posts) was the presentation of the socialist candidacy for the Andorra City Council. On the 18th (45 posts), the was a meeting of PSOE’s national Secretary General, Pedro Sánchez. Finally, on the 24th (64 posts, its daily maximum in the period analyzed), there was an interview with Javier Lambán -socialist candidate for the Government of Aragon- on Aragón Radio, a meeting in Zaragoza and another one in Barbastro.

The authors also discovered a great difference when analyzing the more active hours of each party’ profiles. While the Socialist Party seems to follow a fairly marked time pattern during the two weeks of the electoral campaign, the authors could not observe any specific pattern in the case of the Popular Party. It is also striking that Aragon’s PSOE shares its first tweet at 00:11, only 11 minutes after the beginning of the campaign. Moreover, after this, it creates a thread through 10 comments, posted in a row until 00:14. However, Aragon’s PP does not make its first post until 12:55 of the same day.

The account @aragonpsoe spreads contents throughout the day, from 08:00 to 23:00, approximately. Spontaneous actions linked to rallies and other types of campaign events appear; however, there is a recurring pattern in this profile. Except for the 12th, the other 14 days they tweet a post with their daily schedule of events around 08:30. Something similar happens between 20:00 and 20:30, with posts every day -mainly about events and statements- and, for the most part, they generate long threads with comments to offer more information. There are patterns and similarities also in the contents around 10:00, 11:00, 12:00, 13:00,17:00,19:00, 21:00 and 22:00, which coincide in at least 10 days.

The case of @pparagon is very different. This profile only makes a post before 09.00 on the 26th to share a piece of news, then shares more content in the afternoon and only tweets regularly around 14:00 (7 days) and 21:00 (9 days). It does not usually generate threads either, except on the 15th, the day of the debate on Aragón TV.

4.2. Subject matter, function and typology of posts

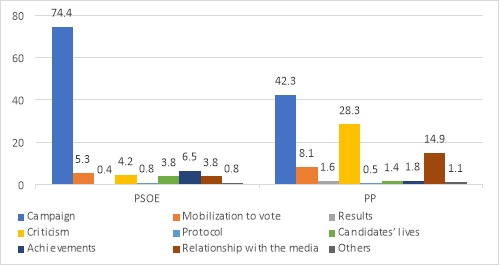

In general terms, the two parties prioritized the campaign as their most popular theme. In most cases, they both spread electoral information, campaign messages and agendas, statements by their candidates and representatives, appearances in the media, etc. Although both parties use this type of content as the main theme for their posts, there are differences: PSOE did so in 74% (410 posts) of its actions; PP, in 42% (187 posts).

Figure 2.

Main theme of the posts (in percentage).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

PSOE also stands out, although to a lesser extent, for uploading posts about its achievements as a party and those of its candidate, which represents nearly 7% of its total actions, while PP only devotes 2% of its posts to the same. On the other hand, the Popular Party issues abundant criticism in more than 28% of its posts, while Socialists only do it in little more than 4% of the cases.

The Popular Party also stands out at interacting on or with the media (almost 15% of posts) and in search of mobilizing the electorate to get votes (more than 8% of posts), while Socialists do the same less than 4% and 5%, respectively. In both profiles there are images, videos and texts with statements, extracted from interviews, participation in debates, public statements, etc. Likewise, in both profiles there are posts that directly urge citizen to go to polling stations. It is worth mentioning these two parties did not ask the people from Aragon to go to the polls, they rather ask for people’s votes directly.

As for the function of the posts, closely linked to the topic, the authors also found several similarities and differences. Both parties issue self-propagandistic posts in most cases (higher in the case of the Socialist Party, with more than 72% compared to almost 45% of the Popular Party), which coincides with the campaign theme. Both the Socialists and the Popular Party use Twitter as a speaker to launch electoral messages, consolidate the image of their representatives and their own image, spread information about their campaigns and broadcast the statements of their representatives in the media in the form of self-reference. On the other hand, criticism has a counter-propagandistic mission, 29% of which comes from the opposition party and 4% from the ruling party. The videos with direct attacks from the Popular Party against PSOE are self-explanatory. Both parties use the platform with an informative intention.

Thirdly, they present proposals and elements of their electoral programs, some pieces of news, employment statistics, etc. 16% of PP’s posts have an informative purpose, while PSOE does it 14% the times. Finally, and to a lesser extent, the @aragonpsoe and @pparagon publish content with an emotional function in similar quantities, about 10%, to bring the candidates closer to the voters.

It is worth mentioning that neither party takes action to begin a conversation or a dialogue with other accounts, except for those related to the parties themselves or the media in which they appear.

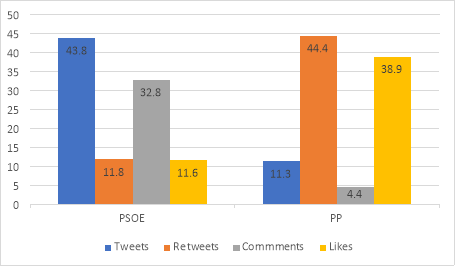

Finally, with regard to the typology of the actions on the microblogging platform, there are also many differences (Figure 3). On the one hand, PSOE posts much more of its own content -almost 77%, with 241 tweets and 181 comments- than content from others sources-just over 24%, with 65 retweets and 64 likes-, with a high degree of personalization. On the contrary, PP uses more content from others sources -more than 83%, with 196 retweets and 172 likes - than its own content -almost 17%, with 50 tweets and 24 comments-, with a low degree of personalization.

Figure 3.

Typology of the posts (in percentage).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

4.3. Characteristics of parties’ own posts

By analyzing tweets and comments (parties’ own content), the authors determined that, according to the structure of the posts, it is very common for the two accounts to use various Twitter elements. Thus, both the Popular Party (with a total of 74 own posts) and the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (with a total of 442 own posts) include multiple audiovisual elements: photographs and videos, hypertexts (links and buttons), mentions, hashtags, and different combinations of them. They also include longer or shorter texts, within the limits of 140 characters.

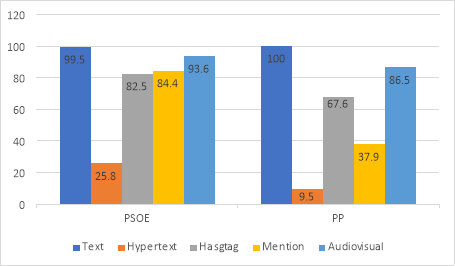

Figure 4.

Use of the different Twitter functionalities in each publication (in percentage).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

However, once again, the data reveal a very different communication strategy between @aragonpsoe and @pparagon, as the former includes a wider variety of elements in its posts. For example, PSOE adds a large number of mentions (in more than 84% of the cases) and hashtags (in about 83%), while PP uses tags in almost 68% of its own posts and only refers to other profiles in less than 38%. Furthermore, although the use of hypertexts (links and buttons) is not common for either of the two accounts, it is once again the Socialist Party which incorporates them more often, almost 26%, while the Popular Party does so in less than 10%.

As for the structure of its own content, PSOE usually uses three basic structures in its posts. The first structure, present in more than half of the posts (almost 51%), the account incorporates text, images, mentions and hashtags; the second includes text, images and mentions (more than 11%); and the third one present text, images, links, mentions and hashtags (almost 11%). On the other hand, Aragon’s Popular Party uses more varied structures in its posts. In just over a quarter of its tweets and comments (nearly 26%) it chooses to create content with text, images and hashtags; it also uses a combination of text, video and hashtags (nearly 19%); and a third variant features text, images, mentions and hashtags (more than 13%). Most often, both parties favor the use of this third structure.

Neither do the profiles coincide in the audiovisual elements, which are included in the vast majority of the publications of both parties. While the Socialist Party makes much greater use of images than videos, with 364 versus 31 (84% difference), the Popular Party publishes both types of content in a more homogeneous way and, although it also prefers photos, it only does so with a 19% difference with respect to videos (38 versus 26).

The socialists use a large number of photographs of events, such as rallies, to complement the statements transcribed in the texts, images in the form of posters to present the campaign agenda and some photos of visits to companies and institutions. They use videos to transmit more emotional information, achievements and proposals. Likewise, the Popular Party prefers to display the statements of its representatives and criticisms against PSOE through videos, and usually uses images to show visits to different municipalities and to present the program of its events.

According to the authors’ findings, the two parties employed hypertexts in different ways and quantities, although it was the feature they used the least. The socialists, who included this form of content in just over a quarter of their posts, preferred links (in more than 75% of the cases). The Popular Party, which included hypertexts in less than an eighth of its own content, chose buttons -which show part of the information before clicking on them- in almost 86% of the cases.

Thus, in the profile of @pparagon there are more than 70% of hypertexts linked to websites or other social networks of the party and its representatives (Twitter and Instagram), and the rest are linked to media or journalists’ websites and networks (interviews with candidates, debates and news that criticize the opposition). The percentage of @aragonpsoe is very similar in the case of platforms related to the party (websites, Facebook and YouTube), about 72%, but it decreases to 11% in relation to mass media (interviews to candidates and debates). In addition, the socialists attach links and buttons to another type of online content, flick.kr (more than 17%), a platform for storing and publishing images, in which they usually upload rally photos.

In no case are hypertext forms found that lead to other profiles, websites or platforms of citizens, experts, opinion leaders, institutions or organizations outside each of the parties.

As for mentions, a key indicator of interaction, the case of the PSOE is much more notable. The Popular Party writes a total of 49 @ in 28 publications, corresponding to 18 different profiles. In contrast, the Socialist Party uses the mention 484 times in 356 posts, of which only 46 are unique. Both @pparagon and @aragonpsoe use this tool to interact with profiles related to their respective political formations, extol the image of their candidates, recognize the work of their representatives, etc. In none of the cases is the possibility of dialogue and contact with the electorate taken advantage of, since, except in 3% of the mentions of the PSOE, there are no references to profiles outside the parties.

The profiles @pparagon mentioned the most are: @Jorge_Azcon (22) -the popular candidate for the presidency of Aragon- and @EstadoDAlarmaTV (8) -an online media company in which Jorge Azcón is interviewed on several occasions-. On the other hand, @aragonpsoe accumulates a large number of mentions to its representatives, especially to @JLambanM (276) -socialist candidate for the presidency of Aragón-, @lolaranera (45) -socialist candidate for mayor in Zaragoza- and @MaytePerez2 (23) – Aragon’s acting Minister of the Presidency and Institutional Relations and a candidate to Courts-.

It is also worth mentioning that, in the case of comments, the two profiles studied follow the same pattern, reacting only to their own tweets. They only use this tool to create threads (a chain of posts with progressively-increasing information about a topic) from the posts in which they had not been able to fit everything they wanted to communicate in the maximum 140 characters allowed by the platform. They usually did this when they broadcast statements from rallies in which several party representatives spoke and in debates between candidates. While the Popular Party comments 24 times, the Socialist Party does so on 181 times.

Hashtags are one of the elements both @aragonpsoe and @pparagon used the most. However, at this point, author found one of the most differentiating patterns between the Socialist Party and the Popular Party. The former includes the amount of 600 tags in 348 posts (of the total of 442 own posts), 104 of which are unique (just over 17%). On the other hand, the Popular Party includes 135 hashtags in 50 posts (out of a total of 72 own shares), only 13 of which are unique (less than 10%).

The authors observed differences not only in the number of hashtags varies, but also their content. PSOE uses almost half of the tags for campaign content (with slogans such as #LambánConVozPropia), also incorporates more than 100 locations, specific topics (#educación (education), #cultura (culture), #empleo (employment), etc.), names of party members without a Twitter profile, requests for votes, mentions to the elections and debates and, in less than 1% of cases, criticism against opponents. The Popular Party, however, chooses to use hashtags, in most cases, to ask for the vote (up to 51 occasions), talk about the debate, criticize the Socialist Government (#QueNoTeEngañen [Don’t let them fool you]) and campaign (#AragonPorEncimaDeTodo [Aragon above all]), but to a much lesser extent than PSOE.

The tags PP used the most were #VotaAzcon, #VotaPP and #DebateATV28, with which they directly ask their followers to vote for the popular candidate and his party, and as a means to follow an event, in this case, the debate. PSOE makes abundant use of official campaign hashtags, such as #AragónConVozPropia [Aragon speaks out], followed by others with locations, such as #Aragón and #Zaragoza.

4.4. Features of other users' posts

Finally, to understand the importance of interaction and dialogue capacity in campaign strategies, it is necessary to study the retweets and likes to other users’ posts. First of all, it is worth remembering that these actions account for more than 83% of the Popular Party’s posts and only 23% in the case of the Socialist Party (a 60% difference). The parties do not have similar proportions of each form of interaction either, since the Popular Party prefers retweets (196, more than 53%) over likes (172, almost 47%), the Socialists make almost the same use of both types of tools (65 retweets and 64 likes).

However, both parties are very similar when it comes to the profiles they retweet. Both tend to recognize and praise posts of their own representatives and groups -either national or local-. PSOE does so in almost 94% of cases and PP in more than 92%.

The Popular Party’s most retweeted accounts are @Jorge_Azcon (more than 41%) -Popular candidate for president-, @ppopular (more than 13%) - national party profile- and @ChuecaNatalia (more than 12%) -Popular candidate for mayor in Zaragoza-. PSOE’s most retweeted accounts are: @JLambanM (almost 67%) -Socialist candidate for president-, @PSOE (more than 9%) - national party profile - and @zaragozapsoe (almost 8%) -local party profile in Zaragoza-. The authors observe the use of similar strategies: each party focuses on users within their respective political circles: First, they highlight the image of the regional candidate; then, they do the same with the party at the national level; and, third, they praise the representatives of their party in Zaragoza.

Furthermore, in the study of the number of likes, an almost exact strategy can be seen in the case of retweets, both in the case of the socialists and in the case of the Popular Party. They mainly liked their own parties, candidates and representatives’ posts. The Popular Party does so almost 94% of the time, and PSOE, more than 92%. Likewise, the Popular Party and the Socialist Party like the posts of various media organizations that broadcast statements and interviews of the candidates. The former does it more than 6% of the times and the latter almost 5% of the times. Besides, the Socialist Party likes the posts of an organization account and an opinion leader outside its ranks.

Both @pparagon and @aragonpsoe like more times the same accounts they usually retweet. The Popular Party does it with @Jorge_Azcon (more than 44%), @ChuecaNatalia (more than 13%) and there is a tie between @ppopular and @NunezFeijoo -Popular Party candidate for 2023 general elections- (more than 10%). PSOE does it with @JLambanM (almost 69%), @zaragozapsoe (almost 8%) and @PSOE (more than 6%). While the Popular Party interacts in this way with 22 unique accounts (almost 13% of the total), the Socialist Party interacts with 12 (almost 19%). Only the Socialist Party likes profiles outside its ranks on 3 occasions.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

After analyzing and comparing the use of Twitter in the campaign for 2023 autonomic elections by @pparagon and @aragonpsoe, following the research objectives and contrasting their hypotheses, the authors present the following conclusions.

First, regarding H1, it is true that the two parties spread a large amount of content throughout the campaign period. Although PSOE’s numbers are much higher, this is the most active period of both parties’ profiles in the year, as assured by Alonso et al. (2016). However, to state that the number of posts increases as election day approaches is not totally accurate. It happens in the case of the Socialist Party, but not with the Popular Party, whose activity increases during the first week, but decreases on the second week, when voting day is closer. On the other hand, it is true that both parties respect day-before-election silence and that there is little activity on the day after elections.

The authors conclude the Popular Party seems to have a more spontaneous posting frequency, whereas the Socialists present a strategy more guided towards specific schedules and content. This proves that all Twitter posts have been previously prepared, although there are peaks of activity at specific times -rallies, media appearances, visits by party members, etc.-, despite the advantages of the platform for sending and receiving all kinds of real-time information (Alonso et al., 2021).

Regarding H2, the authors confirmed that the vast majority of tweets are used to showcase both parties’ electoral events, as assured by Sabés and Zugasti (2015). Thus, they prioritize the presentation and promotion of their campaign messages and agendas and their appearances in the media, interviews or debates in the form of self-reference and self-propaganda, to praise the image of the party and the regional and municipal candidates. PSOE does it more often, posting on daily basis. Likewise, the authors corroborated the common use of criticisms and negative comments towards other parties and their leaders, attacking and undermining their image, as Mancera and Pano (2014) pointed out. They observed this practice is more frequent in the case of the Popular Party, something rather common considering it is the main opposition party.

Similarly, the authors found that both the Popular Party and the Socialists use Twitter to mobilize their constituents, requesting their vote directly through emotional strategies that bring parties’ representatives closer to the public and presenting their achievements in an attractive fashion. In this sense, both parties remain on the same line Pano (2020) detected in the previous electoral cycle. The authors also verified that, although to a lesser degree, the parties use the microblogging network in an informative way, presenting their proposals and other issues of interest. The authors also corroborated the fact that neither party uses Twitter to establish a direct communication with their voters’ community.

Regarding H3, the authors found that @aragonpsoe and @pparagon both have personalized online communication strategies, but they exploit Twitter’s potential in a very different way. Firstly, the number of shares throughout the period studied is much higher in the case of the Socialist Party. On the other hand, while most of the publications of this party are original (tweets and comments), this premise is not fulfilled in the case of the Popular Party, which uses more retweets and likes to posts shared by other users.

The data show that when it comes to developing a structure for posts, PSOE's strategies are more original and creative. The two profiles incorporate various elements in the vast majority of their posts -as Gamir (2016) said-, the Popular Party however is much less likely to use them. Although the Socialist Party surpasses the Popular Party in their use, they both employ and combine the following components: texts of different sizes, audiovisual elements in the form of images and videos, hashtags, mentions and hypertexts such as links and buttons.

Regarding H4, the authors corroborated that the parties do not establish a horizontal dialogue with their voters. Some authors have stated that this platform serves as a direct communication and interaction channel between politicians and citizens (García and Zugasti, 2016). However, the authors of the present research have observed that parties do not use comments, mentions and hypertexts -all proper elements for a horizontal communication- to engage in conversations with citizens, but rather employ those tools with a self-referential purpose. In short, the authors’ findings coincide with those of Ramos-Serrano et al. (2018), who found that Twitter debate during 2014 European elections took place only among political representatives. This reality affects not only social networks, but also the parties' web spaces, where the possibilities of interaction between users and political organizations are minimal (García and Abuín, 2019). The authors also agree with the fact that the growing polarization detected in studies such as Donstrup's (2020) may be the reason that dissuades political parties from communicating directly with users.

Something similar happens with other people's posts, since both @aragonpsoe and @pparagon retweet and like only profiles and posts directly related to them. They almost never use these functions to amplify information that is not part of their campaign and in no case do they do so with their voters. As in the case of Mancera and Pano's research a decade ago (2013), the Socialist Party and the Popular Party share content published by their representatives, by other groups of the same party and by the media -only when their candidates appear and show a good image, or when their opponents are criticized-.

Chart 1

Summary of the main results obtained in the research.

|

|

PSOE Aragon |

PP Aragon |

|

Amount of posts |

551 |

442 |

|

Posts average |

30 / day |

24 / day |

|

Main theme of tweets |

Campaign event (74%) |

Campaign event (42%) |

|

2nd main topic of tweets |

Own achievements (6.5%) |

Criticism of the opponent (28%) |

|

Most common type of publication |

Tweets (44%) |

Retweets (44%) |

|

2nd Type of publication |

Comments (33%) |

Likes (39) |

|

Use of text in tweets |

99% |

100% |

|

Use of audiovisual in tweets |

94% |

86% |

|

Use of hashtags in tweets |

82% |

68% |

|

Use of mentions in tweets |

84% |

38% |

|

Use of hypertexts in tweets |

26% |

9% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Social networks have indeed become a crucial element in the strategy of any political campaign (Calvo et al., 2019) as there is a growing personalized use of Twitter’s different elements of (Díaz et al., 2016). However, those in charge of political communication do not fully exploit its potential (Moreno and Castillero, 2023; Peris et al., 2020), even though they are aware of it, as demonstrated along the present study.

Though mainly limited by its focus on a specific channel, period and political parties, this research can serve as the basis for future studies related to online political communication. For example, it allows to contrast the development of political parties, other communities, parties at a national level, and to compare different periods, etc. All those elements may constitute the foundations for the study of online campaign strategies or the analysis of the necessary communication strategies to improve horizontal interaction patterns on social networks.

6. REFERENCES

Abejón, P., Linares, V. y Sastre, A. (2012). Facebook y Twitter en campañas electorales en España. Disertaciones: Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social, 5(1), 129-159. https://revistas.urosario.edu.co/index.php/disertaciones/article/view/3887

Alonso Muñoz, L., Casero Ripollés, A. y Miquel Segarra, S. (2016). Un potencial comunicativo desaprovechado. Twitter como mecanismo generador de diálogo en campaña electoral. Obra digital, 11, 39-59. https://doi.org/10.25029/od.2016.100.11

Alonso Muñoz, L., López Meri, A. y Marcos García, S. (2021). Campañas electorales y Twitter. La difusión de contenidos mediáticos en el entorno digital. Cuadernos.info, 48, 27-47. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.48.27679

Alonso Muñoz, L., Marcos García, S. y Miquel Segarra, S. (2017). Buscando la interacción. Partidos y candidatos en Twitter durante las elecciones generales de 2015. Prisma Social, 18, 34-54. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/1353/1656

Argilés Martínez, L., Cano Orón, L. y López García, G. (2016). Circulación de los mensajes y establecimiento de la agenda en Twitter: el caso de las elecciones autonómicas de 2015 en la Comunidad Valenciana. Trípodos, 39, 163-183. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Tripodos/article/view/335042/425708.

Berzosa Moreno, A., Marín Dueñas, P. P. y Simancas González, E. (2019). Uso e influencia de Twitter en la comunicación política: el caso del Partido Popular y Podemos en las elecciones generales de 2016. Cuadernos.info, 45, 129-144. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.45.1595

Bustos Díaz, J. y Ruiz del Olmo, F. J. (2016). La imagen en Twitter como nuevo eje de la comunicación política. Opción, 32(7), 271-290. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5916872

Calvo Miguel, D. y Campos Domínguez. (2017). La campaña electoral en Internet: planificación, repercusión y viralización en Twitter durante las elecciones españolas de 2015. Comunicación y sociedad, 29, 93-116. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=34650597006

Calvo Miguel, D., Campos Domínguez, E. M. y Díez Garrido, M. (2019). Hacia una campaña computacional: herramientas y estrategias online en las elecciones españolas. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 51, 123-154. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.51.05

Calvo Rubio, L. M. (2017). El uso de Twitter por los partidos políticos durante la campaña del 20D. Sphera Publica, 1(17), 111-131. https://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/304

Caldevilla Domínguez, D. (2009). Democracia 2.0: La política se introduce en las redes sociales. Pensar la publicidad, 3(2), 31-48. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PEPU/article/view/PEPU0909220031A

Capdevila Gómez, A. y Machado Flores, N. (2017). Los issues del PSOE y Podemos en Twitter durante la campaña electoral de mayo de 2015 en España. Comunicación y hombre,13, 103-132. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=129449617006

Casero Ripollés, A. y Rúas Araújo, X. (2018). Comunicación política en la época de las redes sociales: lo viejo y lo nuevo, y más allá. adComunica, 16, 21-24. https://acortar.link/fdJiyj

Casero Ripollés, A., López Meri, A. y Marcos García, S. (2017). ¿Qué hacen los políticos en Twitter? Funciones y estrategias comunicativas en la campaña electoral española de 2016. El Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 795-804. https://acortar.link/OdNLxH

Cervi, L. y Roca, N. (2017). Cap a l’americanització de les campanyes electorals? L’ús de Facebook i Twitter a Espanya, Estats Units i Noruega. Anàlisi. Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 56, 87-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3072.

Congosto, M. L. (2015). Elecciones Europeas 2014: Viralidad de los mensajes en Twitter. Redes. Revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales, 26(1), 23-52. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/931/93138738002.pdf.

de Sola Pueyo, J. (2020). La ciencia y las oenegés, en un segundo plano frente a la política y Greta Thunberg: los protagonistas de la Cumbre del Clima de Madrid según la radio española. Zer, 25(48), 147-163. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.21412

de Sola Pueyo, J., Nogales Bocio, A. I. y Segura Anaya, A. (2021). Nuevas formas de comunicación de la radio: la investidura de Pedro Sánchez 'radiada' en Instagram. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 12(1), 129-141. https://www.doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM000017

Díaz Campo, J., Lloves Sobrado, B. y Segado-Boj, F. (2016). Objetivos y estrategias de los políticos españoles en Twitter. index.comunicación, 6(1), 77-98. https://acortar.link/kXTa8q

Díaz Guerra, A. y Marín Dueñas, P. P. (2016). Uso de Twitter por los partidos y candidatos políticos en las elecciones autonómicas de Madrid 2015. Ámbitos, 32, 1-15. https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/66527

Donstrup, M. (2019). Propaganda en redes sociales: Análisis de contenido en Twitter durante la campaña electoral andaluza. Obra digital, 17, 63-76. https://doi.org/10.25029/od.2019.243.17

Donstrup, M. (2020). ’Al menos nos hemos divertido’: respuestas en Twitter al debate electoral 4N. Vivat Academia, 152, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2020.152.1-18

Equipo Piedras de papel (2015). Aragón es nuestro Ohio: Así votan los españoles. Editorial El hombre del tres.

Gamir Ríos, J. (2016). Blogs, Facebook y Twitter en las Elecciones Generales de 2011. Estudio cuantitativo del uso de la web 2.0 por parte de los cabezas de lista del PP y del PSOE. Dígitos, 2, 101-120. https://revistadigitos.com/index.php/digitos/article/view/53/23

García Gordillo, M., y Pérez Curiel, C. (2020a). Del debate electoral en TV al ciberdebate en Twitter. Encuadres de influencia en las elecciones generales en España (28A). El Profesional de la información, 29(4), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.jul.05

García Gordillo, M. y Pérez Curiel, C. (2020b). Indicadores de influencia de los políticos españoles en Twitter. Un análisis en el marco de las elecciones en Cataluña. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 26(3), 1133-1144. https://doi.org/10.5209/esmp.64880

García Ortega, C. y Zugasti Azagra, R. (2016). Los temas de campaña en Twitter: caso de los candidatos a la Presidencia de Aragón en 2015. Revista F@ro, 1(23), 181-194. https://www.revistafaro.cl/index.php/Faro/article/view/465/354.

García Ortega, C. y Zugasti Azagra, R. (2018). Gestión de la campaña de las elecciones generales de 2016 en las cuentas de Twitter de los candidatos: entre la autorreferencialidad y la hibridación mediática. El Profesional de la Información, 27(6), 1215-1224. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.nov.05

García Rosales, D. F. y Abuín-Vences, N. (2019). The use of hypertextuality, multimedia, interactivity and updating on the websites of Spanish political parties. Communication & Society, 32(1), 351-367. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.37837

Gelado Marcos, R., Navío Navarro, M. y Rubira García, R. (2019). Comunicando en los nuevos entornos. El impacto de Twitter en la comunicación política española. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 10(2), 73-84. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2019.10.2.11

Guerrero Solé, F. y Mas Manchón, L. (2017). Estructura de los tweets políticos durante las campañas electorales de 2015 y 2016 en España. El Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 805-815. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.03

Herrera Damas, D. S. y Moya Sánchez, M. (2015). Cómo puede contribuir Twitter a una comunicación política más avanzada. Arbor, 191(774). http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2015.774n4012.

López García, G. (2016). Nuevos y viejos liderazgos: la campaña de las elecciones generales españolas de 2015 en Twitter. Communication & society, 29(3), 149-168. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.29.35829

Mancera Rueda, A. y Pano Alamán, A. (2013). Nuevas dinámicas discursivas en la comunicación política en Twitter. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, 56, 53-80. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_CLAC.2013.v56.43867

Mancera Rueda, A. y Pano Alamán, A. (2014). La “conversación” en Twitter: las unidades discursivas y el uso de marcadores interactivos en los intercambios con parlamentarios españoles en esta red social. Estudios de lingüística del español, 35, 234-268. https://raco.cat/index.php/Elies/article/view/285730

Moreno Cabanillas, A. y Castillero Ostio, E. (2023). Comunicación política y redes sociales: análisis de la comunicación en Instagram de la campaña electoral del 13F. Vivat Academia, 156, 199-222. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2023.156.e1461

Pano Alamán, A. (2020). La política del hashtag en Twitter. Vivat Academia, 152, 49-68. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2020.152.49-68

Pérez González, J. y Zugasti Azagra, R. (2015). La interacción política en Twitter: el caso de @ppopular y @ahorapodemos durante la campaña para las Elecciones Europeas de 2014. Ámbitos, 28, 1-14. https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/66536.

Peris Blanes, Á., López García, G., Cano Orón, L. y Fenoll, V. (2020). Mediatización y mítines durante la campaña a las elecciones autonómicas valencianas de 2019: entre la «lógica mediática» y la «lógica política». Debats, 134(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.28939/iam.debats.134-1.4

Ramos-Serrano, M., Fernández Gómez, J. D. y Pineda, A. (2018). Follow the closing of the campaign on streaming: The use of Twitter by Spanish political parties during the 2014 European elections. New Media & Society, 20(1), 122-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660730

Renobell, V. (2021). Análisis del discurso político en Twitter en España: el caso de las elecciones generales de abril de 2019. Revista de Estudios Políticos, 194, 283-302. https://doi.org/10.18042/cepc/rep.194.10

Sabés Turno, F. y Zugasti Azagra, R. (2015). Los issues de los candidatos en Twitter durante la campaña de las elecciones generales de 2011. Zer, 20(38), 1137-1102. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.14792

Sánchez Aranda, J. J. (2005). Análisis de contenido cuantitativo de medios. En M. R. Berganza Conde y J. A. Ruiz San Román, Investigar en comunicación: guía práctica de métodos y técnicas de investigación social en comunicación (pp. 207-228). McGraw-Hill.

Suau Gomilla, G. (2020). Microblogging electoral: la estrategia comunicativa de Podemos y Ciudadanos en Twitter en las campañas electorales del 20D y el 26J. Prisma Social, 28, 103-126. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3389

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: De Sola Pueyo, Javier and Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Methodology: De Sola Pueyo, Javier and Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Software: Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Validation: De Sola Pueyo, Javier and Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Formal analysis: De Sola Pueyo, Javier and Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Data curation: Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Drafting-Revision and Editing: De Sola Pueyo, Javier. Visualization: Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. Supervision: De Sola Pueyo, Javier. Project management: De Sola Pueyo, Javier and Pascual Santisteve, Ainara. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: De Sola Pueyo, Javier and Pascual Santisteve, Ainara.

Funding: This research did not receive external funding.

AUTHORS:

Javier de Sola Pueyo: PhD in Communication, Master in Marketing and Corporate Communication and Bachelor in Journalism. Currently, professor of Journalism at the University of Zaragoza, where he has been teaching since the 2016/2017 academic year. Member of the Research Group in Communication and Digital Information(GICID). His research is mainly focused on the study of the radio media and journalistic coverage of current affairs, especially in relation to politics and climate change.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3006-8236

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=Mp54gtIAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Javier_De_Sola

Academia.edu: https://ieiop.academia.edu/JavierdeSolaPueyo

Ainara Pascual Santisteve: Master's Degree in Information and Digital Communication Consulting and Bachelor's Degree in Journalism. Currently, she is expanding her training with a Master in Communication, Culture, Society and Politics at the National University of Distance Education (UNED). Her work focuses mainly on the mediatization of politics, the communication strategies of political actors in the network and the study of political cultures.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3884-782X

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ainara-Pascual-Santisteve

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/AinaraPascual