doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.154.e1384

RESEARCH

FROM OCCUPATION TO COVID, PASSING THROUGH THE M.E.N.A.S. SEMIPRESENTIAL DIALOGUE AS AN INNOVATIVE METHODOLOGY OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL LEARNING

DE LA OCUPACIÓN AL COVID, PASANDO POR LOS M.E.N.A.S. EL DIÁLOGO SEMIPRESENCIAL COMO METODOLOGÍA INNOVADORA DE APRENDIZAJE ANTROPOLÓGICO

DA OCUPAÇÃO À COVID, PASSANDO PELAS MENAS. DIÁLOGO SEMIPRESENCIAL COMO METODOLOGIA INOVADORA DE APRENDIZAGEM ANTROPOLÓGICA

María Isabel Ralero Rojas1

1University of Castilla-La Mancha. Spain

ABSTRACT

The dialogical method as a mixed technique of anthropological research and learning can have a very promising development inside and outside the classroom. This implies assuming that the role of the students can be equated with that of the subjects who construct the social reality where our objects-subjects of study are located, and that from this role they can become important sources of reflexivity to delve into the analysis of relevant social facts. in the present moment. Introducing tools in classrooms that allow deconstructing certain realities based on the students' own discourses greatly facilitates their questioning, even more so if we take into account that these future professionals in the social field will carry out their work in complex societies where dialogue seems fundamental to reach a true understanding of this complexity. In the context of the current health crisis, in addition, virtual spaces and blendedness have brought new challenges but also new opportunities with which to enrich learning processes. With this work we will be able to see, through the students' own literality, how through a blended discussion group it is possible to construct key anthropological questions based on the group's own interests, reaching in a single session important transversal and specific curricular learning of the mattery. This can contribute to a better understanding of the teaching role as companions in this construction, so that it is possible to attend to the diversity of approaches and positions existing inside and outside the classroom.

KEYWORDS: discussion groups, dialogic learning, qualitative research, anthropological teaching, blendedness, virtuality, occupation, Covid, unaccompanied foreign minors

RESUMEN

El método dialógico como técnica mixta de investigación y aprendizaje tiene un desarrollo muy prometedor dentro y fuera de las aulas. Ello supone asumir que el papel del alumnado puede equipararse al de los sujetos que construyen la realidad social donde se ubican nuestros objetos-sujetos de estudio, y que desde ese rol pueden convertirse en importantes fuentes de reflexividad para adentrarnos en el análisis de hechos sociales relevantes en el momento actual. Introducir en las aulas herramientas que permitan deconstruir determinadas realidades a partir de los propios discursos de las y los estudiantes, facilita en gran medida su cuestionamiento, más aún si tenemos en cuenta que estos futuros profesionales del ámbito social desempeñarán su trabajo en sociedades complejas en donde el diálogo sumergido en la diversidad puede ser clave para alcanzar una verdadera comprensión de dicha complejidad. En el contexto de crisis sanitaria actual, además, los espacios virtuales y la semipresencialidad han supuesto nuevos retos pero también nuevas oportunidades con las que enriquecer los procesos educativos. Con este trabajo comprobaremos, a través de la propia literalidad del alumnado, cómo desde un grupo de discusión semipresencial se pueden construir cuestiones clave antropológicas basadas en los propios intereses del grupo, alcanzando en una sola sesión importantes aprendizajes curriculares tanto transversales como específicos de la materia. Esto puede contribuir a entender mejor el papel docente como acompañante en esta construcción, de manera que sea posible atender a diversidad de planteamientos y posiciones existentes dentro y fuera del aula.

PALABRAS CLAVE: grupos de discusión, aprendizaje dialógico, investigación cualitativa, docencia antropológica, semipresencialidad, virtualidad, ocupación, Covid, menas (menores extranjeros no acompañados)

RESUMO

O método dialógico como técnica mista de pesquisa e aprendizagem tem um desenvolvimento muito promissor dentro e fora da sala de aula. Isso implica assumir que o papel dos alunos pode ser equiparado ao dos sujeitos que constroem a realidade social onde nossos objetos-sujeitos de estudo estão localizados, e que a partir desse papel eles podem se tornar importantes fontes de reflexividade para aprofundar a análise de fatos sociais relevantes.A introdução de ferramentas nas salas de aula que permitam desconstruir certas realidades dos discursos dos próprios alunos facilita muito seus questionamentos, ainda mais se levarmos em conta que esses futuros profissionais da área social farão seu trabalho em sociedades complexas onde o diálogo imerso na diversidade pode ser a chave para alcançar uma verdadeira compreensão desta complexidade. Além disso, no contexto da atual crise de saúde, os espaços virtuais e a integração trouxeram novos desafios, mas também novas oportunidades para enriquecer os processos educativos. Com este trabalho verificaremos, através da própria literalidade dos alunos, como a partir de um grupo de discussão misto é possível construir questões antropológicas fundamentais a partir dos próprios interesses do grupo, alcançando em uma única sessão importantes aprendizagens curriculares, transversais e específicas aos assuntos. Isso pode contribuir para uma melhor compreensão do papel do professor como companheiro dessa construção, de modo que seja possível atender à diversidade de abordagens e posicionamentos existentes dentro e fora da sala de aula.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: grupos de discussão, aprendizagem dialógica, pesquisa qualitativa, ensino antropológico, blendedness, virtualidade, ocupação, Covid, menas (menores estrangeiros não acompanhados)

Correspondence

María Isabel Ralero Rojas. University of Castilla-La Mancha. Spain mariaIsabel.Ralero@uclm.es

Recibido: 10/05/2021

Aceptado: 13/09/2021

Publicado: 03/01/2022

Cómo citar el artículo

Ralero Rojas, M-I. (2022). From Occupation To Covid, Passing Through The M.E.N.A.S. Semipresential Dialogue As An Innovative Methodology Of Anthropological Learning. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 155, 197-217. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.154.e1384

Translation by Paula González (Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Venezuela)

1. INTRODUCTION

Covid has broken into classrooms with some changes and measures to guarantee the health of teachers and students, which, in principle, have caused a significant imbalance in terms of didactic programming and the methodology with which to achieve the curricular objectives. It has also meant greater use of virtuality as a learning space and an adaptation of content to the use of these tools. This new context of the educational environment, where semi-presentiality [1] generates important challenges to advance not only in the presentation of content by teachers but also in the participation of students in their own educational processes, has instead allowed us to reflect on how to connect what is outside with what is inside, what happens inside the classroom with what happens beyond the classic learning environment.

And this new reflective framework enables us to explore new educational formulas that involve important role changes in the knowledge construction process. We could, instead, think from these approaches imposed by the health situation, which to a certain extent alienate students, that it is now less likely than before to move towards dialogical learning of any subject. In this sense, the Dialogic Learning Theory (Flecha, 1997) clarifies that learning depends on interactions and not so much on processes generated from individuality, so we have in our classrooms the most important tool to guarantee educational quality: the group itself. Thus, if the group is divided into two different contexts, the face-to-face and the non-face-to-face, we must try to combine both in the most productive way possible: through the assignment of different roles in the collective knowledge construction. Besides, from this framework, the concepts of instrumental and communicative action are useful to identify two types of relationships that play a fundamental role in education, those of power and dialogic (Duque and Prieto, 2009: 11), where dialogue-based participatory tools imply the application of a more egalitarian logic of connection of different positions where learning can be made more diverse and more effective.

[1] We are going to define this concept as a mixed workspace, which combines face-to-face moments in the classroom with others where participation in educational dialogic activities occurs from home.

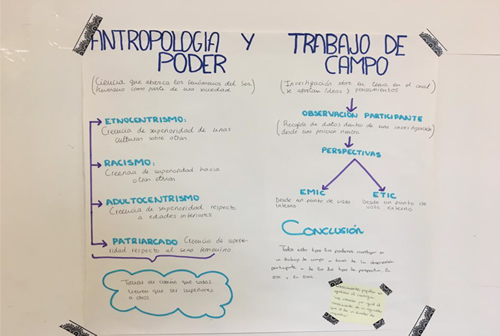

Image 1. Face-to-face dialogic construction of anthropological concepts in the Degree in Social Work. 2019-2020 academic year (first semester)

This work aims to reflect on both relationships in this new blended environment that appears in the 2020-21 academic year, from the analysis of a concrete learning process carried out through the discussion group technique, observing how connecting this new context with some fundamental anthropological content for the vehicular understanding of the subject, these contexts can become key factors for learning. This is understood from the didactic exercise of a dialogic-critical Anthropology, where a more active position of social actors in research and knowledge production is appreciated, it is not unilateral, but in collaboration (Hernández Espinosa, 2007: 321). This may contain a strong applied dimension because, if we conclude that the established dialectic allows the flow of ideas and thoughts, enabling changes or improvements in these perceptions, we could propose proposals that use these dialogic techniques as a sensitizing and social transformation methodology with the groups involved. This may be especially relevant if we take into account the relationship of tools based on PAR (Participatory Action Research) as ethnographic methodologies that provide us with an epistemologically superior opportunity than conventional research since their collaborative action brings together entire lives of local and professional knowledge (Greenwood, 2000: 47) and build a depth of what has been learned greater than that carried out from an approach more focused on the researcher as a position of power that limits and imposes its own scientific-conceptual order.

It is also important to conceptually define the blended dialogue as an encounter with the other - one with whom the same physical space is not shared - that allows a creative construction of knowledge. Dialogical communication where intercultural dialogue also takes place and enables participants in one more environment to meet and dialogue with the other wherever they are, allowing this dialogue relationship to lead us to the recognition of the incomplete and finite nature of our cultural understandings of the world. Therefore, there will be no intercultural dialogue if there is not a critical distancing from the particular vision of one's own culture first: self-reflection of one's own as a starting point for the appreciation of what is foreign (Uribe Sánchez, 2014).

To carry out this analysis that methodologically combines the discussion group, dialectical learning, and Participatory Action Research, we will use the speeches generated in a class of Anthropology of the first year of Social Work of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Talavera de la Reina of UCLM, through a discussion group made up of two environments: one in the classroom and the other from home. The one in the classroom was freely chosen by 8 participating students, two facilitators, and two reporters of conclusions, the rest of the students present adopting a role of external observers with the option to promptly intervene during the development of the dynamics, and especially to provide their view after its completion, the next day. The students who were from home followed the class through the Teams platform, facilitating their participation in the group through the written chat. The teaching role, in this case, was only exercised from the facilitation of the information that was generated when the connection or understanding failed in both spaces, virtual and face-to-face. Thus, they took care of transferring the topics and some speeches expressed in the face-to-face group to this forum, to ensure different ways of constructing opinions between the students present in the classroom and those who followed the class from outside. The group's operating dynamics were open. Three topics were proposed to choose from: the occupation of homes, the social and political debate generated around unaccompanied foreign minors, and, lastly, the social impact of Covid-19. After counting the people in favor of each topic, a student of the face-to-face modality noticed that with the third one they could all be addressed because, in this context, these issues had become more acute. The face-to-face group -because the non-face-to-face group did not take sides in this decision- then agreed to start the debate broadly, trying to address everything, if possible. In this way, the interests of the students were allowed to give shape and different times to the proposed topics.

2. OBJECTIVES

With these objectives, we will be able to assess to what extent the blended dialogue generated with two different groups (face-to-face in the classroom and not face-to-face from home) can be useful for the anthropological construction of knowledge, especially from its EMIC perspective (internal view of the group itself) and ETIC (external view). Also, if under this modality the application of dialogic participatory didactics is still possible and/or desirable, and, finally, if what was observed in the development of this specific analysis could be useful to advance more towards the dialogue construction of new innovative teaching methodologies of blended action-research, which would undoubtedly allow greater involvement of social actors in processes of social transformation.

3. METHODOLOGY: DISCUSSION GROUPS AS KNOWLEDGE-BUILDING TOOLS

Although there are different ways to conceive and materialize a discussion group depending on the discipline and/or professionals who put it into practice, we are starting from a broad definition that allows us to focus on the generated dialogue above its application guidelines. As we move, in this case, through an experience constructed and analyzed from anthropological didactics, we are especially interested in the action of the students to construct their own discourse based on what another subject who is inside or outside the classroom says, and therefore, sharing or not different contexts of participation. Thus, in one way or another, the confrontation of points of view between the participants in a discussion group allows them to form and specify their positions or evolve in their approaches (Gil, 1993: 210), making it possible to build shared and not shared meanings and senses in that mixed space constituted by semi-presentiality. In this way, through socialized conversation, speech, and reflection, the meaning and significance of the topic were found and symbolic or imaginary social universes were built and legitimized (Arboleda, 2008: 72).

Although discussion groups are a qualitative technique widely used in areas such as Sociology and Social Anthropology, discussion or dialogue helps us to obtain meaningful information about this symbolic universe that makes “people think or feel the way they do" (Krueger, 1991: 22, cited by Porto and Ruiz, 2014: 253). We, therefore, understand the discussion group as a qualitative technique/practice from which a discursive raw material is obtained, whose analysis will serve to give an account of the collective representations and images, as well as the group structures that are articulated around a significant or/and specific problem under study (Montañez, 2010: 2). This technique allows establishing a dialogue, in this case between participating students, while constructing a group discourse, rich in codes, expressions, opinions, and silences, which allows a display of speech and voices and generates a stimulus for the creation of meanings and senses (López Francés, 2010: 148).

Image 2. Dialogic diagrams that were carried out by face-to-face students on the concept of estrangement and cultural distancing

This consideration of the discussion group as a dialogic learning tool, as well as a qualitative research instrument that allows access to these collective representations significant for the current context, invites us to reflect on its use and connection with new educational formulas, such as semi-presentiality, through the use of virtual platforms. This suggests new exploratory paths for blended learning -between face-to-face and virtual-, if we modify the role of students from passive reception to the active construction of content linked to their perceptions of their own lived social context.

This experience must also be contextualized within a computer-mediated collaborative/cooperative learning referred to online learning, capable of using the different modalities -face-to-face, non-face-to-face, and blended- and that uses cooperative and/or collaborative learning as a teaching method (Salmerón, Rodríguez, & Gutiérrez, 2010: 165). From the dialogic construction of this social knowledge, we observe the method itself as a research possibility (Muñoz, 2013: 2), with interdisciplinary implications in many other fields necessary for the holistic dimension of Anthropology.

In the specific context of the formal teaching of a subject such as Social and Cultural Anthropology, it is important to attend to the students' own knowledge and experience as a representative subject of the predominant images in different socio-cultural contexts: young people from rural or urban areas, of internal or international migrations, belonging to majorities or different ethnic or religious minorities. People crossed, like all, by gender roles, age, social class. Carriers of prejudices and stereotypes of their own and others. Of collective identities or private and shared senses of belonging. Users, participants, citizens of a globalized world. Voters and supporters. Neighbors. Future workers in the public and/or private sphere. With this diversity existing in the classroom, it is inevitable to count on it for the collective reflection of all those great anthropological issues: we have, within our group, learners with a significant number of positions, meanings, and categories experienced in the first person from which to start, exercising our own and others estrangement, to come to understand the complexity of our current societies. And this privileged place is multiplied if it is related to the construction of dialogical learning.

4. RESULTS. THE VALIDITY OF BLENDED DIALOGUE FOR BUILDING ANTHROPOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE

4.1. The dialogical as an ethnographic source from where to build the unexpected

On many occasions, the most relevant aspects of our anthropological fieldwork appear in informal conversations or unexpected encounters. Thus, just as we assume that the quality of our research does not depend so much on our own individual intellectual work as on our ability to interact and awaken reflexivity together with the subjects we interact with, we must think that something similar happens when we are in an educational space in where our role is to facilitate access to knowledge –in the case at hand, also anthropological-. This means admitting that, in the teaching field, we not only transmit it, we also build it regarding our relationship with the students. In this way, through a dialogue between equals that allows us to start from their own perceptions and images on certain topics relevant to the socio-anthropological analysis of current reality, we can move towards the acquisition of shared learning that allows us to move beyond the field of the social representations that we have in the classroom, the analysis of the syllabus, and the achievement of the curricular objectives.

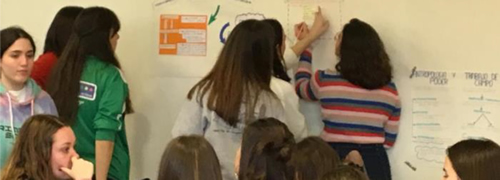

Image 3. Dialectical construction of anthropology terminology in classroom mode

From this position, the discussion group serves us in the same way as the debate, the research work by cooperative groups than the generating questions thrown in the middle of a class. The important thing lies in the search for group knowledge towards learning to be discovered after different collective contributions are produced in the classroom. In this sense, despite the changes that the health crisis may have generated in the forms of relationships or the generalized emergence of virtual environments, we can think that the important thing will be not to lose ourselves in these forms, but to advance in maintaining or improving our objectives through them. This implies having to integrate into the already broad world of human relations one more context from which to continue advancing for the collective construction of knowledge. Doing so can be an interesting challenge that leads to innovative responses.

In the work at hand, we are going to describe a concrete process through group construction to later draw some important conclusions about the way to dialogically integrate into educational settings concepts such as semi-presentiality, virtuality, socio-anthropological analysis of key categories such as social class, individuality or collectivity, marginality and inequality, processes of social exclusion, and diversity.

4.2. Development of the discussion: dialogical learning and construction of anthropological knowledge

The discussion began with the issue of occupation, launched by a student who positioned himself "in favor", starting with a certain ethical stance in the speeches. The participants began to debate about the legitimacy of the act itself, trying to define the social responsibility of occupation: if it is a public or private issue, if it has to be approached from the individuality of each case or with a broader perspective that the group defined as social and, therefore, if it required certain norms or collective regulation. From this consideration as a social fact, on the other hand, it was necessary to attend to the particular characteristics of each occupation situation, the legal and administrative framework where it can be defined as a crime, and how its simplification allows it to be politically used to legitimize the very mechanisms of inequality. In any case, a great consensus was generated in placing occupation as a practice that arises from the lack of response of the state to the lack of housing, although this need was also defined as a fundamental basic right:

Later, in the discussion, an interesting debate began where different positions were assigned to the fact of occupying: as a consequence of the lack of the necessary means to access a normalized house or as a criminal act carried out by illegal networks where the occupies turn into a victim position. In any case, after some debate regarding these two defining situations, the concept of necessity tended to be more clearly linked to that of occupation. But by doing so, other actors who benefit from this situation from more illegal and immoral positions, and who ultimately for the group would be causing a simplification of ideas in the collective imagination and a direct association between criminal activity and occupation, came onto the scene. The way how this dialogued dialectic was produced provides many keys in this regard, introducing those illegal intermediary figures (the mafias), along with the lack of clear and effective legislation that better defines the concept of need, taking into account variables such as urgency and the scarcity of existing means to provide answers:

The discussion continued by introducing key components that can define the phenomenon: social class and its possible relationship with the most vulnerable or disadvantaged neighborhoods or areas. As indicated by the participating students, it seems that certain practices could go more easily through some spaces than others and that certain prejudices operate in public opinion to generate some confusion between concepts that, without being the same or having the same legal considerations, comply with an important function in the collective beliefs that make occupation a possibility to be feared by anyone. Especially interesting was the contribution of a student (B) on the symbolic processes of identification of certain neighborhoods with criminal practices, and how this may be influencing the formation of images that favor occupation:

Through the participation of the students from home, important considerations not present in the face-to-face debate were added, in whose group there was quite a homogeneity in the approaches. For example, in how we define occupation (introduced by student D), to what extent it has been amplified in this Covid- context as an aggravating factor of social inequality, and if the way to solve homelessness should be produced outside the system, with transgressive solutions that, as stated, do not allow situations of inequality to change either. These insights, which were generated from home, were important for the global analysis of the phenomenon since, although in a majority way it was seen as something legitimate that “a family without access to a standardized home occupies a house”, they did not want to lose sight that placing a family outside the system has repercussions and may aggravate their situation of vulnerability. At the same time, the difference between the occupation of banks’ houses and private homes was exposed, as well as their different uses -if it is a way of life, a home, an economic asset, or a place of residence-, particularities or nuances that are important when it comes to differentiating what is shown to us from the narratives of power as a homogeneous and distorted reality, from the fear of the middle class to be occupied and that their economic promotion efforts through the social fabric are depleted:

After having reached a certain consensus on the phenomenon of occupation, the face-to-face group considered the issue done and began to broaden the analysis to other structures of social inequality, introducing the issue of unaccompanied minors and the need for more support to all these groups so that they can solve complex situations. Part of the students highlighted the current increase in processes of incitement to hatred towards certain groups in a clearly socially disadvantaged situation, as well as greater current permissiveness towards these logics. In some cases, it was observed how in a context of socio-sanitary crisis, competitiveness increases and with it the need to blame the “other”, whether it is someone who occupies a house, a foreigner, or an m.e.n.a, generating mechanisms or narratives that exclude and legitimize positions of inequality around these categories:

[Teacher's note. At this time, some members of the group begin to ask specific questions directed to a participant, to find out how she would do it. She seems to have some consideration for the class. For J the problem is "such individualistic society"]:

Based on this approach based on the interaction between the individual and the collective, how educational or family models may or may not reproduce the social inequality of certain groups was included in the analysis. In this way, the dialogue generated in the face-to-face group tended towards a shared and predominant position where beliefs and knowledge, positions, and social practices were relativized according to the context in which the main individual and collective learning were generated. Thus, a predominance of positions that moved in a certain social determinism was reached where the agents seem to have little margin for mobility, innovation, or change. However, from non-face-to-face students, more dynamic positions were raised where changes were possible:

M: "Everyone knows things their way, depending on where you grew up... On the education you received... Here because we are studying what we are studying... But... sometimes you can study whatever, they are guided more by what parents say [It seems that for this student family education "is not a viable way out", because in the family, “how you relate to your parents and siblings, and how they do with others, makes us the way we are”, social inequality is reproduced]

At this point in the discussion, the face-to-face group reaches a certain tendency to determinism, assessing the existing difficulty in social transformation based on individual or collective options; At this time, other voices (with the role of observers in the face-to-face mode) that had not yet joined the discussion, asked to do so and very briefly raised other approaches or views in which other actors intervene. This intervention allowed participants who had apparently reached dead-end positions to generate different educational, emotional, and individual responses with which the collective could be transformed. In this way, the boundaries between the individual and the collective are blurred, observing that the structures of inequality can also be related to the strategies with which people build their own will for change. From home, after raising the existing difficulties for social change following educational channels, the idea of revolution emerged as the only real way of transformation:

S: "It is not only what Mom or Dad tell me, but there are also many people influencing"

The latest contributions from participants from both the face-to-face group and from outside (both observers inside the classroom and from home) provided important keys to understand how all these social and cultural conditioners undoubtedly operate, but they also observed the role of the members of a community as something dynamic and not so limited or determined, where it would also be possible to rediscover that agency capacity in a living way, evidencing that existing cultural repertoire to creatively use our own culture, where we can also reach desirable social responses, other possible ways of behaving, and relate to the other that is subject to discrimination processes:

Finally, in the next class session, the speeches were reviewed and the students who had not yet intervened were encouraged to contribute their own conclusions, relating these multiple views from inside and outside the classroom to the EMIC (internal) and ETIC (external) perspectives, as well as with the holistic character of Anthropology in search of comprehensiveness; the meaning of culture/s as models but also from their creative use and how important social changes are often generated from the margins; the need to carry out an exercise in estrangement to distance ourselves from ethnocentric positions; the relationship between social practices and narratives (what is done and what is said); the role of prejudices and stereotypes in exclusion processes, as well as the analysis of institutions such as family and the weight of other educational cultural agents. The conclusion drawn by the group itself on this experience was to show how through the formation of a group with a tendency to homogeneity, they had managed to provide important nuances of the discussed topics, reaching a greater depth of this view defined by the own students as social and/or cultural. In the following sessions of the subject, this base built between all facilitated a better understanding of kinship systems, cultural relativism, and the anthropology of migration. In the development of these topics, the allusions of the group and the teacher to what was expressed and felt in the discussion group were recurrent.

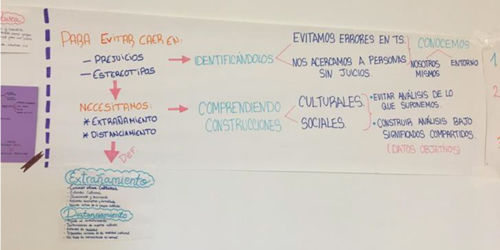

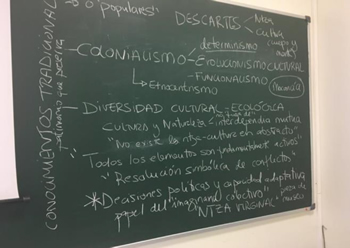

Image 4. Blackboard extract of conclusions drawn from dialogic learning carried out in class

5. CONCLUSIONS

The face-to-face discussion group showed a significant tendency towards agreement and determinism that was broken by the participation of the students who had assumed a distant role from the classroom as an observer, as well as by the introduction of different approaches through the use of the platform's chat from home. This allowed us to understand, from the lived experience, the need to face different positions and have other perspectives when analyzing any phenomenon of social reality. It was especially relevant in this learning that the students discovered themselves to be carriers in their perceptions and evaluations of cultural constructs and collective imaginations, improving their own capacity for distancing and estrangement to enter into the understanding of the described realities. However, it is important to note that the experience described here does not pretend to draw great conclusions about semi-presentiality (this would require a greater systematization of the practice carried out in a contrasted way with different groups), but rather relate this new environment with the curricular and transversal objectives of a subject that carries a significant load of reflexivity.

Despite being students of the first year of Social Work, in a subject located in the first semester, the non-directivity of the group on the part of the teacher did not prevent discourses and fundamental positions from within their own imaginary from emerging to understand the studied phenomena. Through the exposition of diverse nuances, a broader and richer construction of the phenomenon of occupation was achieved, which was being contextualized through dialogue in other logics of inequality and discrimination towards others. The freedom of the discussion group to move through different topics allowed it to conclude by talking about the role of education within these exclusion processes, allowing the participants to modulate their positions assuming other arguments, and allowing a rich, diverse, and meaningful dialogical learning.

Regarding the scope of this research, although it provides possible evidence on the potential that dialogic learning can have as a didactic tool for addressing complex issues that must be subject to strong reflexivity on the part of the actors, it is also necessary to verify its applicability with an expansion of the samples to other non-sectoral or very specific groups, both from formal and non-formal education, even more so if we take into account the variable of semi-presentiality, which would allow us in the future to generate spaces for dialogue and mixed reflection between people, groups, and communities relevant to the different topics to be discussed more easily than the face-to-face environment. Building new shared knowledge from these blended tools linked to participatory action-research methodologies can become a new way of doing and rethinking ethnography, both inside and outside the classroom, as well as the open possibility of working in other possible environments to promote collective processes of diagnosis and social transformation. Because as we have seen, what the people or participating students contribute from outside can serve to introduce key elements not contemplated by the face-to-face dialogue group.

Finally, to conclude that all the topics that appeared through the blended discussion group served, as had happened previously with the face-to-face ones, as channels for the dialogue introduction of the syllabus of the Anthropology subject because, as it was shown in the reading of this work, starting from the diversity of previous knowledge of the students, as well as from the environments through which their learning transits, the construction of new shared knowledge is generated in a more effective, coherent, and enriched way under models that categorize these students as active agents in their own educational processes and not as mere recipients of content. This implies assuming that the role of the students could be equated with that of the subjects who construct the social reality where our objects-subjects of study are located and that from that role they become important sources of reflexivity to delve into the analysis of social facts relevant at present.

REFERENCES

AUTHOR

María Isabel Ralero Rojas

Ph.D. in Social Anthropology. She has a degree in Humanities from the UCLM and Social and Cultural Anthropology from the UCM. She teaches in the subjects of Anthropology in the Degree of Social Work and Methods and Techniques of Ethnographic Research in the Master’s Degree of Applied Anthropology of the UCLM (years 2019-present). University specialist in Immigration and Intercultural Mediation with training and research experience in diversity management at the local level, community intervention, collective construction of knowledge, and coordination of social intervention projects in high diversity neighborhoods that have involved the preparation of monographs and territorial shared diagnoses, gender transversal work, citizen participation, and collective identities. This last area has formed the main topic of her doctoral thesis.

Therefore, she combines university teaching and her research work with Community Social Intervention through Applied Anthropology to promote processes of social transformation.

ANNEX 1. Chat images. Contributions from home to the face-to-face debate