doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.1311

RESEARCH

FILMS ABOUT THE CLIMATE EMERGENCY: A PROBLEM WITHOUT RESPONSIBLE OR SOLUTIONS

CINE EN TORNO A LA EMERGENCIA CLIMÁTICA: UN PROBLEMA SIN RESPONSABLES NI SOLUCIONES

CINEMA SOBRE A EMERGÊNCIA CLIMÁTICA: UM PROBLEMA SEM RESPONSÁVEIS NEM SOLUÇÕES

David Vicente Torrico*

Nereida López Vidales1

1University of Valladolid. Spain

*David Vicente Torrico: Investigador postdoctoral en la Universidad de Valladolid, donde ejerce como profesor en el área de Periodismo. Sus líneas de investigación se centran en la representación mediática del cambio climático y las catástrofes naturales y el estudio de la industria cinematográfica.

ABSTRACT

The film industry has opted to include the climatic emergency in its stories, thus configuring a narrative universe in which the spectator negotiates his identity and his own actions through the situations that appear on the screen. Through the application of a content analysis, our research aims to reveal the discursive keys on which the film discourse is based, paying attention to the thematic variables represented, the construction of the characters and the spaces recreated in the productions shown in Spanish cinemas between 2000 and 2019. The results reveal a biased treatment, both in the selection of variables and in the design of characters and settings, presenting a problem that mainly affects the Western population. In line with the above, the cinematic account of the climate emergency presents the same narrative deficiencies as the informative discourse, thus losing a valuable opportunity to transmit sustainable values. To avoid inaction and complacency among audiences, we make a series of recommendations based on contextualising and empowering civil society through the design of recognisable situations and characters for the audience.

KEYWORDS: Film, Climate emergency, Outreach, Edutainment, Environmental education, Narrative Film, Audience, Story, Plot

RESUMEN

La industria del cine ha apostado por incluir la emergencia climática en sus relatos, configurando así un universo narrativo en el que el espectador negocia su identidad y sus propias actuaciones a través de las situaciones que aparecen en la pantalla. Mediante la aplicación de un análisis de contenido, nuestra investigación persigue desvelar las claves discursivas sobre las que se asienta el discurso cinematográfico, atendiendo a las variables temáticas representadas, a la construcción de los personajes y a los espacios recreados en las producciones exhibidas en las salas españolas entre los años 2000 y 2019. Los resultados revelan un tratamiento sesgado, tanto en la selección de variables como en el diseño de los personajes y escenarios, presentando un problema que afecta principalmente a la población occidental. En línea con lo señalado, el relato cinematográfico sobre la emergencia climática presenta las mismas deficiencias narrativas que el discurso informativo, perdiendo así una valiosa oportunidad para transmitir valores sostenibles. Para evitar la inacción y la autocomplacencia entre el público, formulamos una serie de recomendaciones basadas en la contextualización y empoderamiento de la sociedad civil, a través del diseño de situaciones y personajes reconocibles para la audiencia.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Cine, Emergencia climática, Divulgación, Eduentretenimiento, Educación ambiental, Narrativa, Película, Audiencia, Guion

RESUMO

A indústria do cinema tem investido em incluir a emergência climática nos seus relatos, configurando assim um universo narrativo onde o espectador negocia sua identidade e seus próprios atos através das situações que aparecem na tela. Através da aplicação de conteúdo, a nossa pesquisa procura desvendar as chaves discursivas sobre as quais se apresenta o discurso do cinema, atendendo às variáveis temáticas apresentadas, a construção de personagens, e os espaços recriados nas produções exibidas nas salas de cinema espanholas entre os anos 2000 e 2019. Os resultados revelam um tratamento tendencioso tanto na seleção das variáveis quanto no desenho dos personagens e cenários, apresentando um problema que afeta principalmente a população ocidental. De acordo com o descrito acima, o relato cinematográfico sobre a emergência climática apresenta as mesmas deficiências narrativas que o discurso informativo, perdendo assim uma oportunidade valiosa para transmitir os valores da sustentabilidade. Para evitar inação e a autocomplacência dentro do público, formulamos uma série de recomendações baseadas na contextualização e o empoderamento da sociedade civil, através da criação de situações e personagens reconhecíveis para a audiência.

PALAVRAS CHAVE

Cinema, Emergência climática, Divulgação, Eduentretenimento, Educação ambiental, Narrativa, Filme, Audiência, Roteiro

Correspondence

David Vicente Torrico. University of Valladolid. Spain david.vicente.torrico@uva.es

Nereida López Vidales. University of Valladolid. Spain nereida.lopez@uva.es

Received: 23/02/2021

Accepted: 20/05/2021

Published: 03/01/2022

How to cite this article

Vicente Torrico, D. y López Vidales, N. (2022). Films about the climate emergency: a problem without responsible or solutions. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 155, 1-22. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1311

The article is part of the research entitled “Truth and ethics in social networks. Perceptions and educational influences on young users of Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube (Internética)”, funded by the 2019 Call for R+D+I Projects of the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (PID2019-104689RB-100) and supported by the GIR Digital Culture, Innovation, Creativity, and Social Participation in Communication: OCENDI, from the University of Valladolid

Translation by Paula González (Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Venezuela)

1. INTRODUCTION

The society of the 21st century is facing a climatic emergency, a scientific phenomenon that has been strongly incorporated into the political, media, and social spheres. Not surprisingly, its inclusion among the UN Development Goals, the increase in information coverage (Fernández-Reyes, 2019), and the recent mobilization of citizens (Wahlström, Kocyba, De Vydt, & De Moor, 2019) have acted as catalysts of the story around a problem whose representation has traditionally been marked by more shadows than lights.

Scientific journalism has tried to provide the necessary arguments and tools to facilitate the participation of citizens in the public debate on these issues. However, in practice, tensions between experts and journalists have caused cracks in the story. To the disparity of objectives, criteria, and procedures that guide its productive dynamics (Vicente-Mariño and Vicente-Torrico, 2014), is added the general disinterest of the directors of the media, who relegate science to the background, which translates into the lack of specialization of some professionals who recognize that they are not properly trained or have the necessary means to understand and assess the scientific issues they deal with. The lack of harmony between the two groups that participate in the story could be one of the reasons for the scarce scientific education of the population, a reality that, in the case of the climate emergency, is manifested in almost a third of Spaniards according to the latest surveys carried out by the Elcano Royal Institute (2019).

In the academic field, information coverage of climate change is the most recurrent environmental issue among social science researchers in recent decades (Vicente-Mariño, 2011). The authors point out that it is an intermittent and cyclical story (Carvalho, 2010), relegated to an informative background (León-Anguiano, 2007), and linked to natural disasters and political encounters, thus prioritizing the debate over the need to act (Hulme, 2009). In this way, the media discourse seems far from helping to form an adequate perception of the seriousness of the situation. Despite everything, the public continues to choose the media as their main window to the world (López-Vidales; Gómez-Rubio, and Vicente-Torrico, 2017), with an incidence that reaches up to 71% in the case of the climate emergency (Díez-Nicolás, 2004).

Faced with the limitations inherent to the informative story, environmental education is presented as a formative proposal that seeks to raise the level of general knowledge about the climate emergency through the acquisition of values and behaviors responsible for the environment. With more than half a century of history, and protected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), environmental education is directed to all social strata as a complement to the regulated education that must be developed throughout people's lives. Due to its informal nature, this pedagogical initiative relies on the use of techniques such as educational entertainment (Tufte and Obregón, 2010), a discipline oriented to the acquisition of beliefs and behavior models through the use of popular leisure formats, which results in greater involvement on the part of the participants. Starting from simple ideas, easy to understand, educational entertainment relies on the seductive mechanisms of the media in which it is inserted, such as literature, films, advertising, or video games, to appeal more to emotion than to reason, thus generating a constant flow of stimuli that emerge from popular culture and that, in the case of the climate emergency, are classified under the label of climate fiction or Cli-Fi (Johns-Putra, 2016).

Although the first stories with an environmental theme date from the mid-20th century (Brereton, 2005), with film and literature as the main testbed, their presence has multiplied with the arrival of the new millennium, thus favoring the consolidation of this narrative space. The success of these entertainment formats would reside in the recreation of an everyday environment, the development of an easy-to-follow plot, the use of recognizable characters, and the inclusion of a final moral or teaching (Jones & Song, 2014), driven by the evocative power of the narrative and the seductive capacity of the image (Sheppard, 2012).

However, reception studies show that the effects produced on the public from this type of experience are far from the desired results, thus evidencing the difficulty of developing effective communication to combat the climate crisis. Vicarious experiences, as Sakellari (2015) points out, can generate a great impact in the short term, but they do not manage to modify the behavior of the audience. In the same line, Arendt and Matthes (2016) manifest, for whom the story reinforces the interest of the audience already familiar with the subject, but fails to convince neutral viewers. Among the reasons that could justify this low awareness are the sensationalist approach, the complexity of the plots, the lack of credibility of the characters, and, lastly, the repetition of speeches already broadcast through the media (Vicente-Torrico, 2017).

Therefore, and based on these antecedents, we propose to analyze the cinematographic representation of the climate emergency and evaluate its degree of adequacy regarding the criteria that favor adequate social awareness.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main interest pursued by our research is to check the validity of the cinematographic story as an educational tool in the face of a climate emergency. To do this, we propose a study of the discursive variables present in films that address this reality to develop a catalog of recommendations that allow promoting awareness in this type of narrative.

With this horizon in mind, we pose the following research questions:

The starting hypothesis indicates that the cinematographic story offers a biased and sensationalist vision, far from the principles suggested by the environmental narrative to raise awareness and promote the adoption of attitudes and behaviors that respect the environment, and favors, on the contrary, inaction and the self-indulgence of the public who come to the cinema and expose themselves to this type of message.

This statement is based on the predominance of consequences over the analysis of causes and the search for solutions; in the generalized adoption of the subjective point of view of those affected, instead of denouncing the participation of those responsible or highlighting the voices of alarm that come from expert groups and environmental organizations; and in the recreation of scenarios that take the viewer away from the problem.

3. METHODOLOGY

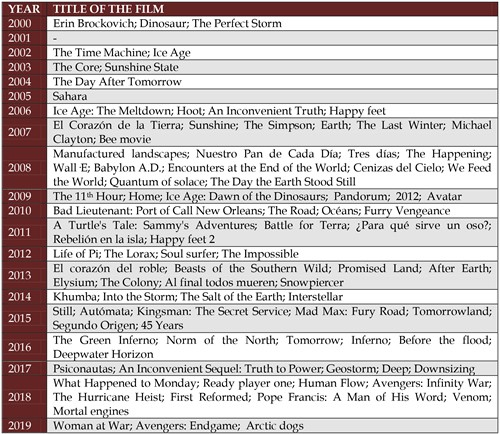

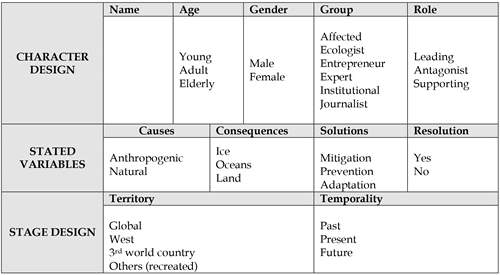

To answer the questions raised and meet the objective of using films as an educational tool, we resorted to an analysis protocol specifically designed for the study of this type of material (Vicente-Torrico, 2017), inspired by the methodology on which the main studies on the informative coverage of the climate crisis in the traditional media, already mentioned in the introductory chapter, are based.

The inherent characteristics of a cinematographic narrative, with longer-lasting pieces and a language loaded with abstraction and symbolism, require a correct combination of the objective and systematic nature of content analysis with the capacity for interpretation to describe not only what is manifested in the message, but also what is latent (Krippendorff, 1990). In this way, we reveal the characteristics of the story according to its theme, the characters, and the settings in which the action takes place. For the detection of these signs, a previous coding sheet has been designed that combines the quantitative and qualitative study, and that comprises a total of 32 fields distributed in three categories: the design of the characters, the stated thematic variables, and the setting of the stage.

Table 1. Analysis instrument

Source: self-made

The titles that make up the analysis sample are the cinematographic productions exhibited in Spanish theaters between 2000 and 2019. To elaborate this corpus, we have relied on the list prepared by the International Environmental Communication Association (IECA) [1] , in specialized cinematographic information portals such as IMDB [2] , and the database provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport (MECD by its acronym in Spanish) [3] , adopting only those titles whose line of argument addresses any of the issues related to the climate emergency, such as its implications in environmental matters, health, safety, economy, mobility, housing, resource management, or the search for alternative energies, some thematic categories that emerge from the recommendations made by researchers who study the coverage of the climate emergency in the traditional media.

In this way, we have managed to advance from a wide compilation of cinematographic productions towards a representative and a technically operational sample of the audiovisual offer distributed over the last 20 years in the Spanish market, thanks to the use of different conceptual filters (time and thematic criterion and commercial circuit) that have progressively limited the number of results until reaching the final sample, which is made up of a total of 92 titles (see annex).

[1] https://theieca.org/filmography-nature-and-environmental-movies

[2] https://www.imdb.com

[3] http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/cine/mc/catalogodecine/inicio.html

4. RESULTS

The analysis of the elements that make up the cinematographic discourse allows us to reveal, through their presence or absence, the main themes that define the representation of the climate emergency, as well as the figures that act as primary definers of this reality and the scenarios where the different plots unfold.

4.1. Study of thematic variables

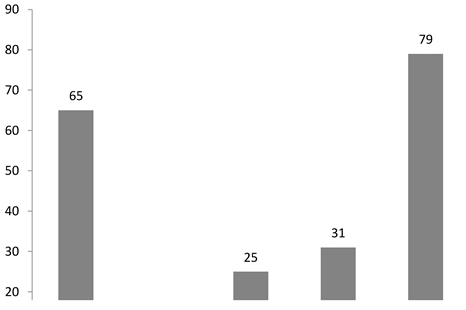

The study of the thematic variables reveals the predominance of the impacts, present in 93% of the productions (n=86/92), ahead of the enunciation of the causes (80%, n=74/92) and the proposal of solutions (79%, n=73/92), as shown in the following image. This circumstance, already relevant in itself, will be shelled in the following paragraphs because the cinematographic story simultaneously incorporates several of the analyzed thematic categories in its script.

Source: self-made

Figure 1. Movies in which each thematic category appears

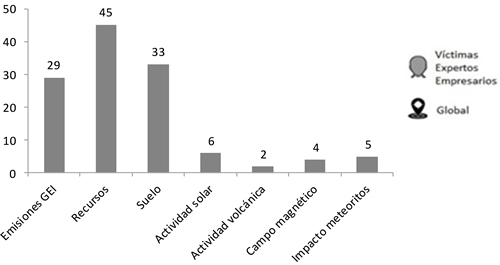

The analysis of the causes alluded to in the different projects provides relevant indications regarding the attribution of guilt and the search for those responsible. In this case, and taking into consideration the two ideological currents that lead the environmental debate, we propose the study of the anthropogenic influence on climate and the analysis of the natural agents that can affect life on the planet. In this sense, the obtained results demonstrate the clear predominance of causes associated with human intervention (83%) over those of natural origin (17%).

Within the anthropogenic causes, the variables that correspond to the access and use of resources (42%) prevail over the problems associated with land management (31%) and the emissions derived from the use of fossil fuels, which appear in 27% of the cases. In this way, activities related to waste management, the primary sector, deforestation, or urban speculation have a greater presence on the screen than those related to pollution, whether through industry, transport, or energy consumption in the domestic sphere.

Regarding natural causes, those responsible for the films highlight solar radiation (35%) and the impact of meteorites (29%) as the main threats, ahead of variations in the magnetic field (23%) and volcanic activity (13%). Although, as we have already pointed out, the attribution of responsibilities falls mainly on the human being, natural factors play a crucial role in the cinematographic story, as they are the trigger for the plot in 8 of the analyzed titles.

The social agents that participate in the definition of the causes are a total of 255, and they are led by the group of anonymous victims of the climate emergency (35%), far exceeding the group formed by experts (22%). While the former point to the human being as responsible for the problem (86%), the scientific discourse presents a holistic view of the environmental crisis because they dedicate a quarter of their interventions to analyzing the influence of natural agents on the climate. The business sector, responsible for this situation in the eyes of public opinion, appears in third place (18%), and its story revolves mainly around activities related to access and use of land.

Films that address the causes of the climate emergency present this problem from a global perspective (47%). Western countries (27%) occupy the second position, ahead of the recreation of alternative territories (19%). Consequently, the cinematographic narrative exempts developing nations from all blame, which barely host 7% of the analyzed titles.

Source: self-made

Figure 2. Cinematographic representation of the causes of the climate crisis

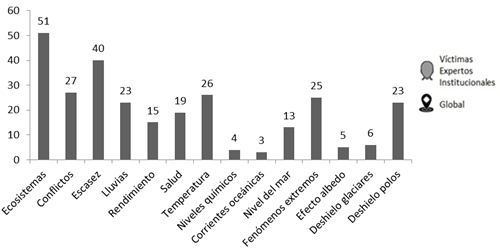

The study of the consequences contributes to the definition of the climatic emergency, establishing a cause-effect relationship in the representation carried out by the film industry. This section includes the impacts produced on the frozen surface, the effects generated on the oceanic surface, and the consequences derived from the climate crisis on the earth's surface.

The results obtained show that the cinematographic discourse opts for showing the effects produced on the continental territory (72%), in line with the anthropocentric perception of the natural environment. In the second place, and at a notable distance, are the impacts generated on the oceanic surface (16%), which manage to obtain a higher share of the screen than the frozen territories (12%).

At the specific level, the effects on the earth's surface are written in terms of action and drama, and, to a lesser extent, through animated titles. Therefore, the most recurrent variables will be linked to the suffering of the characters, either through the loss of biodiversity (25%), the scarcity of resources (20%), conflicts and migratory movements (14%), and health conditions (9%). On the other hand, the consequences related to the changes experienced by natural parameters, such as changes in temperature (13%), rainfall cycles (11%), and loss of crop yield (8%) receive less attention, and their presence is subject to documentary productions.

In the case of variables related to the oceans, the cinematographic story establishes a clear division between evolutionary and disruptive phenomena. In this way, the first group is made up of changes in ocean currents (7%) and the chemical composition of water (9%), in a technical story that finds accommodation in the documentary genre. On the other hand, the rise in sea level (29%) and the formation of extreme natural phenomena (55%) represent important narrative turns, and become fundamental elements for drama and action.

The descent of the frozen surface is one of the symbols of the climatic emergency, although for the film industry it has hardly any visibility. Using a didactic approach, the documentary story describes the albedo effect (15%) and the consequences linked to the melting of glaciers (18%), while the retreat of the poles (67%), which is the dominant variable in this section, appears in all types of genres.

Taking into account the characteristics of the characters, the group that stars in the story of the consequences is that of the victims (37%). This is followed by groups of experts (24%) and institutions (10%), which, whether in documentary or fiction, are involved in heated confrontations over the effects of the climate emergency. The visual appeal of natural catastrophes facilitates the inclusion of the journalistic union (8%), which finds its place as the primary definer of the environmental threat from the very scene of the events.

In geographical terms, the impacts of the climatic emergency are shown in a global key (51%), driven by the presence of problems related to frozen and oceanic surfaces. The western variable also obtains high visibility (25%) and stands out in the representation of problems on the earth's surface. The consequences suffered by developing countries are once again invisible (7%), even lagging behind the recreated scenarios (17%).

Source: self-made

Figure 3. Cinematographic representation of the consequences of the climate crisis

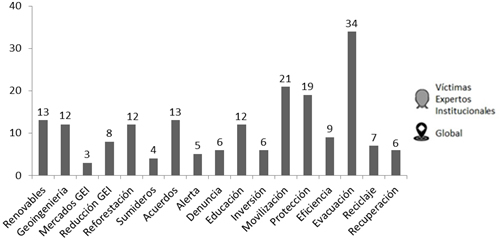

The adoption of an adequate treatment to combat the effects of a problem requires starting from a correct definition of it. Once the first two components of the cinematographic message have been analyzed, we conclude our analysis of the thematic variables by studying the measures reflected by films.

According to the data obtained, the proposals to mitigate the impact of the climate crisis obtain the least representation (27%) in the thematic study, in a discourse that favors prevention measures (43%) and adaptation to the new circumstances of the environment (30%).

Among the mitigating solutions, aimed at eradicating the climate emergency, renewable energies (25%) and the reforestation of forests (23%) stand out, both present in all cinematographic genres. Geoengineering (23%) takes center stage in fiction cinema, through the recreation of various experiments that constitute the axis of the story. The rest of the measures, with a more technical nature, such as the reduction of polluting gases (15%), their capture in sinks (8%), or the negotiation of emission rights (6%), appear linked to the documentary story.

Measures aimed at preventing damage in the face of already unavoidable impacts could be divided between official and social. Among the former, dependent on the public powers, are the protection of the environment and its species (23%), the adoption of political agreements (16%), environmental education (15%), investment in infrastructures adapted to the new conditions (7%), the implementation of control and reporting mechanisms (7%), and the design of an early warning system (6%). The second group has a vindictive character and includes environmental mobilizations (26%), which are the most recurrent variable in this thematic section.

Regarding the adaptive proposals, the cinematographic story opts for evacuation (61%), a variable that stands out in fiction and animation scripts. Solutions aimed at favoring coexistence with new weather patterns, such as technological efficiency (16%), recycling (13%), and the recovery of damaged environments (10%) receive less attention, although their presence has been detected in all the analyzed cinematographic genres.

The sources that participate in the story about the solutions appear headed by the group of victims (24%), due to their high presence in the evacuation section. A short distance away is the group of experts (23%), whose contribution to the cinematographic portrayal focuses on mitigating solutions. In the third position, we find public representatives (14%), with a similar weight to environmental and business groups (13%), who benefit from social unrest and technological progress, respectively, to gain visibility.

The scenarios in which the plots related to the solutions take place once again place the global approach in the first place (54%), doubling the number of stories that take place in Western countries (27%). What is relevant about these results is that, once the impact is inevitable, the action takes place in the recreated territories (14%), drawing a complicated horizon. This fact has a final reading, and it is that developing countries (5%) hardly participate in the reconstruction of the planet, and depend on the protection that the great world powers offer them.

Source: self-made

Figure 4. Cinematographic representation of solutions to the climate crisis

To close the section dedicated to solutions, we have analyzed the degree of effectiveness of the proposals that appear in the cinematographic story. The outcome of the different plots indicates that only in 42% of the cases a satisfactory resolution has been reached, while in the remaining 58% the efforts made by the characters to reverse the situation are sterile.

In this virtual testbed that are films, the first stories bet on a positive resolution of the problem and give their characters the ability to return the planet to its state of equilibrium. However, after the premiere of An Inconvenient Truth (2006) a more critical approach is adopted, in which catastrophes are so complex that the problem cannot always be tackled. In this period, the cinematographic genre plays a fundamental role because animation is going to become the last stronghold for humanity, through the classic happy ending. On the contrary, documentary cinema, aimed at an adult and critical audience, shows a pessimistic conception about the future of the planet, despite the proposed measures.

Among the mentioned solutions, prevention obtains a higher success rate (53%), ahead of adaptive measures (31%) and mitigating measures (16%), in a discourse that seems to suggest that the climate emergency is already an inevitable fact. At a specific level, the proposals that enjoy greater acceptance by those responsible for the productions would be reforestation, geoengineering, economic investment, social mobilization, protection of the environment, and, although with a meager margin, the evacuation of the population towards safe territories.

4.2. Study of the characters involved in the story

The next section to consider in our content analysis is the study of the characters that participate in the cinematographic representation of the climate crisis since these figures affect the identification mechanisms that are generated in the viewer and play a fundamental role when defining the object of study.

Although the results of the thematic variables present some relevant indications regarding the role of the characters, we have thought it appropriate to collect in a separate section all the data that allow us to advance in the analysis of these elements.

The first differential feature that we have analyzed is the ascription of the characters to a certain group, generally linked to their profession. Thus, we verify that the largest group is made up of the victims of the climate crisis (38%), far ahead of the group of experts and public representatives, who reach a representation of 15%. The business sector includes 13% of the characters, while journalists and environmentalists reduce their presence to 8%. The remaining percentage would correspond to the narrators of the action in off (3%).

If we analyze the demographic data of the cast that participates in the representation of the climate emergency in films, we verify that almost two-thirds of these figures correspond to the profile of the middle-aged man. Consequently, female roles (22%) or the youngest members of the cast (9%) go unnoticed. Besides their small number, these figures will play a supporting role in the story, generally associated with victims or environmental movements.

Finally, we must review the existence of dissenting voices in the story, in what has become known as climate deniers. These figures, who question the scientific consensus in the face of the climate emergency, promote an alternative definition of the problem through antagonistic roles and declarative frames. Religious allusions (1%), which equate scientific knowledge with the existence of a divine force, show a high level of roots among victims in developing countries. Climate skeptics (9%), driven by lobbies whose activity is related to the ecological footprint, appear to be located in western countries and, despite their final redemption, play the role of antagonists for most of the story. It is also possible to find them in documentary cinema, through archival statements.

4.3. Analysis of the scenarios/territories

The delimitation of the space in which the action takes place is the last section of our analysis and provides an additional reading to the variables studied so far. As has been pointed out in the introductory chapter, the climatic emergency is defined in terms of distance, both physical and temporal, so the study of these coordinates allows us to delve into the representation of the phenomenon.

Throughout our study, we have detected a total of 364 different scenarios, of which 37% correspond to western territory, compared to 9% of developing countries and 19% of recreated places. The global variable, when the story is developed simultaneously in several spaces at the same time, adds up to 35% of the total.

At a specific level, we verify that the main focus of attention is the United States, whose presence in the cinematographic discourse accounts for 29% of cases, and has more impacts than all developing countries combined. The country factor applied to the sample affects this section, placing Spain as the second most relevant territory (9%), ahead of larger countries such as China (7%), United Kingdom (6%), Brazil (4%)), or India (3%). On the other hand, the African continent and the Pacific islands have a testimonial presence throughout the research.

This unequal treatment is also evident in the analysis of the variables that are represented in each scenario. In this way, the anthropogenic origin of the climate crisis is associated in two out of three cases with advanced societies, while in the approach to natural causes the recreated scenarios play an important role (38%), from a dystopian future in which humanity has collapsed. The alteration of the natural patterns of the climate is approached in an international key, while the most disruptive consequences, such as the rise in sea level or the great natural phenomena, hit the West. Evolutionary effects, such as the scarcity of resources and the conflicts that this causes, appear in developing countries. The poorest areas of the planet hardly participate in measures to combat the threat, and they limit their ability to react to evacuation. Modern societies concentrate the bulk of solutions, whether mitigating, preventive, or reactive, although the cinematographic story hides a last resort, the recovery of the planet in a future time, from a recreated scenario (20%).

5. DISCUSSION

The results presented confirm that the impacts of the climate crisis represent the main entry point to the reality of this phenomenon in the cinematographic story. These indications coincide with the coverage made by the traditional media, whether in the press (Young & Dugas, 2011) or television (Djerf-Pierre, 2012).

The representation of the causes of the climate emergency in films shows the same deficiencies as its journalistic coverage. As Gunster (2011) points out, the discourse around the causes presents a very superficial approach, without delving into how the population contributes to this problem with their diet, means of transport, leisure, or housing. Furthermore, a direct connection with the consequences is rarely established, nor are those responsible pointed out (Brereton, 2005).

The general absence of exemplary behaviors and solutions available to the public reflects a trend that has also been detected in the discourse produced by the media. Thus, authors such as Shwom, Dan, and Dietz (2008) link the low perception of self-sufficiency and involvement of the population to the reduced presence of measures available to the public in the daily story.

The design of the cinematographic characters contradicts the distribution of times recorded in the traditional media, where institutions and experts star in a story in which the victims appear last (Young & Dugas, 2011). However, our results show certain similarities with catastrophe journalism (Rodríguez and Odriozola-Farré, 2012).

Besides the group to which the characters belong, their demographic study reproduces the representation model of the media, where women and young people, who are the social groups most involved in defending the environment, receive less journalistic attention (Corner et al., 2015).

The scenarios in which the analyzed plots are developed are concentrated in the Western world, leaving aside those territories most affected by the climate crisis, such as developing countries and the Pacific islands. Brereton (2005), in his review of the representation of environmental problems during the 20th century, defines the United States as the quintessence of postmodernism and the propitious place for the development of all kinds of catastrophes, an idea shared by González Alcaraz (2014) in his study on the Latin American press.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Following the objectives set in the research, throughout the results chapter we have presented the relationship of thematic variables that determine the cinematographic representation of the climate emergency, through the application of a methodological design based on content analysis. In this way, and after having analyzed a total of 92 films, we proceed to evaluate the validity of the cinematographic story as an instrument for raising awareness in the population.

In the thematic section, our starting point ventured a biased story, with a marked predominance of the most destructive effects compared to the critical analysis of the causes, the search for culprits, and the promotion of solutions. The results presented confirm that the impacts of the climate crisis are represented in 93% of the films, and are enunciated by three out of four characters, which is why they represent the main entry point to the reality of the phenomenon. Within this category, the story focuses on the variables that represent a disruptive threat. On the contrary, the evolutionary effects, linked to the alteration of natural patterns, specifically appear in the documentary story.

The second thematic category by the number of appearances corresponds to the causes, which are present in 80% of the analyzed titles. The fact that several of the stories begin in a dystopian future, without referring to the reasons that led to this situation, significantly contributes to the decontextualization of the problem. Although the cinematographic story gives a clear predominance to human factors, whose presence multiplies by five the arguments about the natural origin of the phenomenon, its self-critical character is reduced to the documentary genre and presents a sweetened portrait of the current production and consumption system.

The issue with the least representation in the cinematographic discourse corresponds to the proposal of solutions, present in 79% of the works. In fact, if we take into account the effectiveness rate of these measures, we find that more than half of the titles conclude without having applied any type of solution, which disables the public to adopt a pattern of responsible behavior, thereby promoting inaction and self-indulgence. The low presence of small gestures, such as recycling or energy efficiency, contributes to this idea, measures available to a public that could feel empowered to act through this model.

Therefore, and from the thematic point of view, we have been able to confirm that the cinematographic narrative tends to prioritize the most spectacular aspects of the problem in a representation of the climate crisis that sins as sensationalist.

The second research question analyzes the presence and functions of the different groups that participate in the public space, and the results have confirmed that the camera mainly adopts the point of view of the victims. With a presence of 38%, their perspective is perfect to add drama to the script, since it exposes a vulnerable character to a threat for which, a priori, he is not responsible. The group of experts, socially recognized as the most reliable source to address this situation, accounts for 15% of the sample, and their presence is divided between the informative statements of documentaries and the role of superheroes in fiction cinema, in a distorted portrait of this group. On the contrary, the two groups that a priori we consider responsible for the deterioration of the planet, the business sector and the public representatives, confirm their antagonistic role through a caricature profile or montage by contrast.

Along with the above, the construction of the characters presents two important factors for improvement from the point of view of environmental awareness: on the one hand, the anthropomorphic figures (19%) generate empathy among the public, but limit identification with them; on the other, the profile of the analyzed character responds to the middle-aged western male, thus excluding young people, women, and other ethnic groups. Therefore, we can conclude that from the point of view of the characters, a sensationalist and discriminatory story is also presented.

The third point of our analysis refers to the definition of the space in which the action takes place. From the obtained results, we verify that films recreate an easily identifiable territory for the western public. This closeness could reduce the psychological distancing from the problem, placing the most immediate environment, possessions, and the audience’s loved ones at risk. However, the Eurocentric nature of the narrative, with the West as the epicenter of the climate emergency, leaves the most affected territories out of focus, such as developing countries and the Pacific islands. These scenarios, usually located on the margins of the story, remain outside the decision-making process and the implementation of solutions to combat the problem.

In short, the obtained conclusions present a cinematographic story with lights and shadows, in which we have been able to confirm our initial hypotheses. Based on the results presented, we can point out that films take a sensationalist approach, both from the thematic point of view and the design of the characters since it encourages the human, disruptive, and dramatic approach to the phenomenon. For these reasons, it is not possible to expect a greater commitment in the fight against the climate emergency on the part of the viewer compared to the audience of traditional media because both narratives present the same deficiencies.

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

In line with the last of the objectives set, we proceed to offer a series of recommendations that would contribute to enhancing the awareness capacity of the environmental story. This point, however, should be considered as the proposal of a new line of work and never as a prescriptive approach since our project is raised from the strictest analytical plane of the researcher, for which we have used the narrative deficiencies exposed in the consulted literature. Possible improvements to be made in the stories of the future should include: 1) greater contextualization, giving more presence in the plot to the causes that originated the problem; 2) an empowering message, showing the small gestures that allow the viewer to contribute to the fight against the climate crisis; 3) a greater presence of experts and, especially, of environmental groups, whose speech and example serve the interests of awareness-raising work; 4) a process of female, youth, and ethnic empowerment because, in the current discourse, the majority of the world population is excluded, thus making it difficult for them to identify as active agents; and 5) to show people, instead of the presence of humanized beings and animals because these types of figures make it difficult for the audience to get involved.

REFERENCES

AUTHOR/S

David Vicente Torrico

Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Valladolid, where he works as a professor in the area of Journalism. His lines of research focus on the media representation of climate change and natural disasters and the study of the film industry. He is part of the recognized research group Ocendi (Observatory of Leisure and Digital Entertainment and collaborates in Climántica's environmental workshops.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0379-6086

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=3DMiJ-0AAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/2165115907-David-Vicente-Torrico

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=56340374000

Academia.edu: https://uva-es.academia.edu/DavidVicenteTorrico

Nereida López Vidales

Professor of the Degree in Journalism at the University of Valladolid. She is a Doctor in Political Science and Sociology, Journalist, Political Scientist, and Master in Radio Production. She has worked in various media and combines university teaching with the direction of the Observatory of Leisure and Digital Entertainment (GIR OCENDI), the direction of Radio UVa, and the Coordinations of the Degree in Journalism and the ELLCOM Doctorate Program (UVa). Her lines of research are audiovisual technology, radio and television, the evolution of professional profiles, young people and trends in media consumption, and the creation of new content. She has published several dozen scientific articles and eleven books.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6960-6129

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=d-h-uasAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nereida_Lopez_Vidales

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=56009001000

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/nereidalopez

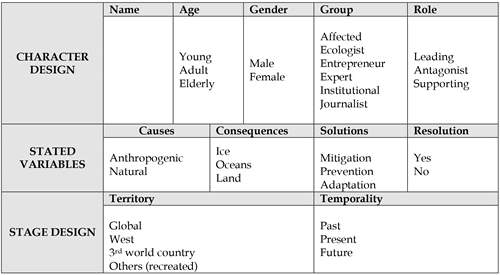

Annex 1. List of films that make up the analysis sample