doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.149.127-151

RESEARCH

ETHNIC MEDIA, ADAPTATION TO THE DIGITAL ECOSYSTEM AND USES OF THE MIGRANT DIASPORA

MEDIOS ÉTNICOS, ADAPTACIÓN AL ECOSISTEMA DIGITAL Y USOS DE LA DIÁSPORA MIGRANTE

MEIOS ÉTNICOS, ADAPTAÇÃO AO ECOSISTEMA DIGITAL E USOS DA DIASPORA IMIGRANTE

Enrique Vaquerizo Domínguez1

1Camilo José Cela University. Spain

ABSTRACT

This article addresses the current situation of ethnic media, spaces traditionally destined for migrant communities, which, far from their preconceived extinction, have survived and find new possibilities through conservation and in many cases renewing their role as identity gratifiers. Today they still conserve a space of importance in terms of consumer preferences on the part of these groups, although they have had to adapt to the digital ecosystem introducing substantial changes in their business model, structures and content production adapted to the digital environment. These pages explore and compare content, organizational structures, tools and editorial lines of two ethnic media related to the migrant community of Mexicans in the United States, one born with exclusively digital and transnational vocation as Conexión Migrante and the other adapted from a printed format to the community of Mexicans in New York as Diario de México in the USA. The research focuses mainly on finding out if these media would be privileging the maintenance by migrants of their links with the society of origin or, on the contrary, the cultural assimilation in their new destination, and in what way, the move to a digital format with more interactive and horizontal structures help in these processes.

KEY WORDS: migration, ethnic media, virtual diaspora, Migrant Connection, Facebook, polygamous space, Diario de México in U.S.A

RESUMEN

El artículo aborda la situación actual de los medios étnicos, espacios tradicionalmente destinados a las comunidades migrantes, que lejos de su preconizada extinción, han sobrevivido y encuentran nuevas posibilidades a través de la conservación y en muchos casos renovación de su papel como gratificadores identitarios. Hoy conservan aún un espacio de importancia en cuanto a las preferencias de consumo por parte de estos colectivos, aunque han debido adaptarse al ecosistema digital introduciendo cambios sustanciales en su modelo de negocio, estructuras y producción de contenidos adecuados al entorno digital. Estas páginas exploran y comparan de forma cualitativa contenidos, estructuras organizacionales, herramientas y líneas editoriales de dos medios étnicos relacionados con la comunidad migrante de mexicanos en Estados Unidos, uno nacido con vocación exclusivamente digital y transnacional como Conexión Migrante y el otro adaptado desde un formato impreso a la comunidad de mexicanos en Nueva York como Diario de México en U.S.A. El artículo pretende definir las nuevas estructuras, líneas de contenidos y modelos de negocios adoptados por los nuevos medios étnicos y qué conexiones guardan con sus funciones tradicionales. Del mismo modo investiga si estos medios estarían privilegiando el mantenimiento por parte de los migrantes de sus vínculos con la sociedad de origen o por el contrario la asimilación cultural en su nuevo destino, y de qué forma, el paso a un formato digital con estructuras más interactivas y horizontales ayuda en ese proceso.

PALABRAS CLAVE: migración, medio étnico, diáspora virtual, Conexión Migrante, Facebook, espacio poligámico, Diario de México en U.S.A

RESUME

O artigo aborda a situação atual dos meios étnicos, espaços tradicionalmente destinados às comunidades imigrantes, que longe de sua preconizada extinção, sobrevivem e encontram novas possibilidades através da conservação e em muitos casos renovação de seu papel como gratificadores identitários. Hoje ainda conservam um espaço de importância enquanto as preferências de consumo por parte destes coletivos, embora deveram adaptar-se ao ecossistema digital introduzindo mudanças substanciais em seu modelo de negócio, estruturas e produção de conteúdos adequados ao entorno digital. Essas páginas exploram e compraram de forma qualitativa conteúdos, estruturas organizacionais, ferramentas e linhas editoriais de dois meios étnicos relacionados com a comunidade imigrante de mexicanos nos Estados Unidos, um nascido com vocacional exclusivamente digital e transnacional como Conexion Migrante e o outro adaptado desde um formato impresso a comunidade de mexicanos em Nova Iorque como Diario de México em U.S.A. O artigo pretende definir as novas estruturas, linhas de conteúdo e modelos de negócios adotados pelos novos meios étnicos e qual conexões guardam com suas funções tradicionais. Do mesmo modo investiga se estes meios estariam privilegiando por parte dos imigrantes de seus vínculos com a sociedade de origem ou pelo contrário a assimilação cultural em seu novo destino, e de que forma, a passagem a um formato digital com estruturas mais interativas e horizontais ajuda neste processo.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: imigração, meio étnico, diáspora virtual, Conexion Migrante, Facebook, espaço poligâmico, Diario de México en USA

How to cite the article: Vaquerizo Domínguez, E. (2019). Ethnic media, adaptation to the digital ecosystem and uses of the migrant diaspora. [Medios étnicos, adaptación al ecosistema digital y usos de la diáspora migrante]. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, (149), 127-151.

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.149.127-151

Recovered from http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1180

Correspondence: Enrique Vaquerizo Domínguez: Camilo José Cela University. Spain.

enrvaque@ucm.com

Received: 29/04/2019

Accepted: 17/06/2019

Published: 15/12/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

In this century, the massive increase in migratory flows and the creation of increasingly multicultural societies has also had consequences in the communicative scenario. The media have become aware of the emergence of attractive new consumer niches represented by migrant groups for whom identity links become the password. Several authors Johnson (2000), Shi (2005), Houssein (2013) Melella (2016) and Ramasubramaniam et al. (2017) agree that one of the most frequent justifications for the election of media consumption by migrants is to keep their collective identity.

On the other hand, the reduction of the digital access gap has enabled large layers of the population to consume, and even produce, the cultural contents that interest them, thanks to the opportunities offered by some ICT, especially social networks. Such opportunities are being well used, among other groups, by the migrant communities to reformulate the media discourse in which they were traditionally relegated to mere passive subjects to become producers of their own symbolic space. In this new setting, the ethnic media, traditional channels intended for migrant communities, far from the predictions that predicted their extinction at the beginning of the century, have survived and, in many cases, exploited new possibilities of linking with their audiences. At present they still retain a significant role in terms of consumer preferences by migrant communities, although they have had to adapt to the digital ecosystem by introducing significant changes in their business model, production structures and content lines.

The press devoted to migrant communities has traditionally been based on the importance of the concept of otherness within the immigrant experience; that is to say, the matrix linked to the modes of social differentiation and categorization in the face of the others that works according to elements such as origin, cultural and ethnic belonging, sex and social class (Rodríguez, 2008). Especially that of ethnicity, it is a recurring element in research on the media aimed at migrant groups. This way, the concept of “ethnic press” has been used on numerous occasions as a way of differentiating to group those media aimed at ethnic or cultural minorities.

According to studies focused on this aspect (Johnson, 2000; Shi, 2009; Georgiou, 2010; Yin, 2013) “ethnic media” can be defined as those media created “by and for” the minority communities residing and in a certain country and who are backboned by a common ethnic factor different from the rest of the groups the host society shares with. Ethnic media were originally established by various minority migrants, who, in many cases, lived border-related realities, to maintain and develop their own cultures and cohere ethnic identities that should give meaning to their subjectivities.

Within this categorization of “ethnic media”, there has always been a broad amalgam of characteristics and intentions. More specifically, Kanellos (2000), when speaking of the so-called “ethnic press in the United States”, distinguishes between “immigrant press”, focused on the informative production of content related to the migrants’ countries of origin, the “Press of native Hispanics”, more focused on civil rights and social and economic development of the community, and finally the “press in exile”, created by political refugees, which offers critical news for their countrymen, trying to border the censorship of power in their home territory.

Despite this diversity, we could point out that the “ethnic press”, mainly its newspapers, has traditionally been linked to a role of information provider. Information focused on interests for the group to whom it is addressed. Sometimes, this function has faced a dilemma: to act as a vehicle that facilitates assimilation in the host society or, on the contrary, the identity reinforcement.

Ethnic media have tended, especially in their origin, traditionally to highlight the differential aspect of emigrated communities. Newspapers contributed to the representation of a symbolic community, but attached to a specific geographical space, of which their readers were part. For example, in the case of the United States, the ethnic press has traditionally been dedicated to the defense of a cultural legacy and the assimilation or integration of minorities within its society.

However, as Rodríguez (2008) points out, over time, and without completely abandoning their role as defenders of the interests of the ethnic groups they represented, many of the publications in Spanish progressively moved away from this political and vindicating line to expand their readers’ base and arouse the interest of advertisers with more commercial content. Currently, the ethnic press is orbiting the identity factor as an element of connection with its public, as well as appearing as reference when meeting their needs and providing them with rewards, in many cases of an identity type. In both scenarios, “ethnic media”, adapted, more or less effectively, to the digital ecosystem continue to play a relevant role.

2. OBJECTIVES

Taking into account the contributions of the literature published so far and the analysis of two representative cases of a migrant community of great vitality such as the Mexicans in the United States, this article aims to achieve the following general objective: analyze, through two concrete examples, the new structures, content lines and business models adopted by the new ethnic media adapted to the digital ecosystem and what connections they have with the functions of traditional ethnic media. From this general or primary objective, I will develop several secondary objectives:

3. METHODOLOGY

The general and specific objectives are achieved through a qualitative methodological treatment developed in three steps: 1. Theoretical research on the state of the art through bibliographic analysis. 2. Comparative analysis as an example of two virtual ethnic media corresponding to the Mexican community in the United States through two of their main formats such as their website and their Facebook page 3. Interviews with those responsible for both media: Patricia Mercado in the case of Migrant Connection and Germán Baz in the Newspaper of Mexico in the USA to compile information on history, structure, objectives and business model after joining the digital system.

The bibliographical analysis of the ethnic media has served as a basic methodology, referring to specific cases, to deepen a reasoned discussion that should provide consistent results when integrating the objectives. So far, this bibliography has focused mainly on the conditions in which media consumption by migrants occurs, what kind of rewards they respond to and whether they encourage integration in the new host context or, on the contrary, reinforce the identity links with the society of origin. Framed within the first scenario, Research by Johnson (2000), Shi (2005) Mendieta (2009), Houssein (2013), Ramasubramaniam et al. (2017) and Brantner and Herczeg, (2013), among others, have been taken as reference. The general theme of these authors defends that ethnic media play an important role in the life of migrant groups, covering, on the one hand, their need for entertainment but also for information and preservation of their cultural identity.

From the point of view of adapting ethnic media to the Internet, the work carried out by the Center of Community and Ethnic Media of the University of New York stands out. From this work, Matsaganis’s study “Ethnic Media in Digital Era” (2018) coordinated by Sherry S. Yu and Matthew D. Matsaganis or “The New York Ethnic Media in the Digital Era” (2016) stand out. Also the work of Cecilia Melella on “The presence of migrant newspapers on the Internet and the challenges of the analysis of virtual social networks” (2013). All address the more or less explicit continuity of the new ethnic media with respect to their previous functions. The analysis of these latest works will serve to address the changes, difficulties and new opportunities that have emerged within these media to maintain their importance among migrant communities in the face of the change in the rules of the game.

On the other hand, this article has chosen two case studies belonging precisely to the conglomerate of media aimed at migrants in the United States, specifically the Mexican community. The two areas have been selected based on a significant audience, but also because of original concepts and contexts and utilities that migrants find to be different in the migration process. These differences are based on variables such as age of the medium or years in the host country. However, both have similarities in their daily functioning marked by a predominance of the digital aspect. On the one hand, the newspaper Migrant Connection came out in 2015, it constitutes a medium born with an exclusively online and transnational vocation aimed at Mexican migrants in the United States, as well as their families in Mexico, this space provides practical information offering services related to migratory procedures and focuses on highlighting the links with the home society. On the other hand, the Newspaper of Mexico in the USA, with headquarters in Mexico City, is one of the deans of ethnic media aimed at the Mexican community in the United States with more than 15 years of existence. Until February 2018, it was printed every day. Today and after an economic restructuring, it only publishes the online version of its header.

In both cases, analytical and descriptive methods have been used to study how their content lines work, as well as their dynamics, forms of participation and interaction among their users, always from the perspective of representing the ethnic and cultural identity and the communication processes that occurred in them. Both the analysis of contents and interactions and the interviews with their managers were carried out in different periods between the months of January and March 2018.

4. SOME CONSIDERATIONS ON THE PASSAGE FROM THE ANALOGICAL TO THE DIGITAL FORMAT IN THE ETHNIC MEDIA

The ethnic press, far from making migrants visible only as victims, a recurring image of this group in many generalist media, has traditionally been in charge of presenting them also as actors fighting for their social, economic and political rights. These communities, which often represent minority cultures in the host society, have in recent years, and for the first time, the option of interacting with a hypersegmented media offer and in tune with their cultural identity in an easy and economic way, if they decide to do so.

The digital transformation has altered the communication scenario in recent years. This change has forced the traditional media to modify formats, contents, editorial lines and distribution and consumption processes in order to reach a more demanding and volatile user. Given this contextual transformation of the sector, how has that change affected ethnic media and migrant communities?

After the digital revolution, migrant communities have a larger number of communication resources available to get the information they need, to get visible as a group and to build their own identity within the host societies. Melella (2013) points out that ICT, especially those tools related to Web 2.0 (social networks, blogs, wikis) together with the digitization of numerous traditional media, have transformed the reality of the ethnic press that is published through the internet. The Internet offers migrant groups the possibility of accessing, at a low cost and immediately, a large number of contents specifically aimed at them.

In recent years, digital media, web pages, streaming channels, Facebook spaces or blogs aimed specifically at migrants have proliferated. In turn, some traditional ethnic media have had to adapt to the new market rules by joining the use of digital ICT. For example, large television chains such as Televisa or Telemundo broadcast their contents on Facebook pages or Youtube channels among thousands of followers who, in turn, make them viral in other spaces of the network. Though the digital divide and access to connectivity have not yet been completely reduced, entire communities that had remained far from the media circuits enthusiastically join information consumption through the network. The set has allowed a multiplication of possibilities articulated around two main needs: direct contact around virtual spaces of migrants and their families and establishment and strengthening of communities linked by an identity factor.

On the other hand, the boundaries between traditional and digital media have blurred over time. As Castells (2009) points out, we have gone from mass communication to “mass self-communication”, in which the receiver can build his own informative offer on demand. Along with this multiplication of the offer, the passage of ethnic media to the online format has presented two other fundamental advantages for their users: lower prices and ease of access. The combination of these two factors has led to a considerable improvement in terms of costs and distribution for those media that had to target a fragmented, sometimes scattered audience.

The new online social communication channels, associated with Web 2.0 such as social networks, blogs, wikis and interactive games, have meant an update of the functions of traditional ethnic media. The online ethnic communities have, in many cases, taken the baton as solidarity channelers and group identification, as well as cultural connectors between migrants and their countries of origin.

Their new technological characteristics cause online ethnic media to provide different functions from the analog ones: first, the characteristic interactivity of the internet causes them to be more decentralized and democratic than analog ethnic media (Georgiou, 200 5). With the elimination of physical and geographical barriers, the network has allowed online interactions to reach a transnational dimension based on immediate exchanges among users from different countries, something difficult to achieve in the traditional analog format.

While, in the analog media, the producer and the public are separated and their structure inserted in corporations guided by financial interests, online ethnic communities, such as blogs, forums or social networks, tend to be less restricted by these conditions. This offers several advantages for their users: on the one hand, a greater openness to public discussions, more possibilities to develop a sense of group belonging through user-to-user interactions and, finally, the option for the group to become creators or diffusers of informative content, whether original, curated or shared, unlike the traditional model in which these users had a role of passive receivers. In this line Melella (2016) cites the work of Karim (1998) to illustrate how many migrants already used traditional media for years (newspapers, magazines, radio or television) to inform, entertain and connect with their community of origin, However, the emergence of ICT allows them today to expand and extend these communication activities on a much more global scale.

In many cases, the transition from analog to digital is given by ethnic media and their audiences in a totally natural way. Already at an earlier stage of the digital ecosystem, Shi (2005) pointed out that members of the Chinese diaspora did not change their news sources when connecting online and chose to follow the same Chinese newspapers that they read on paper.

The trend seems to indicate that ethnic media are following the digitizing process at a similar rate as generalists, but taking advantage of the uniqueness of addressing niche audiences that, in the case of the former, reach a competitive advantage, in an era where ICT facilitate cultural and affinity segmentation. According to a study by Matsaganis (2016) focused on one of the cities that has a greater degree of multiculturalism like New York, 90% of the city’s ethnic media had created a web page; 82% of them distributed their contents through social networks, mainly Facebook and Twitter; and 30% had created a specific application for their readers to download their contents. 46% of the ethnic media participating in that study admitted sharing their posts on Facebook at least once a day.

In general, the online space has allowed the media to distribute their contents in a faster, more segmented and more economical way, in addition to maintaining closer contact with their readers. Their dynamics allow them to produce new stories easily following the interests of their audiences, obtain feedback on those that are already being produced and access new market niches, especially among digital natives.

5. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

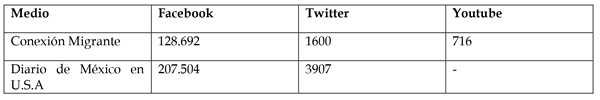

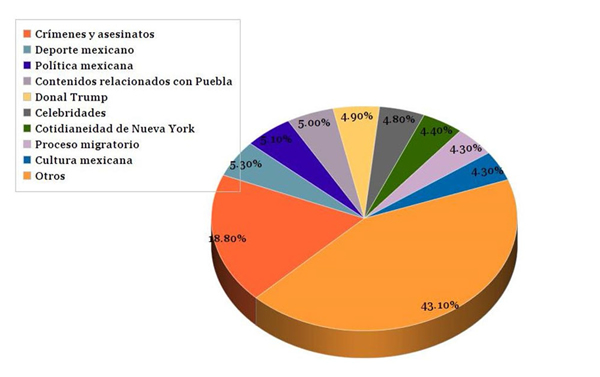

It is important to note that the influence of social networks on traditional media has caused a much more horizontal and participatory conception regarding the generation of contents and news. A member of a community on Facebook or any Twitter user has the option to alert about any current events that are occurring at that moment in real time, which provides abundant clues to journalists of each media about what their audience wants. Concerning the two cases we studied, both Migrant Connection and Newspaper of Mexico in USA have presence on Facebook and Twitter and a large virtual community. Migrant Connection also has a YouTube channel in which its videos are close to half a million views.

Table 1: Virtual community of both media studied.

Source: Own elaboration based on data in networks as of April 16, 2019.

Together with social networks, the use of complementary ICT, such as Skype, WhatsApp or programs for online collaborative work are making it possible to organize transnational newsrooms and work teams much more easily. The relocation of their audiences is not stranger to that of the media templates themselves. A newsroom in New York can work remotely with its correspondents in Tijuana or Mexico City with great ease, a situation that affects the line of treated contents, as they acquire a more transnational character, halfway between the society of origin and the host society. For example, Migrant Connection, which is addressed to the global migrant community in the United States, is carried out from Mexico City with specific collaborations and trips to the United States by its editors. For its part, Newspaper of Mexico in the USA, according to its director Germán Baz, has a team of four people in Mexico and two correspondents in the United States. The correspondents are the ones that send and seek raw information, but a consensus about it is previously reached at the newsroom in Mexico, so the contents are sent crude from the US and are used for final delivery in Mexico.

In addition to newsrooms, broadening the base of readers means you can also purchase this transnational bias thanks to digitization. Sometimes, this step to the digital format allows individuals from the country of origin and who intend to migrate to the host society, or simply have a previous interest in it, to access an online, choosing, to get informed, the ethnic media corresponding to their group even if they do not yet reside in it. In the case of Migrant Connection, its director Patricia Mercado makes clear this transnational vocation inherent in its foundation, the digital space focuses on providing practical information (procedures, legislation) to Mexican migrants before they undertake the migration process to the United States.

Another highlight of the advantages of the online format of many ethnic media is that it provides migrants in the diaspora with reference points and common spaces to communicate with people who remain in their country of origin but also with other compatriots in the host country. Old bonds are maintained that unite the dispersed population in the “cultural and transnational” and, at the same time, new links for relationships and social integration. The diaspora constituted by migrants of the same nationality dispersed in several countries thus has the opportunity to integrate into the same virtual community associated with an ethnic environment, either on their Facebook page or through the comments of the news on their site. Thus, the Facebook pages of both Migrant Connection and Newspaper of Mexico in the USA have become virtual spaces of coexistence and opinion for Mexicans on both sides of the border.

If the generalization of the spaces associated with Web 2.0 represented a fundamental change in the conception of ethnic media, the arrival of smartphones has been a second step in terms of digitization, particularly as s consumption habits of its readers, but also in the adaptation of contents. Following the study of Matsaganis (2016), 48% of New York ethnic media adapt their contents to multi-screen formats, which allow easy accessibility from the mobile phone. This is the case of the two media studied in this article, both agree in pointing out that they receive more than half of their web traffic through mobile devices.

The flexibility of ethnic media, in terms of size and location, has taken advantage of the possibilities offered by the digital format for greater audience segmentation. While some of these best known media are large, such as Univision in the United States, or have a transnational character, such as the Chinese newspaper Sing Tao Daily, many are small publications covering cities or even neighborhoods where a particular ethnic community is concentrated. As a result, digitizing them potentiates, as a competitive advantage, the fact that they can provide their audiences with specific content on the immediate area not covered by the mainstream media.

If the transition of these small-sized media to the digital format has advantages over the costs of production and printing, it also involves threats, mainly through the difficulties to gain visibility in communities not so computerized and where a newspaper is not distributed door to door any longer.

5.1. The geo-ethnic approach to media contents

The news and events that allude today to a local community play a preponderant role between the preferences of immigrants and ethnic minorities. (Matsaganis et al., 2011). Local content in the US ethnic media gains ground among second-generation migrants, and even more so among the third generation. The public that follows these media obtains their reward through the geo-ethnic approach of their narration and contents.

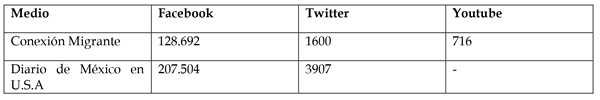

Source: self made through the analysis of a total of 631 publications made by Migrant Connection between 01/01/2018 and 02/24/2018.

Graph 1: Contents of Migrant Connection.

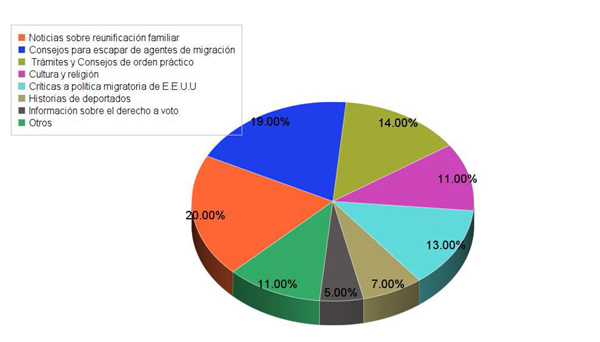

In the case of Migrant Connection, this geo-ethnic approach is focused on keeping the bonds with the country of origin (54%) the daily lives of the migrant community in the United States (46%), when alluding to them, focuses mainly on the problems related to integration in the country and the pressure of immigration authorities on the community. In the case of Newspaper of Mexico in the USA, the publications are already separated on the site by specific thematic blocks, publications related to Mexico represent 51.3% of the total; those related to the Mexican community in New York, 23.6%; while those referring to New York City and the whole United States, only 12.3% and 10.4% respectively.

Source: self-made after analyzing a total of 753 publications by Migrant Connection between January 15 and March 15, 2018.

Graph 2: Daily Contents of Newspaper of Mexico in the USA.

In the digital media context, on many occasions, a relationship of proximity and trust is generated between the producers, journalists, businessmen, community managers of these media and their audiences, since the former are also usually members of the communities of whom they inform. This connection with the local area also encourages direct participation of consumers in the production and dissemination of the contents that feed the newsrooms. In turn, the stories ethnic media deal with are increasingly forced to focus on relevant issues very present in the daily lives of their audiences (Katz, Matsaganis and Ball-Rokeah, 2012). The directors of the two media we studied agree that many reports and ideas for new content come to them by indication of their own readers through social networks or through claims and proposals made by email.

The adaptation to the digital format, however, has also caused some difficulties: On the one hand, the arrival of new digital social media that has led to a diversification in the writing and distribution processes related to the contents. The same news is usually made up of different pieces and adaptations: a text, a photo gallery, audio podcast, infographics, specific contents for applications... However, in many cases, the media cannot offer the audiences of some countries of origin all of those contents due to connection and speed difficulties. Some of them are forced to adapt formats, quality and resolution of many contents to make sure to overcome the difficulties imposed by the digital divide and reach both ends of their transnational audience. For example, a case such as that of the ethnic media Cuban Newspaper is unable to offer exactly the same contents to its readers in Havana and Miami due to access limitations in the territory of origin.

This confluence between new channels and formats used, as noted by Johnson (2010) and Matsaganis (2016), is aimed at attracting 18-29-aged groups and represents a change regarding the traditional segment that traditional ethnic media used to target. The young population group shows the highest frequency of use in social networks. There is where we find the nursery that will allow future audiences for ethnic media to be loyal. Something that is observed with the content policy undertaken by these means or the efforts made to distribute them via new mobile applications.

On the contrary, the digitization of many ethnic media has also led to certain complications related to the digital divide. Problems related to the use, access, design or language used by new tools or public connection policies (Dijk, 2013) often become barriers that prevent migrants from using them. These barriers are noted in those first-generation migrants and an elderly group, who are forced to undertake, at the same time, a double migratory process: physical migration with a new space with the consequent change in terms of the cultural habitus and the migration of media consumption from analog to digital format. In this last journey, the migrant must acquire a new catalog of uses and abilities in order to obtain the information he had been receiving regularly.

Both in the case of Migrant Connection and that of Newspaper of Mexico in the USA, its two directors agree that their readers fall into a profile of first-generation migrants between 18 and 35 years old, without a high level of education. A Spanish-speaking population, still little acculturated, who retains much of its original identity features, as well as interest in preserving them. In many cases, access to ICT by these groups is being carried out at the same time as the migration process.

5.2. New formats same rewards

Without even going into how digitization has affected this process, in the discussion about the effects and utilities of the so-called “ethnic media” to preserve the cultural identity of migrants in the host societies and provide them with gratifications from the identity viewpoint, there are opposing academic positions.

In the first place, to those who defend their usefulness to favor inter-ethnic communication and group exchange, becoming multiethnic spaces of cultural expression, establishing dialogues between different cultures to empower those minorities. The second option, on the other hand, is represented by those who point out that the consumption of ethnic media by migrant communities leads to a “group withdrawal” and a delay in the integration process. The two visions coincide with two different approaches to the process of integration of migrant communities in a given host society; as are the assimilationist and the multiculturalist.

In the first group, Viswanath and Arora (2010) assign to these channels a fundamental responsibility in the success of the integration of a community in a new country, by providing general information, discerning rules and decoding new indigenous cultural symbols for newcomers. On the other hand, Johnson (2000), Houssein (2013) and Ramasubramaniam et al. (2017) defend that ethnic media play an important role in the life of migrant groups, covering, on the one hand, their need for entertainment, but also for information, and maintenance of their cultural identity.

This line about the positive effects of ethnic media from the point of view of integration would be stressed by Mendieta (2009). His research focuses on analyzing, from the Spanish context, how these channels would favor the inclusion of migrants, by standing up as speakers of their daily reality, providing them with information and, as a consequence, encouraging their civic participation in the host society. In the face of the generalist media, these channels would offer information focused on the reality of their first steps in the migration process without damaging their integration dynamics.

On the other hand, Riggins (1992) justifies the usefulness of ethnic media as simple tools at the service of the survival of certain minorities in multicultural societies. The existence of ethnic channels would also be useful for the host State as it would, in many cases, favor the survival of these media due to their effectiveness in monitoring minorities that may be problematic, in addition to providing important information to those groups that still do not master the language of the host country. Into these utilities does one of the cases studied in this article clearly fall, such as the Migrant Connection aimed at providing practical information to Mexican migrants who have undertaken the migration process but do not speak English yet.

There are discordant voices regarding this vision of ethnic media as facilitators of integration (Jeffres, 2000; Shi, 2009; Penalva and Brückner, 2008). Away from purely integrative perspectives in the host society, ethnic media offer minority communities other kinds of utilities and rewards: For example, the opportunity to offer a vision of themselves and build positive images that counteract those that might be loaded with stereotypes by the generalist press (Georgiou, 2005 and González Aldea, 2012).

This function is effective as long as ethnic media use the predominant language in their host country, otherwise, representations in the majority society will be limited. Another characteristic feature of ethnic media would be that of acting as “sentinels,” warning their readers about external threats and changes, warning about crimes against immigrants and changes in immigration laws (Viswanath and Arora, 2000). In the case we are dealing with in this article, the arrival of Donald Trump to power in the United States and the persecution of illegal migrants in Latin America as one of the axes of his policy would have reinforced this role of ethnic media as sentinels.

In this context, Latino media have been involved in their awareness and denunciation work, work that has increased efficiency by channeling these protests through various online channels such as social networks. Both Migrant Connection and Newspaper of Mexico in the USA devote a significant space in their contents to Donald Trump and his immigration policy (13.9%) and (9.7%) respectively.

Sometimes, the ethnic press appeals to very specific cultural communities that have chosen a certain degree of isolation. The ethnic environment tends to reinforce that isolation by exploiting it in its content line as a business model. Penalva and Brückner (2008) study a representative case from the weekly CBN, aimed at Germans residing in Spain, this weekly works as a mediation model focused only on users and their cultural interests, trying to connect with the reality of the audience above the points in common with the environment in which they are inserted. Although not so significantly, the two media we studied dedicate a large part of their contents to those aspects related to Mexican culture and politics (17%) in the case of Newspaper of Mexico in the USA and 13% in the case in Migrant Connection, favoring mainly in its line of contents those who have to do with aspects of their own migrant community.

Some research (Viswanath and Arora, 2000; Johnson, 2010) indicates that, when minority audiences have a wider range of media, they prefer those produced by and for their group. The origin of these preferences would be in the perceptions of migrants about the ethnolinguistic vitality of their community and their role in their host society. In both perceptions, the role of ethnic media and the vision they offer as reinforcers of their culture would take part. In this line, Abrams and Giles (2009) show how television consumption by Latino migrants in the United States offers a correlation between the level of ethnic identity and vitality as well as between the level of group identification and the consumption of ethnic press. The consumption of generalist media reminds many migrant communities of their low social status while the ethnic press produces the opposite effect; an identity gratification through evident reinforcement of their self-esteem.

Among the relevant functions these spaces fulfill is that of being the archive of cultural memory. A report that expands its possibilities through the online environment. Houssein (2013) explains how the traditional ethnic press used by Somalis in Canada, mainly radio programs, and digital media, through YouTube videos, would work through a message selection as a form of multimedia commitment. That commitment would extend the longevity of some of their traditions such as language, Somali poems or songs, shared as a family at home and explained from parents to children, but integrating other aspects of the host society in which they live.

The emergence of new virtual spaces such as Facebook groups and pages, online forums or YouTube channels favors, through interactive, lattice and non-hierarchical structures, the exchange of content previously selected to exercise that memory preservation function. In them, the society of origin is usually recreated in an idealized way through the use of nostalgia. Spaces dedicated to cooking recipes, song reminders or explanation of religious traditions are recurring especially in the Migrant Connection portal, fulfilling that function of memory preservers for migrant groups the ethnic media have traditionally fulfilled but adapted to the interactive and viral possibilities offered by ICT.

In any case, it seems clear that digitization provides both media and new users with possibilities when undertaking together a process of identity reconstruction. Those ethnic media that have adapted to new virtual spaces to link new and old cultural uses and identities and consumption habits are taking advantage of them. To Yin (2013), cyberspace, instead of dissolving identities, sometimes helps reinforce them. In this digital space there are still more and more specialized media, such as ethnic media.

Ethnic media do not necessarily have to build a country other than that of the host society, but they do more easily establish a bridge for new migrants, who often continue to be ignored by the generalist media. Their role continues in force, reinforcing a sense of group belonging to a de-territorialized group and its members in the diaspora.

From the content line, it can also be perceived whether the medium in question is more focused on strengthening bonds with the country of origin and structuring group identity than on establishing connections with the host society. In that sense, as we have already pointed out previously, the concept of “Geo-ethnic Storytelling” coined by Lin and Song (2006) is interesting, according to which ethnic media can privilege the contents that affect the ethnic community they target to a greater or lesser degree, as we have seen in the two cases chosen for this article, in the face of the possibility of choosing a line based on the central affairs of the host society.

The geo-ethnic narrative would be based on two main lines of content: first, stories that are ethnically or culturally relevant to a particular ethnic group (immigration policy, threat from the Trump’s administration, racism cases) and second, stories that are geographically linked with the events unfolding in the countries of origin (elections in Mexico, Mexican culture and sports) and, at the same time, by focusing on the political, social and legislative situation of a particular community, they can get involved, through their themes, in strengthening the work of civic awareness.

But how would the incorporation of ethnic media into the digital space have affected when continuing to favor assimilation in the host society or maintaining their identity characteristics?

5.3. Digital spaces and mobile identities

From the point of view of the consumer, despite the different speeds of migrants regarding their incorporation to the use of ICT according to their degree of digital literacy, overall, it can be said that this is occurring without very significant differences between migrants and the rest of the population. Various spaces and digital platforms, among which ethnic media are located, would be playing a role as new ways of enduring the distances and the consequent longing for them, as well as participating in the ancient daily reality. As Peñaranda (2011) points out, to leave a place does not mean to stop “being or leaving altogether”. That is, ICT allow many migrants to participate in the public, domestic or family life of the place that has been left behind.

The cases of migrants who, through Facebook pages or other virtual spaces dedicated to their locality of origin, continue to be in contact with their family and neighbors or remain informed of the latest news are habitual. The development of the digital landscape allows many transnational migrant families spread over several countries to access the same contents and share a virtual space that, on many occasions, is to be an ethnic environment, mainly through its site or social networks. Thus, a medium conceived with a transnational vocation such as Migrant Connection is a clear example of how these spaces can become a bridge between migrants on both sides of the border through which to exchange information, experiences, memories and redefine the migratory experience of migrants and their families.

As a whole, digital transformation, far from ending the ethnic media, has reinforced their role as a main source of training for many migrant communities vis-à-vis the generalist media. In the context of a multimedia environment, ethnic media, with their contribution, contribute to creating a multicultural sphere and nourish the dispersed diaspora by offering opportunities to interact in increasingly distant realities. At the same time, it could be argued that they promote the risk, as Luo (2016) points out, of an excessive communicative location that can end up isolating a particular society in ethnic enclaves by fostering their segregation. Migrants take advantage of the segmentation of new digital media (Brantner and Herczeg, 2013), moving away from the public space provided by the host society to focus preferably in interacting with contents and users from the society of origin.

In relation to this possibility, already at the end of the 20th century Gitlin (1998) predicted a scenario in which the public sphere would be replaced with public spheres through which minorities would articulate their decision and information spaces through transnational networks based on their cultural connection These small “spheres” would respond better to their needs and interests in the face of the great and rigid public sphere of nation states, in which loyalty is, in many cases, a previous prerequisite for migrants’ identity assimilation.

In part, thanks to the development of ICT, today the migrant lives his diasporic reality as a multiple position in various symbolic and geographical spaces. Within this reality, identity feelings continue to weigh on the possibilities of choice. Ethnic media with their massive incorporation into the digital ecosystem have found a way to reach their communities and market niches through microlocal contents that explode more easily than from the analog format, very specific belonging features associated with identity: language, race, place of origin, gastronomy, music...

The great mobility and the increase in the mediation offer cause many people to be living in what Georgiu (2010), citing Beck (2002), suggests in a suggestive way as “polygamous space”. This space is characterized by great mobility and greater mediation by the subjects, which causes more and more people to be influenced and, in many cases, to have at the same time feelings of identity belonging to different places and cultures. The technological and media availability favor simultaneous and immediate access to these distant worlds, which ends up defining their belonging to a specific community crossed with their insertion into globality.

Finally, as it has been pointed out in this article, the relations that migrants develop or maintain in the diaspora with their family and group of friends are increasingly interconnected and mediated, making the territorial particularity less significant and communication spaces more relevant when configuring their identity and belonging. That context influenced by new forms of production and consumption in urban areas could act also diluting connections to the country of origin in the long term. Thus, the identity construction of a Mexican in New York can make, in many cases, depending on their media consumption, more sense than that of a “US Mexican”. By having access to a wide range of media and communication technologies on the network, the subjects of the diaspora can control the way in which individuals and communities connect or disconnect “on demand” either in their nearby neighborhood or in very distant places, articulating, if they so wish, their condition of identity belonging more and more individually.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The ethnic media are following the process of digitization at a similar rate as the generalist media, but taking advantage of the uniqueness of addressing niche audiences where cultural segmentation and affinities predominate, which has opened up new business opportunities. On the other hand, digitization has meant a considerable improvement in costs and distribution for ethnic media. Traditional large ethnic media use the new social channels to increase their audiences, spread their contents by gaining in viralization and reach, while the small ones have managed to penetrate specialized niches by exploiting identity links and a focus on content proximity.

As those responsible for the two cases we studied have pointed out, the transition to the digital format has also allowed ethnic media greater delocalization of their newsrooms by increasing the possibilities of informative immediacy not linked to geographical proximity, as well as a greater participation of their readers in the elaboration of the contents and a continuous feedback. In the same way, the new technological characteristics cause the online ethnic media to provide different functions from the analogs ones: greater interactivity and decentralization that result in the elimination of geographical barriers and the scope of a transnational dimension based on continuous interactions of user to user breaking geographic barriers. Finally, as happens in “Migrant Connection” that users have the option to get involved in the media by becoming creators or disseminators of informational content.

The study of the two proposed cases selected in this article, despite not representing a significant sample to confirm that virtual ethnic media have taken the baton of most of the functions performed by traditional ethnic media, makes it possible to glimpse that they continue to perform some of them: either as identity gratifiers, reinforcers of the feeling of belonging, preservers of memory and cultural tradition or sentinels against external threats to the migrant community they target. Through the analysis of the contents and the editorial policy conducted in this piece of research, it is evident how the arrival of Donald Trump to power in the United States and the persecution of illegal Latino migrants as one of the pillars of his policy would have reinforced that role of sentinels of the two ethnic media we studied. Both Migrant Connection and Newspaper of Mexico in the USA dedicate a significant space in their contents to Donald Trump and his immigration policy.

On the other hand, the reinforcement with tools such as Facebook pages, online forums or YouTube channels favors, through interactive, reticular and non-hierarchical structures, contact and recreation by migrants from the home society. ICT today allow many migrants to participate in the public, domestic or family life of the place that has been left behind. In the same way, they provide rewards related to the preservation of memory and group cohesion but adapted to the viral and interactive possibilities offered by ICT. The home society tends to recreate itself through the use of nostalgia. Both in “Newspaper of Mexico in the USA” and “Migrant Connection”, especially in the latter, there are frequent spaces dedicated to cooking recipes, song reminders or explanation of religious traditions.

According to several authors Lin (2013), Luo (2016), the new digital media make it possible, through hypersegmentation according to interests and the multiplication of communicative interactions away from the public space offered by the host society, to focus preferably on interacting with contents and users from the home society. The two ethnic media studied for this chapter would be privileging those bonds over those related to the host society through various dynamics: privileging bonds with Mexico in their content line over information related to the United States, publishing all information in the language of the society of origin or reinforcing the feeling of otherness through editorial lines that underline the persecution they suffer as an ethnic minority. However, the technological and media availability inherent in the network also favors simultaneous access to different identities “a la carte”, which portends that, in the long term, it also fractures feelings of belonging, increasingly related to hybrid identities that are inserted into globality.

REFERENCES

1. Abrams, J. R. & Giles, H. (2009). Hispanic television activity: Is it related to vitality perceptions? Communication Research Reports, 26(3), 247-252. doi: https:// DOI.org/10.1080/08824090903074456

2. Brantner, C. & Herczeg, P. (2013). The life of a new generation: Content, values and mainstream media perception of transcultural ethnic media – an Austrian case. Communications, the European journal of communication research, 1, 65-81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/commun2013-0012.

3. Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

4. Dijk, V. J. (2013). A Theory of the Digital Divide. The Digital Divide. In M. Ragnedda, & G. W. Muschert (Eds.), The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective (pp. 29-51). New York: Routledge. Retrieved from https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/a-theory-of-the-digital-divide

5. Georgiu, M. (2005). Diasporic media across Europe: Multicultural societies and the universalism– particularism continuum. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(3), 481-498. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/95639.pdf

6. Georgiu, M. (2010). Identity, Space and the Media: Thinking through Diaspora. Revue européenne des migrations internationales, 26(1), 17-36. Retrieved from https://journals.openedition.org/remi/5028

7. Giménez, G. (2012). La cultura identidad y la identidad como cultura. Ponencia inédita. Instituto de investigaciones sociales de la UNAM. Recuperado de http://perio.unlp.edu.ar/teorias2/textos/articulos/gimenez.pdf

8. González Aldea, P. (2012). Romanian ethnic media in Spain: Self-representation of immigrants in the public sphere. Paper presented at the CEE Communication and Media Conference. Prague, Czech Republic. Retrieved from

9. https://www.academia.edu/2081362/Romanian_ethnic_media_in_Spain_the_self-representation_of_the_immigrants_in_the_public_sphere

10. Houssein, C. (2013). Diaspora, Memory, and Ethnic Media: Media Use by Somalis Living in Canada. Bildhaan. An International Journal of Somali Studies, 12(11), 87-105. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/bildhaan/vol12/iss1/11

11. Jeffres, L. (2000). Ethnicity and Ethnic Media Use: A Panel Study. Communication Research, 27(4), 496-535. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/ DOI/pdf/10.1177/009365000027004004

12. Johnson, M. (2000). How ethnic are US ethnic media: The case of Latina magazines. Mass Communication & Society, 3(2-3), 229-248. doi: https:// DOI.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0323_04

13. Kanellos, N. (2000). A brief history of Hispanic periodicals in the United States. En N. Kanellos & H. Martell (Eds.), Hispanic Periodicals in the United States: Origins to 1960 (pp. 3-142). Houston: Arte Público Press. Retrieved from http://docs.newsbank.com/bibs/KanellosNicolas/Hispanic_history.pdf

14. Karim H. (1998). From ethnic media to global media: Transnational communication networks among diasporic communities. Retrieved from http://www.transcomm.ox.ac.uk/working%20papers/karim.pdf

15. Katz, V., Matsaganis, M. & Ball-Rokeah, S. (2012). Ethnic media as partners for increasing, broadband adoption and social inclusión. Journal of Information Policy, 2, 79-102. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jinfopoli.2.2012.0079

16. Luo, L. (2016). Digital Ethnic Media: Integrating Minorities and Connecting Diversities - Digital Diaspora, Virtual Diaspora Community. Tesis Media and Communication Studies Department of Communication and Media. Lund University, Sweden. Recuperado de http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8872748&fileOId=8881906

17. Matsaganis, M.; Katz, V. S. & Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (2011). Understanding Ethnic Media: Producers, Consumers, and Societies. Los Ángeles: Sage.

18. Matsaganis, M. (2016). New York Ciy´s ethnic media in the digital age. Center for commnunity and ethnic media. University at Albany. Recuperado de https://voicesofny.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/NYC-Ethnic-Media-in-the-Digital-Age_Matsaganis_Presentation-Slides_12082016.pdf

19. Melella, C. (2013). Del inmigrante desarraigado al migrante conectado. La construcción de identidades de los colectivos andinos en la Argentina a través de la Web. VII Jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores. Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. Recuperado de https://www.aacademica.org/000-076/22.pdf

20. Melella, C. (2016) El uso de las Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación (TIC) por los migrantes sudamericanos en la Argentina y la Conformación de redes sociales REMHU. Rev. Interdiscip. Mobil. Hum 24(46), 77-90. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1980-85852016000100077&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es

21. Mendieta, A. M. (2009). Papel de los medios de comunicación y las nuevas tecnologías en el apoyo a las identidades étnicas y en la integración de las minorías en las sociedades de acogida. El caso de España. En M. C. Blanco e I. Barbero (Coords.), Pautas de asentamiento de la población inmigrante: implicaciones y retos socio-jurídicos (pp. 249-266). Madrid: Dykinson.

22. Penalva, C. y Brückner, G. (2008). Comunicación intercultural. Un estudio de caso sobre la prensa local extranjera en España. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 66(50), 187-211. doi: http://revintsociologia.revistas.csic.es/index.php/revintsociologia/article/view/101/102

23. Peñaranda, M. C. (2011). Migrando en tiempos de globalización: usos de tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en contextos migratorios transnacionales. F. García y N. Kressova. Actas del I Congreso Internacional sobre Migraciones en Andalucía (pp. 2023-2032). Granada: Instituto de Migraciones. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4050071.pdf

24. Ramasubramanian, S., Doshi, J. & Saleem, M. (2017). Mainstream Versus Ethnic Media: How They Shape Ethnic Pride and Self-Esteem Among Ethnic Minority Audiences. International Journal of Communication, 11, 1879-1899. Recuperado de http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6430

25. Riggins, S. H. (1992). The Media Imperative: Ethnic Minority Survival in the Age of Mass Communication. In S. H. Riggins (Ed.), Ethnic Minority Media: An International Perspective (pp. 1-20). London: Sage Publications.

26. Rodríguez, I. (2008). El valor de la investigación histórica para la teorización sobre la prensa étnica en los Estados Unidos: El caso del periodismo español en Nueva Orleans. Razón y Palabra, 13(63). Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199520798022

27. Shi, Y. (2005). Identity Construction of the Chinese diaspora, ethnic media use, community formation, and the possibility of social activism. Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 19(1), 55-78. doi: https:// DOI.org/10.1080/1030431052000336298

28. Shi, Y. (2009). Re-evaluating the alternative role of ethnic media in the US: The case of Chinese language press and working-class women readers. Media, Culture and Society, 31(4), 597-616. Recuperado de http://journals.sagepub.com/ DOI/abs/10.1177/0163443709335219

29. Viswanath, K. & Arora, P. (2010). Ethnic Media in the United States: An Essay on Their Role in Integration, Assimilation, and Social Control. Mass Communication and Society, 3(1) 39-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_03

30. Yin, H. (2013). Chinese-language Cyberspace, homeland media and ethnic media: A contested space for being Chinese. New Media & Society, 17(4), 556-572. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813505363

AUTHOR

Enrique Vaquerizo Domínguez: He has a PhD in Audiovisual Communication from the Complutense University of Madrid and a Degree in Journalism and History from the University of Seville; he works as a journalist and consultant for Social and Corporate Communication as well as a professor of the Master’s Degree in Political and Institutional Communication at the Camilo José Cela University. He has published articles in national and international journals and has participated in various collective books, congresses and conferences related to the topics of migration, communication and ICT.

enrvaque@ucm.com

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4146-9900

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=yy9GQ6wAAAJ

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/EnriqueVaquerizoDom%C3%ADnguez