10.15178/va.2019.148.101-119

RESEARCH

THE SPEECH REFERRED TO IN THE OPINION ARTICLES. ANALYSIS OF DIALOGUE IN THE COLUMNS OF ALFONSO SÁNCHEZ

EL DISCURSO REFERIDO EN LOS ARTÍCULOS DE OPINIÓN. ANÁLISIS DEL DIÁLOGO EN LAS COLUMNAS DE ALFONSO SÁNCHEZ

O DISCURSO REFERIDO NOS ARTIGOS DE OPINIÃO. ANALISES DO DIÁLOGO NAS COLUNAS DE ALFONSO SANCHEZ

María Ángeles Villa García1

Licenciada en Periodismo en la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia. Actualmente realiza el Doctorado en la Universidad Católica de Murcia, en el programa de Ciencias Sociales. Editora de informativos en la Televisión Autonómica de Murcia.

Enrique Arroyas Langa1

1Catholic University San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), Murcia. Spain

ABSTRACT

Polyphony is a characteristic feature of journalistic discourse. Through the representation of different voices, the interpretative and ideological diversity of the social context is introduced. In the discourse the different voices relate to each other and to the voice of the narrator. This work aims to reflect on the dialogue as a rhetorical resource in the opinion article. Our hypothesis is that reported speech is a technique that produces rhetorical effects, which, in the case of opinion columns, contribute to the reinforcement of its persuasive power. Thus the objective of this work is to define and describe the use of reported speech in opinion columns and analyze its aesthetic and cognitive effects. For this purpose, the dialogical components of ten columns written by the journalist Alfonso Sánchez in the Informaciones newspaper will be analyzed, since according to our hypothesis this author picks up the tradition of the article of customs at a moment of renewal of the opinion genre in Spain. The rhetorical and narrative analysis that we carried out shows that Sánchez’s column interprets reality through a polyphony of voices, directed by a narrating self that acts as a witness. Through the opening to the voices of the characters, the discourse referred to increases the dynamism of the narrated facts, provides verisimilitude and, limiting the presence of the narrator, opens the discourse to a plurality of approaches.

KEY WORDS: articles, column, opinion, dialogue, rhetoric, journalism, narrative

RESUMEN

La polifonía es un rasgo característico del discurso periodístico. A través de la representación de distintas voces se da entrada a la diversidad interpretativa del contexto social. Este trabajo pretende reflexionar sobre el diálogo como recurso retórico en el artículo de opinión. Nuestra hipótesis es que el discurso referido es una técnica que produce efectos retóricos que, en el caso de las columnas, contribuyen a reforzar su poder persuasivo. El objetivo es definir y describir la utilización del discurso referido en las columnas y analizar sus efectos estéticos y cognitivos. Para ello se analizan los componentes dialógicos de diez columnas escritas en el diario Informaciones (1954 -1980), por el periodista Alfonso Sánchez, pues según nuestra hipótesis este autor recoge la tradición del artículo de costumbres en un momento de renovación del género de opinión en España. El análisis retórico y narratológico que llevamos a cabo muestra que la columna de Sánchez interpreta la realidad a través de una polifonía de voces, dirigidas por un yo narrador que actúa como testigo. Mediante la apertura a las voces de los personajes, el discurso referido aumenta el dinamismo de los hechos narrados, aporta verosimilitud y, limitando la presencia del narrador, abre el discurso a una pluralidad de enfoques.

PALABRAS CLAVE: artículos, columna, opinión, diálogo, retórica, periodismo, narrativa

RESUME

A polifonia e um traço caraterístico do discurso jornalístico a traves da representação de distintas vozes da entrada a diversidade interpretativa do contexto social. Este trabalho pretende reflexionar sobre o diálogo como recurso retorico no artigo de opinião. Nossa hipótese e que o discurso referido e uma técnica que produz efeitos retóricos que, no caso das colunas, contribuem a reforçar seu poder persuasivo. O objetivo e descrever a utilização do discurso referido nas colunas e analisar seus efeitos estéticos e cognitivos. Para isso se analisa os componentes dialógicos de dez colunas escritas no jornal Informaciones (1954-1980), pelo jornalista Alfonso Sanchez que segundo nossa hipótese este autor continua a tradição do artigo de costumes em um momento de renovação do gênero de opinião na Espanha. A análises retorica narratológica que utilizamos mostra que a coluna de Sanchez interpreta a realidade através de uma polifonia de vozes, dirigidas por um EU narrador que atua como testemunha. Mediante a abertura das vozes dos personagens, o discurso referido aumenta o dinamismo dos fatos narrados, aporta veracidade, limitando a presença do narrador, abre o discurso a uma pluralidade de enfoques.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: artigos, coluna, opinião, retórica, jornalismo, narrativa

Correspondence: María Ángeles Villa García. Catholic University San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), Murcia. Spain mangelesvilla@hotmail.com

Enrique Arroyas Langa. Catholic University San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), Murcia. Spain

earroyas@ucam.edu

Received: 04/03/2019

Accepted: 29/04/2019

Published: 15/09/2019

How to cite the article: Villa García, M. A., and Arroyas Langa, E. (2019). The speech referred to in the opinion articles. Analysis of dialogue in the columns of Alfonso Sánchez. [El discurso referido en los artículos de opinión. Análisis del diálogo en las columnas de Alfonso Sánchez]. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 148, 101-119.

DOI: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.148.101-119

Recovered from http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1167

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Dialogue as a retoretic resource and citations styles

Dialogue is the rhetorical resource that gives voice to narrative figures or characters of a narrative. Among the different expressive modes, dialogue is understood as a narrative segment that gathers the dynamics of the action through the expression of acts of language. In this way, the linguistic facts attributable to the characters are integrated into the story as representations of verbal actions.

The style with which the narrator reproduces the discourse of the characters has been the subject of numerous classifications, with a series of typologies that account for the complexity of this mode of reproduction. With a view to analyzing the aesthetic-ontological value that assists each citation style, we will follow the classification criteria based on how to incorporate the voices of the figures involved in the story, according to Genette’s terminology (1989).

The intervention of the figures in the discourse can give rise to another classification of the type of dialogue according to the intervention of one or more interlocutors (monologue and polylogue), according to the recipient of the enunciation (replicas between the figures themselves - interlocutor vector -, towards external figures to the narrative - diverted vector - or to anyone in particular -soliloquy- with the aim of making a thought known) and according to its function (interactive - it advances the story- and narrative - narrate extra-stage events, of the past, or of the future, and therefore introduce a story into the story).

As citation styles, the theory also distinguishes between speech acts and thought acts. This is, however, a peculiarity of the fictional narrative that, a priori, would be beyond the margins of journalistic discourse. In any case, as a resource that fictionalizes the discourse, it can also be considered in the analysis of journalistic texts. García Landa (1998) exposes the different forms that the narrator has of capturing the verbalized inner world of the characters: indirect thinking, as a form of citation of a character’s thinking by the narrator that allows him to explore his conscience and therefore deepens in his motivations with great analytical insight; indirect free thinking, where the difference between spoken word and thought word is diluted with the absence of introductory verbs; direct thinking, as a transposition of the character’s mental activity in direct style; the monologue, like the thought of a character clearly differentiated from the narrator’s speech; and the soliloquy, as a combination of inner monologue and colloquial narrative discourse where the communicative situation is simulated, a meditation out loud without a clear interlocutor.

The communicative and narrative effects of each of these ways of citing refer to the intrusion into the intimacy of the character, his expressive autonomy or the intervention of the narrator. Dialogue is the clearest form of direct or restored referenced speech in which the character’s words differ from the narrator’s speech since they are introduced by two points, hyphens, with or without interpolations of the narrator. They usually also include deictics or adverbial phrases that indicate the character’s time. The narrator’s intervention is limited to selecting the words, limit them and enter them without manipulating the aforementioned speech, and thus the speech of the character and the narrator are separated.

In journalism, dialogue is a predominant way of citing interviews, while in other informative genres, the direct style is preferred, but without the introduction of scripts or linguistic marks, so that the speeches of the different voices are juxtaposed through the period, but with a clear distinction between the two for the reader. Quasi-direct discourse, or mixed style, also abounds, with a syntax characteristic of direct free style, but with marks such as quotation marks that differentiate the character’s words. In the latter case, the subject of the statement transmits the character’s speech trying to preserve the objectivity of the citation with a combination of direct speech and indirect speech that is clearly detectable by the recipient. The character’s words are syntactically integrated into the narrator’s speech, but differentiated through the quotes. As a form of appropriation by the narrator of the enunciation of others, intertextuality can also be considered, when a foreign text is integrated into the discourse itself through citation (Molero de la Iglesia, 2004).

1.2. The effects of dialogue: referential function and truth

One of the aspects of which literary theory has been most occupied is the relationship between text and reality, the problem of representation, which in the case of journalistic discourses takes on a special importance as it is a type of text in the that the realistic contract between author and reader is fundamental, because beyond the theoretical debate on what is the real reference in literature, journalism starts from the premise that its purpose is to talk about the world.

The theory of linguistic functions of Jakobson (1984) concluded that every text fulfilled a variety of functions, between poetic and referential function, and that the predominance of one over the other could serve as a criterion for the identification of genres: while in literature the poetic function was dominant, in journalism the referential or denotative function prevails. The literary theories more in vogue at the end of the last century marginalized in the narrative analysis everything that concerned semantics, the representation of the real and the description, since the idea of the radical disconnection between literary text and the world was assumed. The crisis of ‘mimesis’ reduced the issue of representation to the plausible, a code accepted by the reader, an illusion (Compagnon, 2015).

This distrust of the ability of words to capture the real also reaches journalism, an area that since the second half of the last century has seen how its discursive conventions have been called into question until they give rise to a mixture of genres that, in their most controversial moments, has led to confusion with fiction. Just as the formalists and structuralists considered language as a prison (Jameson, 1980), the authors of the linguistic turn denounced journalism as a trap (Burguet, 2008, Chillón, 2014). It went from an objectivist journalism based on an innocent confidence in the representation of the real to a skeptical journalism that put under suspicion any representation of the real and reduced everything to subjective interpretations (Arroyas, 2009).

However, what was an accessory for literature in the case of journalism remained a basic criterion in the search for the veracity of its texts. It is a debate that is still alive in the theoretical discussion and offers interesting arguments for narrative analysis. Although realism was considered a simple convention, it was studied as a formal effect. As Compagnon (2015, p. 128) explains, although literature cannot copy the real, it is still capital to study how it makes us believe that it copies the real. This approach was also valid for a journalism involved in the linguistic turn and the crisis of objectivity.

Among all the rhetorical resources aimed at reinforcing the referential function of the texts, the referred discourse occupies a prominent place. The plausible as a substitute for the realistic acts as a referential illusion. Although the real thing is not copied, the text could not help being convincing for the reader. What happens is that the reference is not the distant and unattainable reality (in journalism the uncertain truth of the facts could be said) but an intermediate reality, other visions about the real, other texts, intertextuality and, in the broadest sense given by Bajtin (1989), dialogue, concepts that are very clarifying about the scope of texts, both literary and journalistic, and therefore also of journalistic-literary texts, as is the case with opinion columns. Bajtin interprets a text as a complex structure of voices, reality, history and society. This approach is very opportune for the analysis of the journalistic text because it acts as a relation of texts, voices, quotes in an interpretative framework on the real thing whose addressee is a reader, with whom a sense is constructed referring to the real world, an approach, also, that in the case of opinion genres such as the column can contribute to the study of narrative resources for persuasion in a type of text that has literary features.

1.3. Dialogical and polyphonic character of the articles: perspectivism and multifocality

Both intertextuality, a fundamental resource in journalism that aims to account for what happened and that largely refers to pre-existing verbal and textual acts, such as the discourse referring to speech and thought acts are elements that shape the dialogic and polyphonic character that has stood out as constitutive of narrative genres (Bakhtin, 1989, Reyes), but also of journalistic discourse, where the concurrence of heterogeneous voices, as a way of representing different points of view, is part of its method of interpretation of reality (Fernández Lagunilla y Pendones, 1993, Amado, 2014).

A narrative can have several narrators based on their participation in the story, the number of stories that are told and the role that each narrator plays in them. In this way, the dialogue multiplies the number of stories that are told in a narrative by turning a figure into a narrator, what is called a figural narrator, a narrator who has the peculiarity of living the circumstances that he tells from within the story (Spang, 2009). Thus, the first effect of the dialogue is the dramatization of the narrative, which is made more complex by the multiplication in the story of figures, stories, time and space.

From here, it is interesting to analyze, from the point of view of fictionalization, truthfulness and credibility, the relationship between the main narrator and figural narrators of dialogue: if their knowledge is the same as that of the characters so if he knows more or less, then his omniscience or equiscience will have plausibility effects. As a creative space for narrative instances, the referred discourse has a double face: an effect of fictionalization as well as of likelihood. The fictionalization consists of “the expression of figurative, spatial and temporal elements apt to illustrate and make the problem and the subject understandable and, therefore, the message in both ways. And ultimately to make the being transparent, to discover the one, the true and the good in certain circumstances built on purpose by the author” (Spang, 2009, p. 224). However, to the extent that a figure becomes narrator of his own story first a person is also an effect of verisimilitude.

On the other hand, the use of narrative perspectivism and of the expressive and descriptive multifocality as a technique used in the elaboration of the articles expands the psychological and characteristic complexity of the story and brings it closer to the reader. The dialogue has the effect of highlighting the immediacy of events. By opening the voices of the characters, the referred discourse increases the dynamism of the events narrated. In this way, it brings credibility by adjusting to the rules of human behavior. There is a playful dimension in which the actors play a role in order to create the illusion of reality. “The drama can be understood as a playful-existential experiment in which the illusion of reality is created” (Spang, 2009, p. 191).

Finally, dialogic perspectivism also contributes to opening the narrative to a plurality of approaches by verbally exchanging the characters as a way of limiting the presence of the narrator, who goes to the background to create the effect that he is not above his readers and the illusion of not imposing his views as a narrator.

1.4. The dialogue in the article of customs

Dialogical perspectivism was an essential element in the article of customs and thus has been studied in Larra’s work, which stands out for its ability to reflect the various approaches and multiple perspectives in the presentation of the facts through the dialogue of the characters. With this juxtaposition of the opposite perspectives, Larra offers the public “what is known to all but with a new point of view. As a good traditional writer, our author pretends to be surprised by everything that surrounds him, he considers himself a naive inhabitant of a country whose customs he pretends not to know to appear as a foreigner in his own homeland. His success in the fiction of surprise, his rediscovery of what is already known allows him to censor some of the vices of the society in which he lives, while he suggests possible solutions” (Cantero, 2011).

The article of customs is situated in a liminal position between journalism and literature, between factual and fictional narrative. In this sense, it can be considered an intergender, since it was established in the first decades of the 19th century as a form that shares both characteristics typical of various journalistic genres and others exclusive to literary genres, ending up being erected, once institutionalized in cultural practices of the time, as an autonomous genre in its own right (Peñas, 2014).

Towards the end of the 19th century, the article reduced the dimensions it had in the romantic stage and acquired a more journalistic air: direct opinion on current affairs predominated in it. Later he would take on the character of a brief and elaborate text that he has in the contemporary press. Understood in its aspect of endogenous journalistic genre (Peñas, 2014), it is formally developed by virtue of purely media needs; The press provides an expressive support or channel and imprints certain conventions - shortness, thematic condensation, dialogue and actuality. At the same time, it slides into the domains of literature in its desire to display an imaginary discourse, with minimal plots, invented characters, literary techniques and styles, hence the importance of considering this article in its historical-literary genesis. This type of article is reality and imagination with a critical and acute vision of human life; with a little philosophy and a few drops of humor (Martín Vivaldi, 1993).

On the other hand, in the articles of customs there is a clear will to show reality as it is. At the same time that they elaborate a critique of customs grounded in social analysis, they reflect in their texts the objects of their observations with realism, hence that the tradition has always been considered an essential precedent of the subsequent aesthetic movement of realism. According to Peñas (2014), the article of customs agreed well, by its own generic nature, with this desire to bring literature to the public, since the roots and traditions of society, the particular uses and customs are thematically appealed and privative of the Spanish people, thus strengthening a powerful emotional bond with the public, whose portrait was intended to reflect.

The article of customs used to contain a minimal fiction with a narrative that involved a basic moral discourse. The tradition then clashes with a flagrant paradox: as the century progresses and the need to paint modern life, to talk about the current, immediate and contemporary becomes more evident, the article moves further away from that purpose, immersed in a spiral by which refers to its own metaliterary and self-reflexive code as well as models that are already in decline.

Joining with the nineteenth-century customs article, the current journalistic chronicle combines, with greater or lesser intensity, the criticism of customs, the ironic note, the satirical dart, the moral reflection and the attentive look that translates, disambiguates, glosses and portrays the trivial, the custom of each day (Peñas, 2014). The modern column inherits and absorbs all those traditions, transforms them and generates its own horizon of possibilities. As a synthesis, it can be said that in the column the literary and customary articulism initiated by Larra, the chronicle and the newspaper article of the sixties and seventies, the rest of the articles of the intellectuals who collaborated in the newspapers in a way more or less frequent and what since the 50s was baptized as a newspaper column, Anglo-Saxon-American-rooted, closely linked to the daily occurrence and more coupled with the news and comment on what was happening (López Pan, 1995, pp. 18-19).

Forneas (2005) assures that “in our days, most of the articles on customs take the form of columns and have been remarkably transformed since, during the first half of the nineteenth century, they were consolidated as a journalistic and literary subgenre”. In this type of texts survive, transmuted, the spirit of the article of customs, the topical note that links with the obsession of the first articulists to capture the contemporary, fleeting and transitory moment, or the surprise factor, intrinsic component of the perspectivist character of all literature centered, like this one, in offering the new image, the custom, in a new light.

This type of columns of a more narrative than argumentative nature, heirs of the article of customs, are also characterized by their heterophony (multiplicity of voices) and even heteroglossia (presence of different levels of language), because the columnist not only uses his own voice, but this is composed of the voices of others, the voices of society (García Álvarez, 2007). And not only does that plurality of voices exist in the narrator itself, but also the columnist draws directly or subtly an imagined interlocutor, some other with whom to establish his dialogue and complete the ultimate goal of communication.

The column, which is born from the author’s unique perspective, aims to see the light in a social and already polyphonic support. The columnist, when constructing his speech, constructs his sentence and it is composed of a polyphony of voices, even if they are presented under the baton of the narrator self.

1.5. The personal column of Alfonso Sánchez in the newspaper Informaciones

The beginnings of the work of Alfonso Sánchez in the newspaper Informaciones in the 50s coincide with the popularization of the term column to designate the signed article that is published regularly and occupies a predetermined space in the newspaper (Casals, 2000), a type of opinion article in which both the expression and its content matters, the form, as the background, and, therefore, its literary quality.

The most immediate classification that can be made of the column as a kind of opinion is that which divides it into two large groups: the analytical columns and the personal columns. We will discuss here the personal column, the object of our analysis, whose scholars place it halfway between literature and journalism: it allows the author to explain himself with the greatest freedom, since his prestige places him above the daily demands of the journalistic collective, without being subject to greater disciplines, and his signature is sufficient endorsement so that the readers look for him by himself, since they trust in the value or the grace of some writings whose pact of reading is based largely on the confidence.

The personal column is an artistic synthesis between rationality and subjectivity, as if it were the most gratifying syncretism of all that has constituted our intellectual history since the eighteenth century. César González Ruano recognized that his personal experience taught him that it is precisely the intimacy, confidence, confession of what individually occurs, which is more attractive and popular. This type of columns, riding between journalism and literature, is a narrative in which, as in no other, the reader has more the feeling of being listening the journalist’s personal opinion and participating in his internal dialogue and debate, instead of facing the solitary reading of a literary text.

In addition to its narrative and descriptive nature of uses, traditions, celebrations and characteristic characters of its time, Alfonso Sánchez’s columns are a reflection of the rhetoric of the traditional article also because of its dialogic and polyphonic character. Many examples of polyphony are in their columns when he picks up those other voices in society plaguing his texts consciously or unconsciously of heterophony to through dialogue.

Alfonso Sánchez’s trajectory is closely linked to the Madrid press, in whose heads he collaborated without interruption between the 1950s and 1981. During the Franco regime he always avoided any exaltation or criticism, opting for the social and cultural agenda in the first period, and later by the observation of customs.

Sanchez dedicated hundreds of columns to the society of Madrid, especially the high society, well-known people of the capital, those names that stood out in bold or capital letters for readers to focus their eyes.

Alfonso Sánchez begins his work as a film critic in El Alcázar, as well as collaborating in the magazines Primer Plano, Cámara, Revista Internacional de Cine or Tele-Radio. From the first issues he collaborated with La Codorniz in the section ‘Are you sure?’ In 1951 he began writing on the Monday Sheet and later, in 1954, in the evening newspaper Informaciones until 1980. His first column in the newspaper Informaciones “By the sun and see the ‘Duke’” he wrote on November 1, 1954. The last, “See you soon, with cinema”, came out on February 2, 1980, coinciding with the closure of the newspaper.

The Informaciones newspaper was a conservative newspaper, pioneer of the Madrid evening press, founded in 1922 by the Aragonese journalist and politician Leopoldo Romeo. After the end of the contest, the newspaper was directed by the journalist Víctor de la Serna, with an accentuated Germanophile editorial line. In 1956 it was acquired by the company Bilbao Editorial and in 1967 it came to depend on the Spanish Democratic Union. A year later, the newspaper became the property of a group of bankers headed by Emilio Botín and that was his stage of modernization and expansion. In that renewed Informaciones, Víctor de la Serna Gutiérrez-Répide is appointed CEO, his brother Jesús de la Serna, director and the young journalist Juan Luis Cebrián, editor in chief and then deputy director. During that period an expansion of the newspaper is produced until reaching 74,000 copies per day in 1976 and, for its pages, encouraged by the brothers de la Serna and Cebrián, the best journalistic staff of the moment passes.

Sánchez was also a professor at the Complutense and correspondent and jury at the most important European film festivals from the 50s until his death. Throughout his career he worked as a collaborator in Spanish Television, in film programs such as En Antena, Panorama de Actualidad, Punto de Vista, Buenas Tardes or Revista de cine. He died on September 8, 1981.

2. OBJECTIVES

The objective of this article is to define, describe and analyze the use of the referred discourse as a rhetorical resource in the opinion article, very frequent in Alfonso Sánchez’s columns: the plausible as a substitute for reality so it is convincing for the reader, starting from the hypothesis that Sánchez’s columns are inheritors of Larra’s traditional article because of his dialogic and polyphonic character, as well as the description of uses and characters of his time.

3. METHODOLOGY

For the analysis of the persuasive, aesthetic and cognitive effects of the dialogic components of the journalistic work of Alfonso Sánchez, ten columns published in the newspaper Informaciones from 1954 to 1980 have been selected under the title “My Column”. Columns of each of the three stages of his professional career have been chosen: beginning (50s) , consolidation (60s) and maturity (70s and 80s): “Acapulco en Ondarreta” of July 9, 1956; “The abstract as an overcoat garment” of November 24, 1960; “Yesterday I met Doña Fabiola as one more of Madrid” on December 1, 1960; “The tie” of October 23, 1975; “With perfume in the pocket” of January 17, 1976; “Bulls and rumors” of June 3, 1976; “The popular of L.A.E.” of February 2, 1977; “This starts hot, of course” of September 8, 1977; “Dogs are not allowed” of July 21, 1978 and “Calm opening” of October 7, 1978.

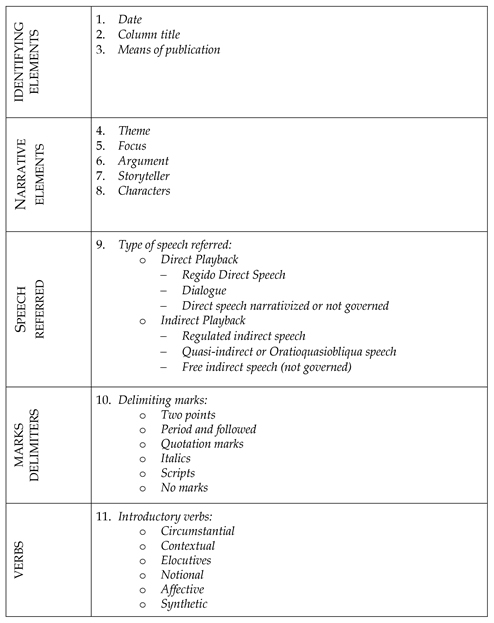

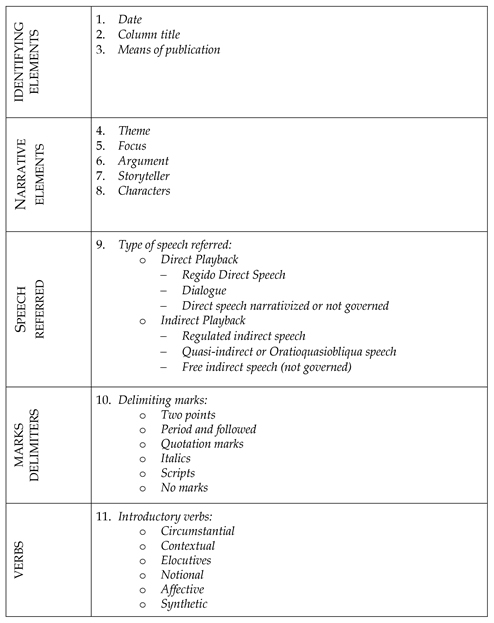

The analysis is carried out using a method of rhetorical and narratological analysis (Arroyas and Berná, 2015). The analysis has been carried out based on the rhetorical method that addresses the text as a significant unit, relevant for its syntactic and semantic aspects, with a pragmatic dimension. An analysis template was designed with the following categories:

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1. Template.

4. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

The predominant expressive modality in the analyzed columns is the demonstrative one, with abundant parts of referred discourse that are interspersed with narrative, descriptive and explanatory or evaluative fragments:

“It is possible that Acapulco beach is the beauty they say. Ondarreta was more beautiful in the radiant morning, with the sun still unburning, with a clean and fresh water…” (“Acapulco en Ondarreta”, 07-19-1956).

“In front of the Town Hall, two rows of municipal guards in grand gala. Many people. Personalities were arriving…” (“Yesterday I met Doña Fabiola as one more Madrilenian”, 1-12-1960).

The entire narrative is constructed from what the narrator-character tells, in the first person, of what he has heard from others during the celebration of a cocktail, an exhibition, a royal visit, the shooting of a film, an awards ceremony, etc.

In the use of the referred discourse, direct reproduction stands out, mainly the direct discourse referred to, although it also uses in the majority of the analyzed columns, the dialogue:

CONCHITA MONTES arrived wearing around her neck a handkerchief that Mathieu has given her. Her painting is very decorative in these garments. I asked:

- Hey, Conchita, does the abstract wraps up warm?

The COUNT OF YEBES, who was in the dialogue, told something good:

- A friend of mine heard that Mathieu is the son of a multimillonaire and asked: “When did your father throw you out of the house?” (“The abstract as a piece of warm clothing”, 11-24-1960).

Mayte always honors with her sympathy, although she has us neglecting the cinema. I ask her:

- When will be a Mayte Film Award?

He makes a gesture of doubt. Maybe cinema should place her in her films. She is beautiful, intelligent,

with temperament She destroys:

- Go, stop joking. (“The populars of LAE”, 02-02-1977).

I wink at Rafael Azcona in request of his complicity and I ask a new question:

- And transvestites, do you admit them?

The patron or the maitre stares at me with a face of not understanding anything. With some shyness they respond:

- Well, man, if they come... (“Dogs are not allowed”, 07-21-1978).

Two clearly differentiated discourses coexist (narrator-protagonist and character-interlocutor), in which the narrator’s speech syntactically governs the character’s discourse through formal ways (colon and hypen) and verbs dicendi or sentiendi, with some cases of deictics and adverbial phrases that point to the character’s time (in the morning, later, next year, then, there will be time, in other places, for a long time, take time, for once, this year, this pause, calmly, someone last night, now I see him here, he leaves soon, among others).

Together with the literalness of the quotation, the immediacy and closeness that this type of discourse provides, in addition to the agile rhythm that it gives to the narration, the determining position of the narrator, who controls other people’s discourse as a reproducer, stands out in its columns. A position reinforced by the use of the first person and the peculiarity that all the interventions of other characters are always interpellations to the narrator himself, which makes him the protagonist. Everything that is told is perceived by the narrator as a witness, but also as a primary interlocutor, as a character. Examples of this type abound, like the one in the column “This starts hot, of course” (8-09-1977):

“I had not seen her for a long time. On Saturday I found her at the hairdresser…”

The main effect of the referred discourse is narrative. It is about very brief, fragmentary interventions that with short introductions of the characters, streamline the pace of the narrative, visualize the scenes and, above all, reinforces the polyphony favoring refraction between speeches of different characters. The selected phrases of the characters serve to support the ideas of the narrator, on some occasion with the anonymity of the author of the quote. An example is found in the column “This starts hot, of course” (8-09-1977):

“When discussing the events with the pharmacist, he commented: -The serious thing will be if it affects the metallurgy. Because metallurgy, Monsieur, is very important...”

Some interventions by way of dialogue without replication play a purely anecdotal, humorous and scenario creation function, although the character characterization resource is also important as in the column scene (“Calm opening”, 7-10-1978) in which the narrator addreses informally the waiter of the tasca:

- “Hey, Manolo…”.

The narrator’s intervention is also appreciated through value judgments and expressive resources through the type of verb chosen and references to the mood or space-time situation of the characters. With these expressive resources, the narrator conditions the image of the characters and gives the story a tone that oscillates between irony, humor and subtle criticism. The introductory verb plays an initial role with respect to the participants of the communicative situation in pragmatic terms.

The narrator gives the context with the verb, which is fundamentally contextual (said, comments, asked, spoke, told, answered), elocutive (he whispers, I thought, he begged, he sentenced, he qualified, he proposed, he repeated ) and notional ( he whispers confidentially, he complained, ask suddenly, he reassured, he comforted, he is indignant, cheer up , etc.).

Alongside the verb, the pronouns ‘me’, ‘nos’, ‘le’ ‘lo’, ‘la’, ‘las’ , among others, are characteristic in Sánchez’s columns , which supports the personal character of the narration and the prominence of the narrator, with the consequent effect of closeness, immediacy and subjectivity, without losing truthfulness and realism. These examples are found in: he trusted me, he reproached us, I asked him, he comforted her, he corrected him, I proposed him, they gave me, among others.

The dialogue opens the narrative to a plurality of approaches through the verbal exchange of the characters by limiting the voice of the narrator, who does not impose his point of view. It is also a way to favor criticism or description of customs from the plurality of testimonies, capturing the complexity of social reality. In this way, the main idea of the article is put into the mouth of another, as a sentence, which the narrator will then repeat. This example is found in the column (“Calm opening”, 7-10-1970):

“López Sancho told me when he left:

- People have no idea of fussing or repeating tragedies again”.

The dialogue highlights the immediacy of events and increases the dynamism of the events narrated, which brings credibility to conform to the rules of human behavior. The use of narratives allows Alfonso Sánchez to give access to his articles to voices other than his own, so that this polyphony reinforces the rhetorical nature of the text, helps him direct his ideas, defend them, justify them and reinforce them if necessary. So much so that the dialogue merges with the rhetoric so that the column, under the direction of a seemingly dominant voice, is full of voices that resonate with each word.

5. CONCLUSION

A first-person narrative by a witness narrator who tells what he sees and hears in different encounters with other characters is the most characteristic modality of Alfonso Sánchez’s columns, in which dialogue plays a fundamental role as a persuasive resource. After the analysis, it can be concluded that Sanchez’s personal column falls within those texts that do not claim the reflection of reality, but, feeding on it, they reinterpret it through a polyphony of voices, directed under the baton of the ego narrator, who acts at all times as a first person witness.

Alfonso Sánchez’s columns rescue the dialogic and polyphonic character of the rhetoric of the local customs article. The narrator’s speech is tinged with the speeches of other characters representing the social and cultural spheres he frequents. Through dialogue, the narrative is dramatized, becoming more complex by the multiplication in the story of figures, stories, time and space. The use of the narrative perspectivism and expressive and descriptive multifocality as technique used in the preparation of articles extends the psychological and characterological complexity of the story and brings it closer to the reader. Although this resource tends to the fictionalization, to the extent that a figure becomes a narrator of his own story in first person it gives also an effect of verisimilitude.

The dialogue also has the effect of highlighting the immediacy of events. By opening the voices of the characters, the referred discourse increases the dynamism of the events narrated. In this way, it brings credibility by adjusting to the rules of human behavior.

Dialogical perspectivism contributes to open the narrative to a plurality of approaches through the verbal exchange of the characters as a way of limiting the presence of the narrator, who goes to the background to create the effect that he is not above his readers and the illusion of not imposing his points of view as a narrator, a type of discourse that fits the ironic tone so characteristic of Alfonso Sánchez’s style.

REFERENCES

1. Amado A (2014). Los hechos y los dichos en las noticias: la polifonía del discurso periodístico. Romanica Olomucensia 26(2):143–156. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5053281

2. Arroyas E (2009). La objetividad y la función democrática del periodismo. Murcia: Ucam.

Recuperado de https://www.academia.edu/2035998/La_objetividad_y_la_funci%C3%B3n_democr%C3%A1tica_del_periodismo

3. Cantero V (2011). El perspectivismo como técnica narrativa en los artículos de costumbres de Larra. La Laguna. Revista de Filología, 29, 21-36. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3662466

4. Aristóteles (2005). Retórica. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

5. Armañanzas E, Díaz J (1996). Géneros de opinión. Bilbao: Eunsa. Arroyas-Langa E, Berná-Sicilia C. (2015). La persuasión periodística. Barcelona: UOC.

6. Bajtin M (1989). Teoría y estética de la novela. Madrid: Taurus.

7. Burguet F (2008). Las trampas de los periodistas. Barcelona: Trípodos.

8. Casals-Carro MJ (2000). La columna personal: de esos embusteros días del ego inmarchitable. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 6, 31-51.

9. Chillón A (2014). La palabra facticia. Literatura, periodismo y comunicación. Barcelona: Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.

10. Compagnon A (2015). El demonio de la teoría. Literatura y sentido común. Barcelona: Acantilado.

11. Fernández-Lagunilla M, Pendones C (1993). Recursos polifónicos del narrador en el discurso periodístico. Revista de Filología Románica, 10, 285-294. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38841629.pdf

12. Forneas-Fernández MC (2005). El artículo de costumbres: crónica, crítica, literatura y periodismo. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 5, 293-308.

13. García-Álvarez MF (2007).Las columnas de autor: Retórica y… ¿Diálogo? Caso práctico: La presencia del “otro” en el columnismo de Rosa Montero. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 13, 399-417.

14. Genette G (1989). Figuras III. Barcelona: Lumen.

15. Jakobson R (1984). Ensayos de lingüística general. Barcelona: Ariel.

16. Jameson F (1980). La cárcel del lenguaje: perspectiva crítica del estructuralismo y del formalismo ruso. Barcelona: Ariel.

17. León-Gross T (2008). El artículo literario: Manuel Alcántara. Málaga, España: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga con la colaboración de la Fundación Manuel Alcántara.

18. López-Pan F (1995). La columna como género periodístico. Pamplona: Eunsa. Martín-Vivaldi G (1993). Géneros periodísticos. Madrid: Paraninfo.

19. Molero-De-La-Iglesia A (2004). Didáctica del texto narrativo. Estudio y análisis del discurso. Madrid: UNED.

20. Moreno-Espinosa P (2002). Géneros para la persuasión en prensa: los artículos de opinión del diario El País. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 5(46). Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81954612

21. Peñas-Ruiz A (2014). El artículo de costumbres en España (1830-1850). Vigo. Academia del Hispanismo.

22. Perelman CH, Olbrechts-Tyteca L (1989). Tratado de la argumentación. La nueva retórica. Madrid: Gredos.

23. Reyes G (1984). Polifonía Textual. La citación en el relato literario. Madrid: Gredos.

24. Santamaría-Suárez L, Casals-Carro MJ (2000): La opinión periodística. Argumentos y géneros para la persuasión. España: Fragua.

25. Spang K (2009). El arte de la literatura. Otra teoría de la literatura. Pamplona: Eunsa.

AUTHORS

María Ángeles Villa García: Degree in Journalism (June 2001), at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the Catholic University San Antonio de Murcia. She is currently doing a PhD at the Catholic University of Murcia, in the Social Sciences Program. Contract of work in National Radio of Spain in the territorial station of Murcia. Tasks performed: writing and presentation of newsletters, equipment management and self-control; at the Europa Press News Agency, Murcia. Tasks performed: news writing; in the newspaper La Razón. Tasks performed: news writing; and in the Murcia Autonomous Television, 7RM. Tasks performed: News editor.

mangelesvilla@hotmail.com

Enrique Arroyas Langa: With an active research six-year period recognized by the CNEAI (2006-2014), Enrique Arroyas Langa (Valencia, 1966) has a degree in Information Sciences from the University of Navarra and a PhD in Communication from the Catholic University San Antonio de Murcia. Since 2003 he is a professor at the Faculty of Communication of the UCAM, where in addition to teaching the subject of Journalistic Writing, he is the director of the Title of Expert in Political Communication.

earroyas@ucam.edu

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6578-1571

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=9cZPGhAAAAAJ&hl=es

Índice H: 4