10.15178/va.2018.143.135-160

RESEARCH

THE ACADEMY AGAINST THE POST-CONFLICT AND PEACE. CASE STUDY

LA ACADEMIA FRENTE AL POSCONFLICTO Y LA PAZ. ESTUDIO DE CASO

A ACADEMIA DIANTE AO POS CONFLITO E A PAZ. ESTUDO DO CASO

Clara-Janneth Santos1 Doctora en Ciencias de la Información: U. Complutense de Madrid (España) y Comunicadora Social-Periodista: U. Autónoma de Bucaramanga. Docente investigador U. Autónoma del Caribe, Colombia

Jennyfer Solano1

Sergio Nieves1

1Autonomous University of the Caribbean. Colombia

ABSTRACT

Since 2014, the Autonomous University of the Caribbean, UAC, supports the national policy of dialogue and peace building in Colombia from the Caribbean region: a process that only recently has shown its first political and international consequences. To this end, the UAC structured and implemented the ‘Chair of Peace’ in Undergraduate Studies; created the –kwon as- Institute for Higher Studies for Peace; established series of national and international alliances, generating activities and events in which the university community participates; involving it into the process as part of the coordinated effort to achieve its social acceptance. This descriptive study develops a first phase of diagnosis throwing information obtained through a survey of a sample of 281 students of the subject Society and Culture for Peace looking to know: a) Knowledge and Pre-knowledge students have on History of Colombia and the Armed Conflict; b) the mechanisms and channels that these young people use to obtain the information; and c) the student’s (s) perception of the Peace Agreement and the Colombian Conflict.

KEY WORDS: Culture of peace; high education; ict; university; postconflict

RESUMEN

Desde 2014 la Universidad Autónoma del Caribe –UAC- apoya en la región Caribe, la política nacional de diálogo y construcción de paz en Colombia. Para ello estructuró e implementó la ‘Cátedra de la Paz’ en Pregrado; creó el Instituto de Altos Estudios para la Paz; estableció alianzas nacionales e internacionales, generando actividades y eventos en los que participa la comunidad universitaria. Este estudio que se presenta, de carácter descriptivo, desarrolla una primera fase de diagnóstico arrojando información obtenida mediante una encuesta realizada a una muestra de 281 estudiantes de la asignatura Sociedad y Cultura para la Paz durante el 2016. Se pretende determinar: a) Pre-saberes y conocimientos que tienen los estudiantes sobre Historia de Colombia y del Conflicto Armado; b) los mecanismos y canales que utilizan estos jóvenes para obtener la información; y c) la percepción del estudiante en cuanto al Acuerdo de Paz y el Conflicto colombiano.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Cátedra de la paz; cultura de paz; educación superior;TIC; universidad – posconflicto

RESUME

Desde 2014 a Universidade Autônoma do Caribe – UAC – apoia na região Caribe, a política nacional de diálogo e construção da paz na Colômbia: um processo que só recentemente mostrou suas últimas consequências políticas e internacionais. Para isso estruturou e implementou a ¨Cátedra de la Paz¨em Pregado, criou o conhecido como instituto de Altos Estudos para a Paz, estabeleceu uma serie de alianças nacionais e internacionais, gerando atividades e eventos nos que participam a comunidade universitária, implicando-a no processo como parte do esforço coordenado para conseguir sua aceitação social. Este estudo que se apresenta, de caráter descritivo, desenvolve uma primeira fase de diagnostico mostrando uma informação obtida mediante uma encosta realizada em um total de 281 estudantes da matéria Sociedade e Cultura para a Paz durante o ano de 2016. Pretende-se determinar uma série de variáveis: a) Pré saberes e conhecimentos que tem os estudantes sobre a matéria de História da Colômbia e do próprio Conflito Armado;b) os mecanismos e canais que utilizam estes jovens para obter a informação, e; c) a percepção concreta do estudante (e do corpo estudantil) enquanto a todo o referente ao Acordo de Paz e o Conflito Colombiano.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Cátedra de la Paz; Cultura de Paz; Educação superior; TIC; Universidade pós conflito

Received: 28/11/2017

Acepted: 17/01/2018

Correspondence: Clara Janneth Santos

Janneth.santos@uac.edu.co

Jennyfer Solano

Jennsolano96jsb@gmail.com

Sergio Nieves

Sergio.nieves@uac.edu.co

This text presents results of the project Design and Implementation of an Educommunicative Model for the Promotion of the Culture of Peace in the Caribbean Region attending to the University Social Responsibility. Registered: PRYINT-081-2017 -University Autónoma del Caribe (Colombia).

Cómo citar el artículo

Santos , C. J. Solano, J. Nieves, S. (2018). La academia frente al posconflicto y la paz. Estudio de caso. [The academy against the post-conflict and peace. Case study].

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 143, 135-160

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.143.135-160

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1109

1. INTRODUCTION

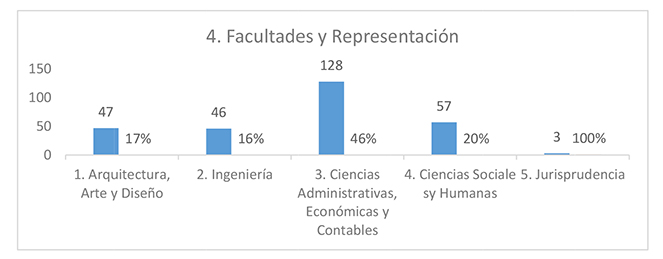

The results of the survey applied to 281 young people from a population composed of 1,025 students enrolled in 2016/01 in the subject Society and Culture for Peace (SH0055) that teaches to all the Programs of the Autonomous University of the Caribbean, Department of Humanities (attached to the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences), within the training block called Basic Institutional Area, ABI. The population groups (read ‘N’) on which the sample of 281 students enrolled in the so-called ‘Chair of Peace’ were selected were extracted from those enrolled in the twenty-five (25) Programs attached to five (5) Faculties of the UAC, namely: Faculty of Administrative, Economic and Accounting Sciences (N: 467 students), Faculty of Social and Human Sciences (N: 207); of Architecture, Art and Design (N: 173); of Engineering (N: 168) and Jurisprudence (N: 10).

The subject is structured around (3) units with training purposes that respond to (3) large topics that teachers synthesize as follows: History of the Conflict; ICT and Postconflict; and Corporate Social Responsibility in the face of the Post-Conflict. Talks were held with the teachers of the subject and consequently the following working hypotheses were determined: 1. Young people of the 21st century are unaware of the history of Colombia, but they are informed about the current negotiation process in Havana; 2. The students of the UAC inform themselves about the Agreements through social networks; 3. The young people of the UAC perceive peace as a possible process but they do not recognize commitments to the Post-Conflict. It was determined to survey taking into account thematic Syllabus on History to see level of knowledge as: a) the History of Colombia; b) the Political Agreements with armed groups and the political inclusion of the ‘insurgents’; and c) the -current- Agreement and Negotiation with the FARC in 2016 (see annex: Survey). It was asked about the mechanisms for acquiring information according to different scenarios and themes related to the Post-Conflict and finally inquired about its perception with respect to the current Peace Process.

1.1. The political, media and institutional climate of the UAC in 2016

When applying the survey, the historical context of the moment (February 2016) was taken into account, determined by the eventual signing of the Peace Agreement of the government of Juan Manuel Santos with Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, alias ‘Timochenko’, Commander in Chief of the Forces Armed of the Republic of Colombia-Popular Army, FARC-EP, scheduled for March 23, 2016-fact that, finally, was postponed until September 26 of the same year.

With regard to the academic context of the Autonomous University of the Caribbean (UAC), it was taken into account that 2014, 2015 and 2016 were years in which the institutional action evidenced its peace policy through academic events and courses that promoted the social dialogue and a climate of discussion around the post-conflict, peace and agreements. Thus, in 2014, the VI Communication Week was organized under the title: “Public Opinion, New Narratives and Post-Conflict”. The Center for Higher Studies for Peace, created in December 2014 (called the Institute in 2017), organized Forums, Workshops, Conferences, taught Diplomats and directed multiple actions to promote social dialogue and inter-institutional interaction to support the victims of the conflict.. A group of students was prepared and sent to participate in the World Summit of Nobel Prizes (Barcelona, 2015 and Bogotá, 2017); Seminars and Seminars were organized and imparted by the Office of the Vice-Rector for Extension, around the Post-Conflict and the Culture of Peace (1). Intervention and training was also carried out on communities affected by the Post-Conflict (the Atlantic Forte Program served 815 families in the region); from the Digital Platform of Entrepreneurship “ConAcción” provided employment to women victims), etc. Media actions are highlighted in collaboration with allies of the UAC as in the case of the Campaign ‘Respira Paz’ of the UNDP Office and the participation of the Students of the UAC in the calls of the “Manos a la Paz” Program in 2015 and 2016, among others. It should be noted that the construction of peace is part of the Institutional Educational Project, PEI, and the peace policy of the UAC.

(1) To expand the information on the actions carried out by the UAC regarding peace, it is suggested to consult the article by Santos, CJ (2016), heading entitled: “From theory to practice. The Uniautonomous Peace Culture “(pp. 621-625). In addition, there is profuse information on the website of the Institute for Higher Studies for Peace; the Digital Institutional Repository (DSPACE), and in the books of Vargas, R .; Santana, J. (2015) and the book by Vargas, R. entitled: “Personajes” (2017).

This changing and promising framework of peace invites us to deepen into what the students of the UAC think in order to better understand how to face the challenges generated by the Post-Conflict and the tools that the academy requires to educate in the 21st century, as well as, the methodologies to be considered in the context of the interaction of ‘digital native’ students with ‘digital migrant’ teachers (Prensky, 2001).

Why and why characterize these students? The answer arises from the incessant changes experienced by education and today’s society. Changes in what is observed with Martin Barbero, that “... education is no longer thinkable from a model of school communication that is exceeded both spatially and temporally by training processes corresponding to an informational era in which the” age of learning it is all “, and “the place to study can be anyone (VV.AA, 2012, page 106). On the other hand, and regardless of terminological disquisitions, we must bear in mind that the population under study are the young people called ‘millennial’, ‘millennium’ or ‘generation Y’; that in Colombia, besides characterizing them as ‘digital natives’, born with the rise of Information and Communication Technologies, ICT, they have also acquired the age of majority with the new Constitution (1991), which outlined multiculturalism, inclusion and peace as bastions of the identity of Colombians. To this we add the changes of the educational and communicational paradigm that stipulate the obsolescence of the educational instructional model; the necessary inclusion of a new educational model that gives importance to the development of critical thinking, citizen participation, the empowerment of the media, the defense of human values, the importance of democratic values and the environment, among other terms that shape a new panorama, a new humanism and a new identity (UNESCO, 2005, Pérez Tornero and Varis, 2010).

But if the teachers of the UAC (digital migrants), point out that they form university students to move in intercultural and global contexts, they should also be prepared to talk about the local and act on their environment. However, teachers say that these young people have little knowledge of their own history - which can be attributed, in part, to the suppression since 1994 of the subject of ‘History’ in schools, to make it part of the subject of Social Sciences. A fact that historians ratify by pointing out that this “has led to ‘historical or cultural’ amnesia ‘or’ illiteracy ‘that leads to the loss of personal referents and points of orientation for Colombian society” (Morales, 2016, page 31) -.

Young people have lost their identity from a historical framework and also the connection with previous generations - the legacy of the elderly; Those who have lived since the early twentieth century, such as the War of a Thousand Days (1899-1902), through partisan violence (1948-1958), the increase of rural and urban conflicts with the guerrillas that emerged in the decades 1950 to 1960; and they have lived the drug war in the 80s, among the great conflicts of the country. Identity that, in addition, young university students experience from connectivity and globalization, which invites “offshoring” and “de-temporalization”, among others (VV.AA., 2012). Therefore, there is a need to know and perhaps confirm the levels of knowledge of these ‘millennials’ to see how to reaffirm their national identity; see to what extent the agents of mediation for learning have changed (the classroom, the teacher and the book no longer configure the axes of learning). And see the place that ICTs have occupied to build symbolisms and meanings with the audiovisual language and other languages excluded from the school setting -as Martín Barbero points out- (VV.AA., 2012).

This research seeks to characterize the students of the UAC within the framework of learning as a research process, understanding with Delors that we live “in an educational society in which everything can be an opportunity to learn and develop the capacities of the individual” (1997; p 35) and assuming with Juan Freire that “The experiences offered by public spaces, communities of interest, leisure, Internet... and the almost unlimited possibilities of communication open a universe of educational possibilities that should be recognized as such and considered in curricular designs and educational programs. “(VV.AA., 2012; p.70)

Therefore, we approach the learning experience of young Colombians, seen from the microcosm represented by the students of the subject Society and Culture for Peace of the Autonomous University of the Caribbean, investigating -from the problematic of armed conflict-, What do they know? What they do not know? How have they got information? What are they interested in? or not; How do they perceive the current reality of the Peace Accords and what do they believe? This is a form of approach to avoid, as Martín Barbero points out, the deepening of the existing gap between the educational system and the experience of young people, which is given by

“...a model of school communication that has nothing to do with the communicative dynamics of society, that is, because of a school that continues to demand that its students leave their body and soul, their sensibilities, their experiences and their cultures, be they sonorous, visual, musical, narrative or scriptural “(Martin-Barbero, 2009, page 23).

The results of this survey place us in this reality and seek to move from theory to practice in the framework of this research project.

2. OBJECTIVE

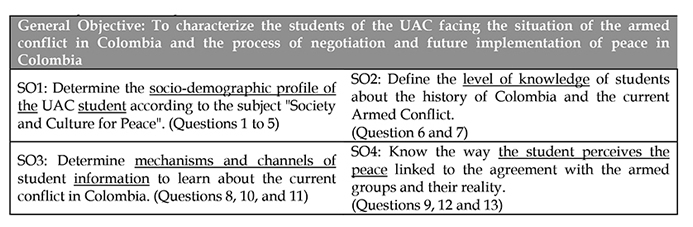

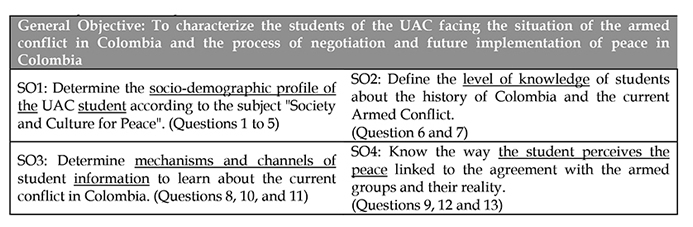

The research is based on the following Objectives matrix. Information was collected through a questionnaire prepared with qualitative polytomous variables:

Table 1. Matrix of Research Objectives

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Statistical justification of the investigation

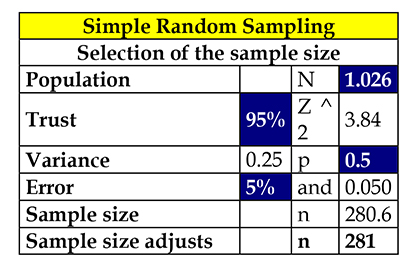

The total population enrolled in the subject SH0055 is 1,025 students. Surveys were conducted in 9 groups, between February 15 and 22, 2016, as follows: 1 group per day, except Friday and Monday, which surveyed 2 groups: day and night. Of the 512 students enrolled in the 9 groups, 344 were surveyed who attended the class, that is, 67.18% of those enrolled in the subject Society and Culture for Peace. The level of absenteeism was 32.82%, so the group was reduced proportionally by extracting incorrect data, canceled surveys, and / or incomplete surveys, to finally work with 281 records. The selection of the sample was based on the following formula:

Which is used for finite populations, from a random sampling, with the elements that are detailed below.

Table 2. Determinación de la muestra. La muestra es: 281 estudiantes.

These elements guaranteed an optimal sample size representative of the student population, which proceeds to characterize all individuals who are part of this study. The proportion of the sample was also made by Faculties.

Graph 1. Enrolled in 2016 and representation according to Faculties

The sample was obtained by stratified sampling since the courses did not have the same number of students and a proportional allocation was made to each element of the population, so that from a sample size for finite populations it was calculated in 281 students, which were selected by Faculties.

3.2. Observations

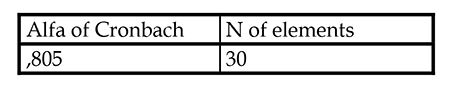

The validation of the instrument was made with the professors of the Chair of Peace and the Coordinator of the Department of Humanities, as a filter to determine the viability of the questions and thus have external peer evaluators that would allow greater transparency and assertiveness in the questions. The reliability test of the instrument was carried out, using the Cronbach’s Alpha, which yielded a value of 0.80 after analyzing the items of the instrument, this value being good for basic investigations.

Table 3. Reliability statistics.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Objective 1: To define the sociodemographic profile of students. Questions 1 to 5

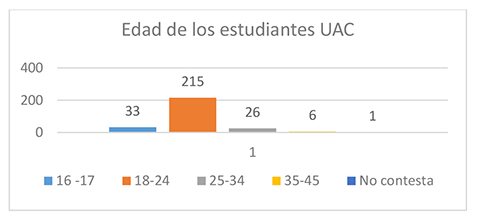

Graph 2. Age of the respondents of the subject Society and Culture for Peace

The socio-demographic profile of students of the subject Society and Culture for Peace in the first half of 2016 is composed of a population with a slight majority of males (54.09% of respondents) compared to 45.9% of women from the Caribbean region (94.28%), mostly from the Department of the Atlantic (72.14%) and from Barranquilla (61% of the total sample). The sample taken in February 2016 reveals that 88.57% of the students have ages ranging between 16 and 24 years old, that is, they are young people born in the dawn of the new Constitution of 1991; that are within the age of majority in which responsibilities and civic obligations are acquired.

As for the schools, a classification was carried out, in line with the Law 115/1994, art. 4, considering the type of educational service provision: official or public establishments and private establishments. The provision of educational services in private schools can be: lay (foundations, associations, cooperatives, etc.) or confessional (Catholic, Presbyterian, Evangelical, etc.). The data collected show that 34.52% of the population has completed baccalaureate studies in public establishments; 33.8% comes from private (lay) schools; and also 27.4% come from confessional or religious establishments, therefore, the majority comes from the private sector (lay people + confessionals). The population of Barranquilla represents 61% of the sample with 173 respondents, so at the Undergraduate level, the UAC is a University ‘for all’, as can be seen: 1) Private Schools: 62 students; 2) Confessional Colleges: 51; 3) Public Schools: 52 students.

4.2. Objective 2: Determine the level of knowledge about the History of Colombia and the armed conflict. Questions 6 and 7

4.2.1. Level of Knowledge on Armed Conflict and History of Colombia

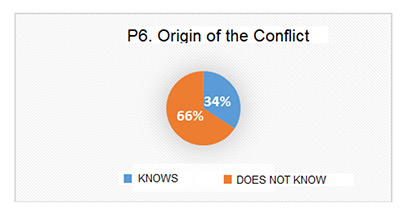

The data of questions 6 and 7 will be analyzed. Question 6 was formulated as a multiple selection, providing several options with significant dates.

Graph 3. The students locate, chronologically, the Origin of the Armed Conflict in Colombia

Although the media discussed this issue in 2015, it is observed that 66% of the students of the UAC (surveyed in February 2016), does not have exact knowledge about the origin of the armed conflict; versus 34% that does determine a date.

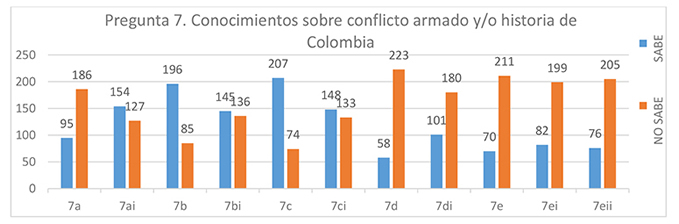

4.2.2. Question 7: Level of Knowledge about the Armed Conflict and / or the History of Colombia

Question 7 encompasses a series of eleven correlated questions that seek to know the level of knowledge about historical events in the country (2).

(2) There are 11 factors that the student correlates, including the date of the Political Constitution of Colombia; Political participation of armed groups of right and left and actors within the current Negotiation Process.

Graph 4. Level of knowledge about the armed conflict and the history of Colombia

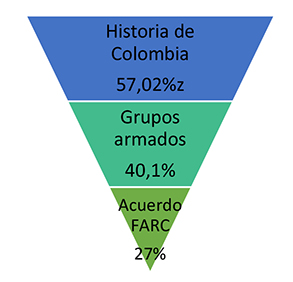

To ask these questions, the teachers of the subject were consulted to verify the pertinence of the topics, which, at the time of the survey, had not been studied in class, but they should constitute pre-knowledge that form part of the Plan. of school studies of tenth and eleventh grade (3). The results vary, but, they show the following particularities: the first 6 items: level of knowledge about the history of Colombia (from 7a to 7ci), represent 55.38% of correct answers (arithmetic mean). In the case of question 7c, related to the Taking of the Palace of Justice, a greater level of success is observed (73% of respondents know). The items that measure level of knowledge about armed conflict and political groups are: 7bi; 7ci; 7d; 7di. The arithmetic mean shows that the level of knowledge is 40.1%. The items (7e to 7eii) measure the students’ level of knowledge about the current negotiation of the armed groups (FARC and ELN) with the Colombian government. Only 27% of respondents know about this topic. Which allows to represent the themes treated as an inverted pyramid of the level of knowledge of the students.

(3) Guide N ° 7 of Basic Standards of Competencies in Natural Sciences and Social Sciences, indicates, among the knowledge that a student handles in the tenth and eleventh levels about which the survey was asked, such as: “I explain the origin of the bipartisan regime in Colombia “; “I analyze the period known as ‘violence’ and establish relationships with current forms of violence.” “I identify the causes, characteristics and consequences of the National Front”, among others.

Graph 5. Levels of knowledge of the themes

Knowledge that constitutes weak points of learning, highlighting the ignorance about the Peace Agreement (current reality).

4.3. Objective 3: Determine mechanisms and channels of information that the student has to know the current conflict in Colombia. Questions 8, 10 and 11

The students of the UAC have obtained information through the scenarios: School (E1) and Media and Informational (E4) mainly. The analysis takes into account that a great majority of the students surveyed in 2016 had not received the Chair of Peace in their schools since the Decree that regulates the implementation of the same, 1038 of May 25, 2015, indicates the incorporation of the subject before December 31, 2015, so not all would have met that goal. In turn, the Decree, art. 3 ° determines the fundamental areas to which the chair of peace can be ascribed, namely: 1) Social Sciences, History, Geography, Political Constitution and Democracy; 2) Natural Sciences and Environmental Education and 3) Ethical Education and Human Values.

The information collected shows that the subjects mentioned by the students in the School Scenario (E1) are part of these areas, fact by which, in this research, it is said that cognitive knowledge comes from compulsory subjects without having a transversal or interdisciplinary approach. This is despite the fact that Decree 1038 suggests “taking advantage of cross-cutting areas to incorporate contents of the culture of peace and sustainable development” (Article 3, par.). Regarding the recurrence of responses in the E4 Media and Information Scenario, consideration is given not only to the motivation that the use of the Internet or ICTs may have for the new generations, but also to the fact that Armed Conflict (as a theme) has kept itself within the framework of illegality for decades, therefore, sources of information used to come from the media (especially news / events, issued by traditional media, although more recently also published on the Internet). Octavio Kulesz points out that “In the specific case of Colombia, the new technologies acquire an even more specific meaning: they appear directly associated with the construction of peace and the period of the” post-conflict “. (2017, page 9). The information provided by the youth of the UAC confirms this, in the manner of a microcosm that speaks of uses and practices of the ‘millennials’. It highlights the use of social networks, especially Facebook. In Colombia these networks have open platforms such as ‘Free Basics’ (formerly Internet.org) that provide free access. Setting up a way to use the service of young people, their practices and their experiences.

4.3.1. Question 8: Pre-knowledge about the culture of Peace from the school curriculum

The question seeks to identify pre-knowledge about the culture of peace curricularly acquired and from the Educational Institutions. The answers: ‘No’ / ‘None’ / ‘Empty’ account for the ignorance of this topic. In this regard, 42% (118 respondents) have not received information regarding the culture for peace in any subject of the school, a fact that is surprising, especially if it is mentioned that Law 115 of 1994 states that it is of mandatory compliance: “Education for justice, peace, democracy, solidarity, fraternity, cooperativism and in general, training in human values”(Article 14). On the other hand, it is observed that in the first semester of 2016, 58% (163 respondents) of the students who take the subject Society and Culture for Peace in the UAC state that they have acquired pre-knowledge (cognitive skills) around a culture of peace and, mainly, from subjects such as: History, Political Science, Social Sciences, Civics, Citizenship, Constitution and Democracy, Economy, Ethics and Values, Urbanity.

4.3.2. Question 10. Degree in which you have received information about the current Negotiation Process

In this case -as an example- options were offered, among which were: letters, brochures, media, polls, surveys, informative events, workshops, seminars, courses. The results show that 165 students (58.72%) claim to have received information about the current Negotiation Process in Havana (they have been informed through ICT or with: surveys, informative events and university talks). The remaining 116 respondents (41.28% of the surveyed population) affirm that they have not received information -to date- about the Negotiation Process.

4.3.3. Question 11. Form of acquisition of information on Armed Conflict

In this battery of questions, it is interesting to know how informed the UAC students are about the following (10) subtopics: Armed Conflicts in the world; The Colombian conflict; Emergence of guerrillas in Colombia; Negotiation in Havana; War and environment; Ethics and conflict; Constitution and conflict; Technologies and conflict; Culture, Sport and conflict; and Participation and conflict. The analysis invites us to review the acquisition (appropriation) of information / knowledge from a multiple perspective that Delors called “... an educational society in which everything can be an opportunity to learn and develop the capacities of the individual” (Delors, 1997, p. 35). From this perspective, the following Possible Scenarios (E) were defined to acquire the information related to the armed conflict(s).

a. E1: School Scenario: compulsory school subjects and academic complements such as seminars, workshops, etc. (including information that comes from the curricular and the extracurricular);

b. E2: Extracurricular Scenario: information obtained in: neighborhood, library, church, museums, etc.

c. E3: Family and / or Personal Scenario: source of information provided by grandfather, father (s), brother (s), etc., / source provided by friends, teachers, etc.

d. E4: Media and Information Scenario: Mass Media and Internet-derived media categorized as follows: 1. MMC; 2. Social Networks; 3. Content Platforms; 4. Search engines and databases.

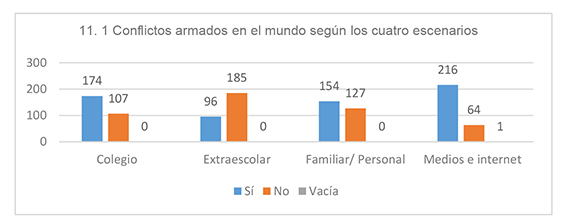

4.3.3.1. Armed conflicts in the world

The aim is to know how the students surveyed are informed about the themes of ‘Armed Conflict in the World’ and it is observed that, despite the globalized scenario presented by the 21st century, educational establishments offer little information of a universal nature. The results show preferences in the way information is obtained in relation to armed conflicts of a universal nature.

Graph 6. Armed conflicts in the world according to Scenarios

Students are informed mostly through the New Information Technologies, E4: Media and Information Scenario (Mass Media and Internet), followed by E1: School scenario (subjects, seminars, workshops, etc) and E3: scenario family / personal; finally, it seems less feasible for the world theme to be addressed in the extracurricular stage E2 (neighborhood, libraries, church, museums, etc.). Let’s see how this is represented according to the importance that students give to each Scenario (E):

Armed Conflicts the world: E4 > E1 > E3 > E2

Regarding the school (E1: School scenario): While students are informed from the compulsory subjects, it is evident that the schools do not strive to provide other perspectives of the subject that allow to introduce global visions, nor take the student out from the scope of the classroom . The respondents have not received information from workshops, seminars, talks, or others from the school. On the other hand, 107 respondents say ‘no’ have received information about the armed conflict in the world since (E1) , which leads to reflect from the curriculum: how to project citizens to act in a globalized world?

With regard to the Extracurricular Scenario (E2), it was observed that more than half, specifically 185 respondents, ‘Not informed’ about conflicts in the world by any extracurricular means. On the other hand, in 91 cases it is observed that the libraries (34), the neighborhood (27), the churches (10) and the museums (9), constitute spaces that provide information to young people. Finally, 5 of these young people say they receive information through brochures, books, from the Internet or at home.

The Family / Personal Scenario (E3) is subdivided as follows: Family scenario: parents, grandparents, uncles, siblings, cousins: 100 records, (35.6%). Personal scenario: friends, teachers, colleagues. 34 records (12% of respondents). Mix of two environments: 2 registers. Answers “No” / Do not answer: 127 records that represent 45.2% of respondents. It is confirmed that students do not go to the Family / Personal Scenario to learn about armed conflicts in the world.

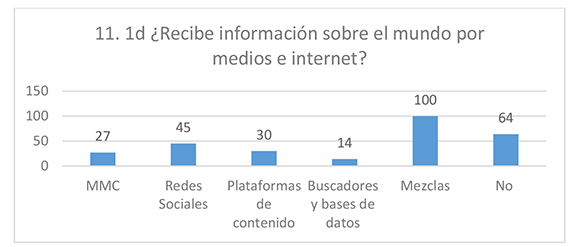

The information on the Armed Conflict in the world constitutes a striking scenario in the media and informational field (E4). The autonomy of the student to search the media and the Internet is highlighted; the strengthening of investigative competences and informational competencies (source management, information management).

Graph 7. Breakdown of the Media and Information Scenario (E4)

4.3.3.2. Armed conflict in Colombia

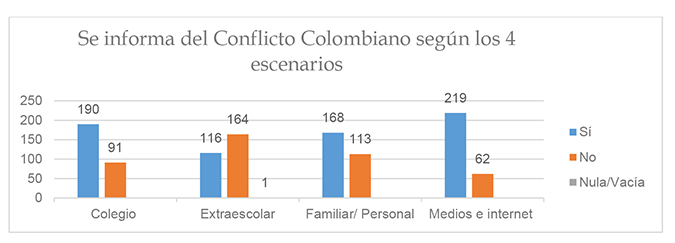

The students, in their great majority, are informed about the Colombian Armed Conflict through the media and the Internet, which is consistent with the acceptance that the NICT have with young people (motivational factor and age).

Graph 8. Colombian conflict according to the four scenarios

The breakdown of the 190 responses of the School Scenario (E1) is determined by: school subjects (146 cases), plus lectures, workshops and seminars (22 cases). The mix of subjects and workshops are added (22 cases). In the Extracurricular Scenario (E2), the ‘No’ prevails as an answer (164 cases), while the remaining 116 cases are determined in: neighborhood, libraries, church, museums. The breakdown of the Family / Personal Scenario (E3): 113 cases in which the information is received in the family (grandparents, parents, siblings, cousins, etc.); in 25 cases the friends influence; in 30 cases the two environments are mixed and there are 113 cases in which the students answer ‘No’. There is a difference in the interest for information of a global nature with respect to the national: it does not have the same meaning, importance or motivation. Finally, it is the Media and Informational Scenario (E4) that motivates the highest frequency of use. Of the 219 cases (77.93%) that declare to go to this environment, 48 use the MMC (traditional media: press, radio, TV), 39 go through Social Networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram); 25 through Content Platforms (You Tube, Wikipedia, others) and 14 through search engines and databases. The importance is represented as follows

Armed Conflicts the world: E4 > E1 > E3 > E2

Once again, the breakdown by the 4 demarcated scenarios indicates that the information is obtained, mainly through the Media and Information Scenario (E4), followed by the School Scenario and the Family / Personal Scenario. The Extracurricular Scenario (in which the interaction is less) is the last of importance.

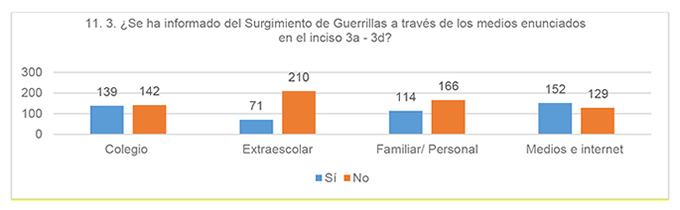

4.3.3.3. Emergence of Guerrillas and Insurgency in Colombia

74.73% of the population says ‘No’ to be informed about this topic. This disinterest changes only in the Media and Information Scenario (E4), in which this gap in mediation is once again overcome (call school, out-of-school, family / personal mediation). Within the E4 it is observed that the MMC (Traditional media) is more important in this topic: 38 cases, followed by the Content Platforms: 32 cases, the Seekers and Data Bases and finally the Social Networks: 17 cases. When analyzing the scenarios in which the ‘Not reported’ on this subject prevails, the result has been negative.

Graph 9. Emergence of Guerrillas according to the four scenarios

The breakdown in the School Scenario (E1) shows: Of the 139 ‘Yes’, 123 cases are presented in which the information comes directly from the compulsory subjects of basic and secondary education. The Extracurricular Stage (E2) shows 65 cases (of 71 registered), in which they state that the information comes from the Neighborhood, the Libraries and some from Museums. Similarly, in the (E3) Family Scenario (87 cases) / Personal (16 cases), mixed: 11 cases to indicate that the lack of communication around this issue is evident in the 166 students who say ‘No’ to speak of this subject in your family or personal environment. This leads to a single area E4 with 152 cases in which the search for information and learning occurs through traditional means of communication and the means derived from the Internet. It is concluded that the obtaining of information prevails through the Media and Informational Scenario and the responses of the ‘Not reported’ prevail, which is expressed as follows: -E2> -E3> -E1. This subject is presented as forbidden in the extracurricular setting. To a lesser extent by the school and the family. The representation (excluding the negatives) is reduced to:

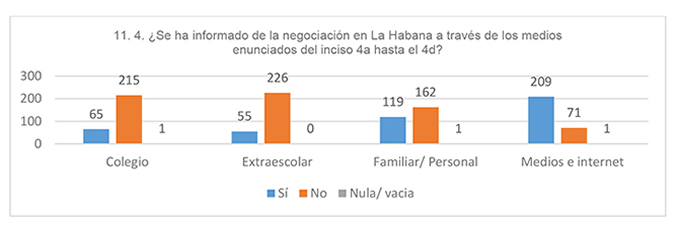

4.3.3.4. Negotiation and the Agreements in Havana

When we talk about specific information, the data show the ignorance on the part of the students. Neither the School Scenario (E1) nor the After School (E2) represent environments for learning or interaction around this topic. In (E3) 42.34% of young people say they talk about the Negotiations and the Agreement in Havana and 57.65% declare not to receive information about it and this despite being one of the most important and decisive facts in the history of Colombia in 2016.

Graph 10. The Negotiations of Havana according to the four scenarios

It will be again the Media and Information Scenario, E4, which privileges the choice of information search of young people. The 209 cases in which they are reported are broken down as follows: Mass Communication Media (57 cases), followed by Social Networks (39 cases); Searchers and BBDD (19 cases) and content platforms (17 cases). The responses of the ‘Not reported’ on the Negotiation and Agreements of Havana evidence: -E3> -E1> -E2. The representation (excluding the negatives) is reduced to:

Negotiations and agreements en Havana: E4

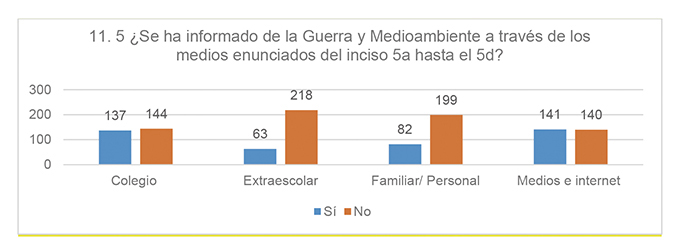

4.3.3.5. War and Environment

This scenario evidences a turning point of the information. The average of the ‘No’ begins to impose itself on the ‘Yes’. One of the main problems arising from the armed conflict has been the ‘attacks on oil pipelines’, the first of which can be referenced in 1965, “against an oil pipeline of the Cities Services Intercol, near Barrancabermeja”, according to Issa Tejada. (2015, p.6), who affirms that between 2000 and 2014 the Ministry of National Defense reported 1,841 attacks against the pipeline network in the country, which has been of enormous economic and environmental importance. It has been disseminated through the media, but the young people surveyed say they are ignorant and lack interest in this topic. The predominance of the response is ‘Not reported’ on this subject, but the reader can appreciate the polarization of results present in the media and information Scenarios (E4) and the School Scenario (E1).

Graph 11. War and Environment according to the four scenarios

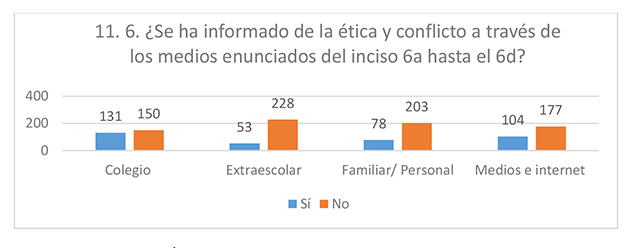

4.3.3.6. Ethics and armed conflict

The predominance of answers that show the thematic ignorance on the part of the students keeps on increasing. Information scenarios are not privileged, we only have an approach to information from the School Scenario (E1) in which the acquisition of information through subjects predominates (131 cases) and a media and information Scenario (E4) in which the young people are provided with information from the multiplicity that technology allows. The ethical issues do not represent importance and / or interest for the young people surveyed and apparently this subject, once privileged in the family, is currently only part of the interest of a few.

Graph 12. Ethics and Conflict according to the four scenarios

4.3.3.7. Constitution and Armed Conflict

Having a new Constitution (1991), which implies the obligatory teaching of the Constitution, greater appropriation of knowledge by the ‘millennial’ respondents is expected. The analyzed data show a predominance in all the scenarios of the answers of the ‘No’ (No Constitution and Conflict have been reported). The Extracurricular E2 scenarios (239 cases show ‘No’) and the Family / Personal E3 (214 cases show ‘No’). However, some representativeness is evident in the two expected scenarios, that is, the E1 (school scenario) for the aforementioned mandatory thematic that is imposed in schools: it contributes 128 cases that answer ‘Yes’, compared to 153 respondents that ‘They are not informed’); and the E4 Media and Information Scenario (105 cases ‘Yes’ versus 175 ‘No’).

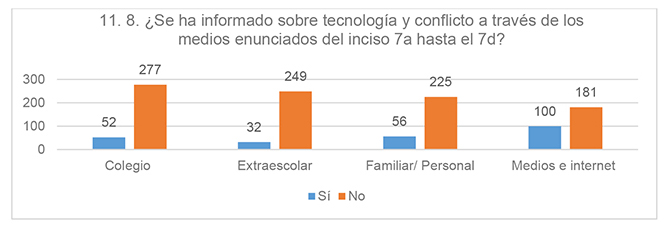

4.3.3.8. Technologies and armed conflict

The ‘No’ trend prevails, which shows a lack of commitment to the current Knowledge and Information Society (SIC) based on the ICT as a tool to generate value and promote developed, inclusive and democratic societies. The path of ICT goes through the Appropriation / Employability / Integration but, as Ferreiro and De Napoli point out, the use of ICTs is a challenge to overcome more in the pedagogical than in the technological. (2008; 338).

Graph 13. Technology and conflict according to the four scenarios

4.3.3.9. Culture, sport and armed conflict

The tendency of ‘No’ prevails, which reveals that traditionally important social areas and their current problems do not arouse interest among a considerable part of the youth. The E1 scenarios (224 ‘No’ responses from 281 respondents); E2 (247 cases ‘No’); E3 (229 cases ‘No’) and E4 (198 cases ‘No’). The respondents reveal a lack of interest in this topic. Which is represented: -E2> -E3> -E1> -E4.

4.3.3.10. Democratic Participation in the Armed Conflict

Finally, the issue of democratic participation and armed conflict reflects the final tendency of responses in which the issue is ignored. Respondents answer ‘No’ according to scenarios like this: E1 (209 ‘No’ cases); E2 (249 cases); E3 (215 cases); E4 (174 cases). The following scenario conformation is produced according to the ‘No’: -E2> -E3> -E1> -E4.

4.4. Objective 4: To know the way in which the student perceives the peace linked to the agreement with the armed groups and their reality. (Questions 9, 12 and 13)

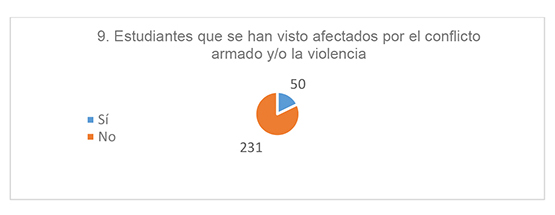

In the first place, it was taken into account if the surveyed population has been affected by actions or actions derived from the Armed Conflict. In this regard it is observed that students perceive peace as a possible process.

4.4.1. Students have been affected by conflict / violence in Colombia

We sought to determine the level of involvement of students with respect to the armed conflict. That is, to determine if their perception was affected by a direct or indirect incidence, or in general terms: what is the level of incidence of the conflict in this school population? It is observed that the number of UAC students affected by the armed conflict and / or violence in Colombia is not relevant to affirm that this fact is taken into account in a correlational analysis of knowledge or perception of peace. The data indicate that 17.8% of the respondents have been affected by the armed conflict; these ‘affected’ come mainly from the Atlantic (30); Bolivar (5); Magdalena (4); Sucre (2) and so on in numbers of a 1.

Graph 14. Level of incidence of the conflict in the students of the UAC

The 50 respondents express their perception of how they have been affected by the conflict: a) directly (experience) 231 cases; b) indirectly (10 of the 50 respondents), the latter have not been affected in the personal or family sphere but perceive that the situation affects them: “I think we have all been affected by this conflict as it leads us to an inequality always “(Survey N ° 21). Those directly affected state that this has been due to:

1. Actions of the guerrilla (Survey N ° 31: “Political uncle brother kidnapped by the FARC”)

2. Actions of paramilitaries (Survey 3: “My grandfather was killed by paramilitaries, by vaccines”)

3. Other forms of violence (Survey N ° 49: “Well, not because of the armed conflict, but because of the violence itself, as because of the bandits in Colombia, an uncle was a victim of them”)

4. Armed actions not manifest or explicit (Survey N ° 45: “My grandmother is a victim of the armed conflict.

5. Actions of relatives at the service of the State and / or of NGOs. (Survey N ° 47: “My father belonged to the Police and in a confrontation that there was with an armed group, he lost one of his legs because of a grenade”).

Finally, note that the data was crossed to see if the perception and / or experience of the conflict affects gender. In this regard it can be said that there is no relationship.

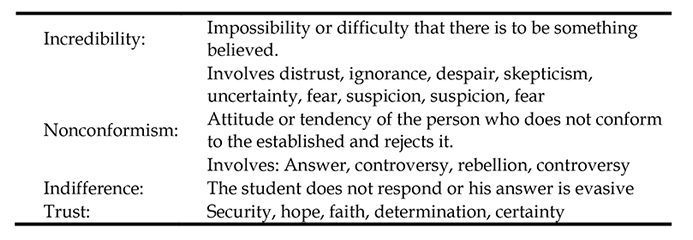

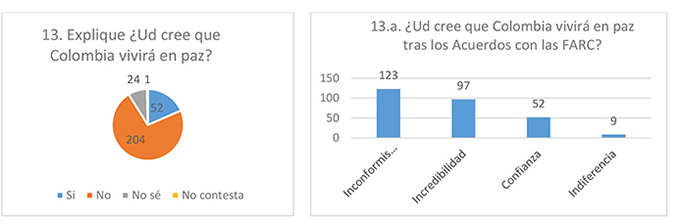

Before the question: Are you believes that Colombia will live in Peace after the Agreements?, the qualitative analysis involved the review and coding of the students’ responses with the consequent creation and definition of categories, namely:

Table 4. Categories according to the analysis of the open question

Graph 15. Perception after peace agreements. Categories

5. CONCLUSIONS

A descriptive study with constructivist design was carried out that focused on the meanings provided by the participants in order to formulate predictions that contribute to the methodologies and / or ways of approaching the subject Society and Culture for Peace, from the perspective of a flexible curriculum. In the general framework of the project in which this study is inscribed, this first phase of the research constituted a diagnosis that will be complemented with phase 2, in which the syllabus of the subject will be revised to formulate a curricular proposal from a flexible perspective, that addresses the challenges of the University and of the students as a representative population group of the Colombian Caribbean in the face of the Post-Conflict in the 21st century.

The students enrolled in 2016/01 in the subject Society and Culture for Peace make up an age group between 17 and 24 years, in which the male sex predominates (54.09%). These are young people who come mainly from the Caribbean Region and particularly from the Department of the Atlantic (202 respondents). 61.2% of them studied in private schools (95 private lay schools and 77 confessional schools: 172 cases) and 34.52% in public schools (97 cases), located in strata 3 and 4. The survey confirmed the initial hypothesis: students have a low level of knowledge, in general terms. It was determined that they have greater strengths in terms of knowledge of the history of Colombia (57.02%); very low strengths around issues such as the inclusion of armed groups in the political life of the country (40.1%). In that order, they have less knowledge about the Negotiation and Agreements of Havana (27%). It is recommended then to influence the issues related to the origin of the conflict, to reinforce issues about the History of Conflicts in Colombia from plural perspectives taking into account characters, spaces and relevant events to strengthen their competences. At the same time, strengthen the interest to know about the current Peace Accords. This is to act in coherence with the university vision of the UAC to form global citizens and provide a transcendent and integrating vision of the culture of peace from the history of the country, understood as critical awareness formation; as a construction of national identity and as a memory of the conflict for the construction of peace.

The way they have acquired the information about the Conflict confirms the second hypothesis: the ‘millennial’ inform themselves and reinforce their learning from two sources: the Media and Informational Scenario -mainly Social Networks and Content Platforms- and the school subjects. This research evidenced that the mechanisms and channels of information that the student has to know the current conflict in Colombia are based on several scenarios that are hierarchized as follows:

– Media and information scenario in which MMCs have been displaced by the use of the Internet, prioritizing the use of Content Platforms (YouTube, Blogs, microblogs) and Social Networks (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram). There is a level of development of digital and research competences, although at a general and non-specific level.

– School scenario in which information is obtained through the compulsory subjects that cover these topics: Social Sciences, Political Sciences, Citizen Competencies, Culture for Peace, Democracy, Economy, Ethics and Values, Philosophy, Geopolitics, History, History of Colombia , History and Democracy, History and Geography, Politics. There is no mainstreaming or interdisciplinarity in the school curriculum.

– You do not perceive interdisciplinarity. The ‘No’ students have been told about the Current Armed Conflict (41.99% of respondents). The school scene does not go beyond the school: you do not go to libraries, museums, etc., as places to build an educational society.

The decentralization of the School Scenario and the decline of the Family Scenario as a source of knowledge became evident. Scenarios traditionally designated as “... the basis of socialization and the transmission of knowledge”. The predominance of the Media and Information Scenario was evident. As Martin Barbero points out

“... both the school and the family are going through the same crisis that erodes the great institutions of modernity, are the media and information technologies - ... - those that are socializing adolescents, since these are the means that currently provide models and patterns of behavior, including rites of initiation that, if they have a lot of cheating and frivolity also have a lot of empathy with a new sensibility that neither the family nor the school seem to want to understand, unable to decipher it let alone take care of it. (2009; pp 22-23).

This places us in front of the need to use researches like the present to rethink the subjects, the teaching-learning models and the role of the teacher. What leads us to anticipate that in a second phase of research, the review of the syllabus of this subject will provide inputs that demonstrate the way in which messages are received with the aim of strengthening the culture of peace in the UAC. It is also remembered the need to involve the teachers of the Humanities Department so that in the subjects of the Institutional Basic Area: Entrepreneurship, Bioethics and Environment, Sports and Culture, Constitution and Democracy, and Language and Communication, the component Transversal on Peace and Post-Conflict is reviewed.

While the student population surveyed is not marked by violence, 17.28% of students say they are or have been affected by the Armed Conflict directly and indirectly. The third hypothesis is observed from the perception that the ‘millennials’ have about peace after the Agreements: Few students perceive peace with hope, their answers oscillate to categories that express: Inconformism, Incredibility and Indifference. Although the hypothesis indicated that young people perceived peace as a possible process, this seems to obey the expectations that teachers have regarding youth. The reality of this survey shows a youth that does not know its history and, consequently, is immersed in nonconformity, disbelief and indifference to their reality and environment. This is where the University must assume a greater commitment and listen to the voices and learning experiences of young people, bearing in mind that young people do not know enough about their history or their current reality and the appropriation is weak - and general. It is required that teachers and university community of the UAC consider strengthening strategies with the use of ICTs as the scenario that represents the greatest interest for them and a tool with great informative and interaction potential (Content platforms and Social Networks). In front of the teachers of the UAC -’digital migrants’ and affected by the armed conflict throughout all their lives-, we find ourselves with ‘digital native’ students who do not know the roots of the problem and consequently do not count (nor can they count) with emotional tools that allow them to believe in change (and therefore produce or support it).

In what way, then, does the scenario of social dialogue and intervention with victims of the conflict created by the UAC since 2013 constitute a contribution? The university environment constitutes an important scenario that can interpret the cultural mediations that arise with the technologies. The Autonomous University of the Caribbean must provide these humanistic reflections as a starting point to formulate new methodological approaches and new learning proposals, assuming that “the process of school learning cannot be separated from the exercise of citizenship” (VV.AA., 2012; P. 121). Similarly, the results of this survey will lead, in turn, to revise a new vision for the subject taking into account what young learners think of the 21st century and the way they are directed to build Information and Knowledge Societies. The rapidity with which the UAC implemented the Chair of Peace in the first semester of 2015, invites to bear fruit.

REFERENCES

1. Beltrán WJ, Quiroga JD. Pentecostalismo y política electoral en Colombia (1991-2014)”. Colombia Internacional, 91, 187-212. doi: 10.7440/colombiaint91.2017.06

2. Bustos C, Jaramillo M (2016). ¿Qué tiene que ver con el medio ambiente la paz en Colombia? The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/oct/24/medio-ambiente-paz-colombia

3. Delors J (1997). La educación encierra un tesoro: Informe a la UNESCO de la Comisión Internacional sobre la Educación para el Siglo XXI. México: Correo de la Unesco.

4. Ferreiro R, De-Napoli A (2008). Más allá del salón de clases: los nuevos ambientes de aprendizaje. Revista Complutense de Educación, 19(2):333-346

5. Freire J, Brunet K (2010). Políticas y prácticas para la construcción de una Universidad Digital. La Cuestión Universitaria. Boletín Electrónico de la Cátedra UNESCO de Gestión y Política Universitaria, 6. Monográfico: “Políticas universitarias para una nueva década, 85-94.

6. Issa-Tejada LF (2015). Efectos del terrorismo en los oleoductos de Colombia (2000-2015) (ensayo de Especialización). Recuperado http://repository.unimilitar.edu.co/bitstream/10654/7789/1/EFECTOS%20DEL%20TERRORISMO%20EN%20LOS%20OLEODUCTOS%20DE%20COLOMBIA.pdf

7. Kulesz O (2017). La cultura en el entorno digital. Edita UNESCO.

8. Martín-Barbero J (2009). Cuando la tecnología deja de ser una ayuda didáctica para convertirse en mediación cultural. Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, 10(1):19-31.

9. Morales V (2016). Proyecto de Ley Por el cual se modifica parcialmente la Ley General de Educación, Ley 115 de 1994, y se dictan otras disposiciones. Recuperado de http://leyes.senado.gov.co/proyectos/index.php/textos-radicados-senado/pl-2015-2016/596-proyecto-de-ley-166-de-2016

10. Pérez-Tornero JM, Varis T (2010). Alfabetización Mediática y Nuevo Humanismo. Editorial UOC

11. Post-truth (2017). Oxford Dictionary on line. Oxford University Press. Recuperado de https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/post-truth

12. Prensky M (2001). Digital natives, Digital Immigrants. Part 1, On the Horizon, Vol. 9 Issue 5, pp 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

13. Revista Semana. (11 de febrero de 2017). Colegios podrían enseñar Historia como una materia independiente. Recuperado de http://www.semana.com/educacion/articulo/clases-de-historia-en-colegios/515072

14. Santos C (2016). Cultura de paz, educomunicación y TIC en Colombia. Opción, 32(12):609-637.

15. UAC (2016). Informe de Condiciones Iniciales Universidad Autónoma del Caribe.

16. UNESCO (2005). Hacia las Sociedades del Conocimiento. Informe mundial de la Unesco. Paris. Ediciones UNESCO.

17. Vargas R, Santana J (2015). Uniautónoma, academia para la paz. Barranquilla: Editorial Uniautónoma

18. VVAA (2014). Uniautónoma Academia para la Paz. Barranquilla, Colombia.

19. VVAA Coordina: Sofía Coca (2012). Educación Expandida. Edita: Zemos 98.

AUTHORS

Clara Janneth Santos-Martínez

Social communicator-journalist at the Bucaramanga’s Autonomus University (Colombia), Dr. in Communication Sciences (Complutense University, Madrid, Spain) Investigator teacher at Social & human sciences faculty, Caribbean autonomous university UAC (Colombia); Member of the research group “Interaction of Educational Potentials, Communication and Region”

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9526-4177

Jennyfer Solano Betancourt

Social communicator-journalist in training, with experience in the journalistic field and investigation. Research seedbed “Senior” in the group “Communication and region” Carribean autonomus university (UAC)

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0210-2097

Sergio Samuel Nieves Vanegas

Mathematics & phisycs degree, University of the Atlantic (Colombia), Applied statistic Magister by University of the North, candidate Doctor in Sciences mention Management by the URBE (Venezuela), Full time teacher at the Carribean autonomus university (UAC, Colombia) Basic Sciences department, member of the research group GMA.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5000-0445