doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.149.91-108

RESEARCH

ANALYSIS AND REGULATION OF LOBBYIN THE EUROPEAN UNION

ANÁLISIS Y LA REGULACIÓN DEL LOBBY EN LA UNIÓN EUROPEA

ANALISES E A REGULAÇÃO DO LOBBY NA UNIÃO EUROPEIA

Ana Belén Oliver González1

1Complutense University of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

There are currently thousands of lobby groups registered in Brussels. The registration of lobbies in the EU is voluntary, it does not establish penalties for those groups that decide not to do so. Determinant factor in the policy of transparency and ethics in the decision-making process. The lobby is an opaque activity by its very nature, which although necessary for the exercise of democracy, is mediated by the handling of information -sometimes in a privileged way- that reduces the democratic maneuverability of actors who in themselves have not been elected for the position they occupy and are more susceptible to pressure. The general objective of this study is to analyze the regulation of the lobby in the EU. The specific objectives are to describe the main characteristics of lobbies in community institutions, identify the community regulatory framework for the exercise of lobbies in these institutions. Lobby regulation has been more a political response to citizen disaffection than a measure of institutional coercion. There is no homogeneous framework for evaluation or restraint that is not susceptible to violation by the permanent lobbyist army in Brussels, nor is there a single framework in each State. These are, in general, novel mechanisms to regulate a trade that until it did not emerge as part of the 2008 crisis was not a problem; on the contrary, it is still seen as a fundamental part.

KEY WORDS: lobby, regulation lobbies, community institutions, transparency registry, institutional trust

RESUMEN

Actualmente hay miles de grupos de lobbies registrados en Bruselas. El registro de lobbies en la UE es voluntario, no establece sanciones para aquellos grupos que decidan no hacerlo. Factor determinante en la política de transparencia y ética en el proceso de toma de decisiones. El lobby es una actividad opaca por su propia naturaleza, que aunque necesaria para el ejercicio de la democracia, está mediada por el manejo de información –algunas veces de forma privilegiada– que reducen la maniobrabilidad democrática de actores que de por sí no han sido electos para el cargo que ocupan y son más susceptibles a presiones. El objetivo general de este estudio es analizar la regulación del lobby en la UE. Los objetivos específicos son describir las principales características de los lobbies en las instituciones comunitarias, identificar el marco regulatorio comunitario para el ejercicio de lobbies en dichas instituciones. La regulación del lobby ha sido más una respuesta política a la desafección ciudadana que una medida de coerción institucional. No existe un marco homogéneo ni de evaluación ni de sujeción que no sea susceptible de vulneración por parte del ejército lobista permanente en Bruselas, como tampoco hay un marco único en cada Estado. Se trata en general de mecanismos novedosos para regular un oficio que hasta no emerger como parte de la crisis de 2008 no constituyó un problema; muy por el contrario, sigue siendo visto como parte fundamental.

PALABRAS CLAVE: lobby, regulación lobbies, instituciones comunitaria, registro de transparencia, confianza institucional

RESUME

O registro de lobbies na EU é voluntario, não estabelece sanções para aqueles grupos que decidam não o fazer. Fator determinante na política de transparência e ética no processo de tomada de decisões. O lobby é uma atividade opaca por sua própria natureza, que apesar de necessária para o exercício da democracia, esta mediada pelo manejo de informação – algumas vezes de forma privilegiada – que reduzem a manobralidade democrática de atores que por si mesmo não foram eleitos para o cargo que ocupam e são mais susceptíveis a pressões. O objetivo geral deste estudo é analisar a regularização do lobby na EU. Os objetivos específicos são descrever as principais características dos lobbies nas instituições comunitárias, identificar o marco regulatório comunitário para o exercício de lobbies nas citadas instituições. A regularização do lobby foi mais uma resposta política à insatisfação da cidadania que uma medida de coerção institucional. Não existe uma referência homogênea nem de valoração nem de sujeição que não seja susceptível de vulneração por parte do exército lobista permanente em Bruxelas, como tampouco há um marco único em cada Estado. Se trata em geral de novidades de mecanismos para regular um oficio que até não emergir como parte da crise de 2008 não constituiu um problema; muito pelo contrário, segue sendo visto como parte fundamental.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: lobby, regulamento lobbies, instituições comunitárias, registro de transparência, confiança institucional

How to cite the article: Oliver González, A. B. (2019). Analysis and regulation of the lobby in the European Union. [Análisis y la regulación del lobby en la Unión Europea]. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, (149), 91-108.

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.149.91-108

Recovered from http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1107

Correspondence: Ana Belén Oliver González. Complutense University of Madrid. Spain. anabeleo@ucm.es

Received: 16/11/2017

Accepted: 21/05/2019

Published: 15/12/2019

1. INTRODUCTION

There are currently thousands of lobby groups registered in Brussels, of different types and diverse backgrounds, from sectorial business groups, environment defenders, foreign foundations, to the so-called para-diplomacy of regions and factions of territorial institutions of Member States.

This kaleidoscope of interests and pressures of specific groups is by no means new, although the transparency and regulation processes promoted by various sectors to legalize the de facto work carried out by the lobbies are novel indeed, since it is from 2008 on that a Registration in Brussels about these groups is going to start, and their implementation will be carried out starting in 2011, in the three main community bodies susceptible to lobby: the European Commission, the European Council and the European Parliament.

The European Commission, hereinafter, estimates that more than 2,500 professional lobbies come to life in Brussels , with a lobbying “army” that can reach more than 20,000 people; its presence stands out from 1992 on with the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty, although its origins would be informally and residually in the mid-seventies of the twentieth century, which acted without regulations and that their work turned out to be more opaque, for being the diplomatic lobby, the one which exercised the leading role in the European capital.

The registration of lobbies in the EU is voluntary, that is, it does not establish penalties for those groups that decide not to do so. Hence, the main critics establish different parameters to calculate a specific number, since such a record does not reach the 8,000 lobbyist groups targeted. This factor is decisive in the policy of transparency and ethics in the decision-making process of the community institutions.

On the other hand, Catalonia (Spain), Scotland (United Kingdom) Lower Saxony (Germany) or Venice (Italy), among others; they are territorial regions of their countries with permanent offices in the European capital to press for their domestic interests and persuade in the decision-making process, either in the European Parliament, in the European Council, or in the European Commission, where they exercise a strong lobby towards financing community projects or against policies that are sensitive to their economies such as the CAP (Common Agricultural Policy).

While the Commission is leading the communication initiative in Brussels, and the Parliament with its headquarters in Strasbourg settles the entire European political arch - and its assistants, offices, bureaucrats and the lobbyist behind it - it is the European Council that requires much more professional lobbying delicate work, due to its High Representation and the definition of the agenda that occurs within it.

Much less mediatic but at greater risk, the European Council is the highest representative office of the EU, so its president is subject to huge pressures from various and varied actors (from the States themselves, from the other EU institutions, of the inter-agency interests of the EU, of the territories of the States, of the global business groups, of the international organizations, etc.) and given the kaleidoscope it serves, its decisions are subject to the satisfaction of its members , that is, it has factual limitations to satisfy many competing interests.

Lobby is an opaque activity by its very nature, which although necessary for the exercise of democracy and rights, is mediated by the handling of information - sometimes in a privileged way - that reduces the democratic maneuverability of actors that have not been elected to the position they occupy, that is, they are more susceptible to the pressures of those who served as their constituents. With this in mind, the EU has been making significant progress to reduce such pressures in its community bodies.

2. OBJECTIVES

The general objective of this study is to analyze the regulation of lobby in the EU institutions.

The specific objectives are to describe the main characteristics of lobbies in community institutions, defining the community regulatory framework for the exercise of lobbies in these institutions.

3. METHODOLOGY

The development of the research is approached following the premises of the comparative method for research, by means of which a contrast is made among the communicative actions, the regulation and transparency policies, and the persuasive policies that influence the community institutions and member states on the part of the lobbies, observing their characteristics and the applicable regulations within these EU institutions.

The study has been approached from the combination of different perspectives: normative and legal. Although it is true that the degree of intensity with which each one has been worked on has been different, it has been attempted to not leave out none of them out of this study.

From a normative point of view, it has departed from the Treaties of the European Union currently in force, and in particular the Treaty on European Union (TUE), the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and the Treaty of Lisbon. From the legal point of view, we have worked with the laws of the EU member states. The study of these norms and laws has helped to define the present study.

Working with the existing bibliography has already been more complex due to the need to select the one that specifically addresses the notion of lobbies and lobbing in the EU. It is possible to say that the literature on the subject is remarkably wide, but in the majority of occasions we are faced with joint studies that save with a few lines or pages, and without deepening, the object of this study; Analysis of the regulation of lobby in the European institutions. Even so, the work of F. Morata (1995), “Influence to decide: the incidence of lobbies in the EU” has been especially useful, and in a certain way has been followed; E. Alonso (1995), “Lobby in the EU: Manual of good use in Brussels”; P. Bouwen (2002), “Corporate Lobbying in the European Union: The Logic of Access”; J. Xifra (2005), “The think tank and advocacy tank as actors of political communication”; A. Castillo (2009), “The communication of lobbies on the Internet. The cyber-activism of Think Tanks”; R. Calduch (1995) “International Relations” and (2011) “Notes of the European Union”; R. Correa (2010), “Communication: lobby and public affairs”; A. Peña (2011), “Public relations and lobby. Management for transparency”; all of them cited throughout the study. It goes without saying that the contributions of this literature have been complemented by other works and specialized articles extracted from publications, which have been consulted on different websites, whose links are found at the end of the study, in sources used.

The research technique is qualitative insofar as it explains this process based on the definition, characterization and regulations of lobbies in community institutions. A broad understanding of the regulation of lobbies in community institutions is sought with this technique based on their operating structures and regulatory procedures in these institutions in the city of Brussels, Belgium.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Institutional confidence as a legitimizer of lobbying

The political trust places in the institutions and the norms of coexistence, the main vertex of the effective materialization of such trust. The institutional architecture is the basis for the maximization of such a process, therefore a priori trust must produce post-facto trust, a mechanism that maximizes the potential benefits derived from the effectiveness of the behavior of all the institutions.

Institutional trust implies a positive evaluation of the most relevant attributes that make each institution trustworthy, such as credibility, justice, competition, transparency. This confidence is based on the basic idea that it will act in an egalitarian, fair and correct manner in accordance with the binding legal framework.

Lobbyist agents are depositaries and at the same time legitimizers of political confidence in democratic institutions. The rectitude, probity and transparency among them and the political actors are a sine cuan non requirement for the guarantee of the system and specifically, to legitimize socially the exercise of professional lobbying as part of the system.

4.2. Accountability and lobbies in community institutions

Accountability implies that the law applies sanctions to representatives and public officials who incur in omissions, bad practices and abuses of public power. On the other hand, it means that those responsible for the community institutions have to act with reciprocity and efficiently meet the public demands of citizens and the various sectors represented in Brussels. Thus, the demands have to be evaluated based on information, opinions, data and specialized arguments that serve to make rational decisions for the general interest of the population.

Community legislative institutions are particularly relevant for lobbying, since external relations with individuals, interest groups, and lobbies will be exercised from their organization and from the internal rules of procedures and introduction of laws and agreements.

Trying to make the most rational decisions favorable to the general interests of citizens, legislators frame their decisions in the plurality and opposition of interests, requiring the technical assistance of specialists, professional agents with access to specific sectors outside the public official, that is, the participation of lobbyists is required.

This way, the regulation of lobbying is related to the quality and depth of democracy. The institutional interaction between the State and the agents-actors of civil society are definitely the mechanisms to avoid the absence of ethics, opacity and potential corruption of the lobbyists in their professional practice.

4.3. Regulation of lobbies in the European Union

Since the creation of the ECSC - predecessor of the EEC - there have been in Brussels the presence of lobbies tending to influence its decisions informally. Francesc Morata observes that this was welcomed by the Europeanist political leaders when considering them a way to facilitate the process of adherence of all national institutions in the European framework.

The “founding fathers” and neo-functionalist theorists, such as Haas and Lindberg, attached crucial importance to the development of stable relations between the economic and social elites of the Member States and the high authority of the ECSC (predecessor of the European Commission)----- in order to put pressure on governments and create the necessary loyalties to deepen the integration process until it becomes irreversible. (Morata, 1995, p.131)

It will be in the framework of the role of non-state actors in the process of European integration and the interests around the community interest model that the necessary bases for discussions will be created, especially in the so-called Single European Act of 1983, when lobbies are given special attention before the obvious but unregulated influence they had on the laws and guidelines that came out of the Commission. Jordi Xifra affirms that “European institutions since their beginning have been under the pressure of industrial groups, services, law firms that yearned for a particular and interested perspective to appear in the community norms”. (Xifra, 2000, p. 175)

The reasons for lobbying in Brussels are innumerable. A basic reason lies in the fact that obvious gains or losses in terms of regulations, financing or influence are at stake. At the same time, the very complexity of the decision-making system, more organizationally fragmented, less hierarchically integrated and more competitive than national systems, offers much greater accessibility to organized groups. (Morata, 1995, p. 130)

The EU institutions have now coordinated actions in relation to lobbyists such as lobbies in two ways: through informational transparency around EU relations with various groups; and on the other hand, through a Code of voluntary good practices for lobbies to guide their behavior through it. All this supported in the framework of community law.

The Treaty of Lisbon of 2009 establishes that “the institutions will give citizens and representative associations, by appropriate channels, the possibility of expressing and publicly exchanging their opinions in all areas of action of the Union” being that the community institutions themselves “They will maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society” (art. 2). Continues in its art. 136, b, saying that the EU “will recognize and promote the role of the social partners in their field”, so it will facilitate a dialogue between them, while respecting their autonomy. (Treaty of Lisbon, 2009).

However, the work on the relationship with actors and interests of the European civil society has been developed before. In 2006, the European Commission published the Green book on European Transparency, following a meticulously elaborated work by the European Commissioner for Administration, Audit and Anti-Fraud Control, Siim Kallas between 2004 and 2005. In the Green book, the Commission itself defines lobbying as,

A legitimate part of the democratic system, regardless of whether this activity is carried out by individual citizens, companies, civil society organizations as well as by other interest groups or even firms that work on behalf of third parties, as responsible of institutional relations, “think-tanks” or lawyers. (Europe Union, 2010).

For the Commission, civil society organizations play a liaison role between citizens and European institutions by promoting a political dialogue and an active participation of citizens in achieving EU goals, so their role is fundamental to legitimize the institutional work of the block. However, the European Commission classifies interest groups into non-profit organizations (associations, European, national and international federations) and for-profit organizations (legal advisors, public and private companies and consultants). “The first ones are, to a large extent, but not exclusively, professional organizations. The latter are people who usually act on behalf of third parties to define and defend their interests”. (Álvarez and De Montalvo, 2014, p. 370).

4.4. Literature review on lobbies

The literature on lobby, lobbying and its imprint on political systems is subject to the historical revision of Anglo-Saxon parliaments, with special deference in the case of the United Kingdom and the United States as sources originating from the current professional practice of lobbying.

These are empirical studies, contextualized on topics of socio-political interest and therefore constrained in space and time to the dynamics foreseen in it. The focus of the current analysis, however, is focused on the dimensions of democracy and citizen participation in it, related to the mechanisms of transparency, accountability and access to public information, mechanisms that have questioned some of the actions taken by groups of pressure within civil society.

Given the nature of lobbies, their literary linkage comes as an added component of the causes, consequences and/or impact that they produce in international, regional and local dynamics, especially linked to regulatory processes, such as the case at hand around the community institutions.

4.5. Registration of lobbies in the EU

In the summer of 2011, an agreement between the European Parliament and the European Commission for the establishment of a “Transparency Register for organizations and self-employed persons participating in the development and implementation of the ”European Union policies”, whose scope will be to register all activities carried out“ in order to directly or indirectly influence the processes of elaboration or implementation of policies and decision-making of the institutions of the Union, regardless of the channel or medium of communication used, ”states the Agreement. (Join Transparency Register Secretariat, 2012)

In this same sense, the European Parliament approved in 2012 a “Code of conduct of the Members of the European Parliament on economic interests and conflicts of interest” where its parliamentarians must record on the income from activities remunerated outside the Chamber, in line with the provisions of 2011 and following the policies initiated in 1996.

This 2011 registration between the Parliament and the Commission is voluntary, based on transparency and rapprochement with the citizen that the EU fosters, legitimizing and reinforcing ethics in the decision-making process while reinforcing (or trying) the information available around the interests that occur around community institutions.

It contains a code of conduct or good practices that the EU considers necessary to legitimize the work of these groups, who in the opinion of the Commission are legitimate representatives of the civil society and sectorial interests of the various unions and sectors in the EU. This register indicates that the registered groups must:

At the end of 2012, in the middle of the global financial crisis, and especially, in the face of the debt crisis in the countries of southern Europe (Greece, Portugal and Spain, plus Ireland), the Public Registry had 5,362 organizations, classified as:

Citizens can and should expect the EU decision-making process to be as transparent and open as possible. The greater the openness, the easier it is to ensure a balanced representation and avoid abusive pressures and illegitimate or privileged access to both information and decision makers. Transparency is, in turn, a key element in promoting the active participation of European citizens in the democratic life of the EU.

The Transparency Register has been created to answer basic questions such as what interests are pursued, who defends them and with what budget. The system is jointly managed by the European Parliament and the European Commission. (Registro de Transparencia, 2016).

4.5.1. 2012 Transparency Registry Report

The joint Secretariat of the Parliament and the Commission prepared the first annual report of the EU Public Transparency Register where they accounted for the few more than 5400 organizations that registered in that first year of operation.

They point out that, in accordance with Article 11 of the TEU, the EU institutions are open to the contribution of citizens, representative associations and the civil society, guided by the participatory democracy scheme advocating their actions.

They point out that the Transparency Registry is a kind of “unique window” for citizens to exercise their right to be informed, knowing the influences that occur in the decision-making process at the different community levels.

Through this simplified registration process, registered entities undertake to respect a code of conduct that covers compliance with legal requirements and ethical principles. Since its inception, an open invitation has been extended to the Council to join this scheme and to all other bodies of the Union that use it as a reference instrument. Registered entities provide the most essential information about themselves: community legislation makes an effort to estimate the financial mobilization that this pressure implies, from the costs of the offices, the people involved, members or customers, as well as the amount of EU funds they have received. (Informe Anual, 2012, p. 4).

During that first year, the Secretariat confirmed a modest advance in the proposed objectives, especially by the technical coordination established between the Parliament and the Commission for the implementation of the electronic platform and in real time of the total combined registration that both institutions carried out separately. Thus, the 2012 Report indicates that the objectives achieved for that year were:

Finally, the Transparency Register Board affirmed that the platform implemented worked well at the end of the first year, where the EU institutions and bodies have been coupling to the operation of the system, which caused expectations to increase and objectives and goals to be set were aligned with it. Some of these are to improve content, procedural rules, requests for records; to increase external communication so that the registered organizations continue to grow; make available to the labor staff of the Parliament and the Commission the guidelines of the Register through training programs with the possibility of extension to the whole of the EU. It concludes conclusively: “The scheme will only be fully effective if the Members and staff of the institutions share the responsibility of promoting its use in their contacts and interaction with third-party organizations”. (2012, p. 3).

The Board notes in its 2012 Annual Report of the EU institutions as a whole so that the transparency and control of the work and activism of pressure groups and lobbies is in line with the ethics and accountability assumptions of the officials that are part of it.

One of the explanatory keys of the activism of lobbies at European level resides in the hybrid character of the community system. Without being a State in the strict sense, it has, however, one of the fundamental characteristics of any State: the necessary authority to make mandatory assignments to the society in the form of regulatory, distributive and redistributive policies (Mazey and Richardson, 1994). With an appreciable budget, the EU adopts mandatory decisions both by national administrations and by companies and individuals in the fifteen Member Statesmbros. (Morata, 1995, p. 130).

The results seem to indicate that the road ahead is still very long, especially when organizations such as International Transparency place in a very mediocre position the efficiency of the EU in particular and of all the countries that compose it in general, in terms of the transparency and regulation of pressure groups and the lobbies that live in them.

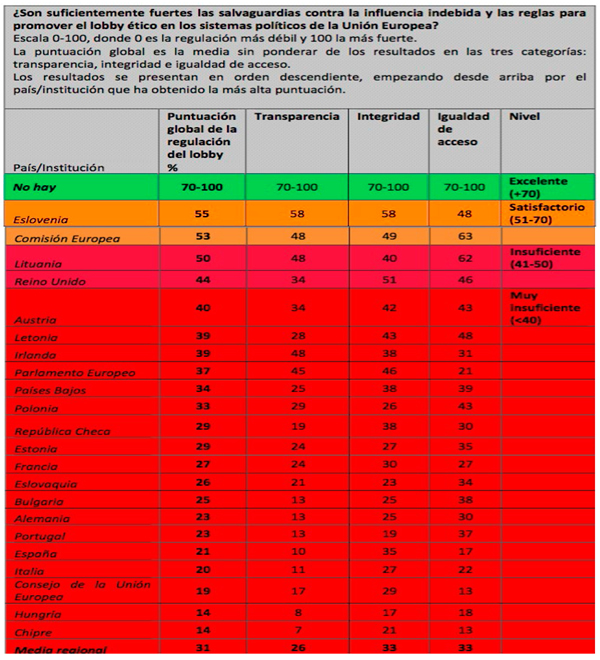

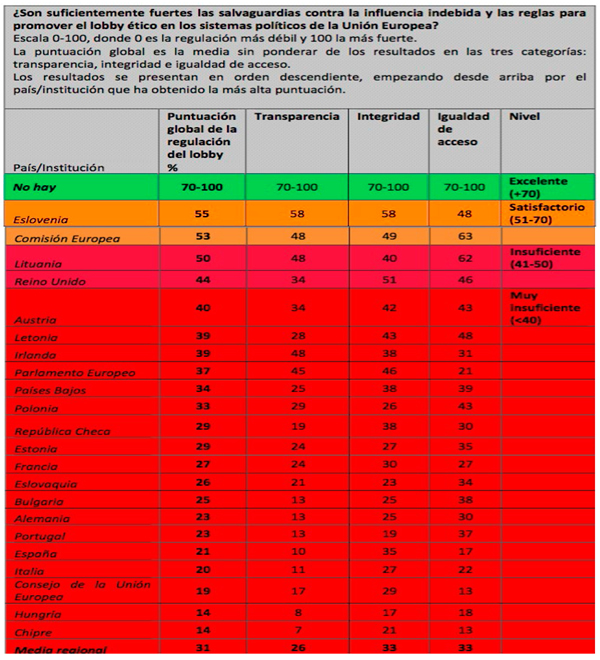

Table 1. EU guarantees and safeguards against the Lobby.

Source: International Transparency (2015) Lobbying in Europe, online.

In accordance with this table, Slovenia, and the European Commission, obtain an approval in the investigation of the organization Transparency International (a score of more than 50% in the established measurement model). Despite the latter, the report notes some legal gaps, reduced regulatory frameworks and delays in the application of some regulations and procedures.

Unfortunately, the third from last place occupied by the European Council, which according to Transparency International has a great decision-making capacity but poor performance in regulating the pressure groups and lobbyists in its environment. This NGO grants 19%, almost half of the regional average of 31%.

Similarly, highly indebted countries that required international and European financial assistance due to the global recession crisis 2008/2012 occupy the worst places in that index (Cyprus, Spain, Italy and Portugal).

5. CONCLUSIONS

The EU has sufficient resources and skills to attract the attention of organized groups. Its decisions are relevant in many ways for economic, social and territorial interests. But its administration and technical procedures have made it a fragmented organization, atomized between committees, groups, agencies and networks; therefore, different groups have greater opportunities for access to key centers, and in particular to the Commission, throughout the decision-making process and even during the implementation phase of the policies and resolutions adopted.

Lobby regulation has been more a political response to citizen disaffection than a measure of institutional coercion. The (re)legitimization of political systems through a set of legal reforms on transparency, accountability and access to information have been basic pillars of political changes in community institutions.

In this area, there is a change in the trend regarding the legal treatment of lobbies, so in the face of the silence that most legal systems maintained on this phenomenon, with the exception practically of Germany, we have moved to a situation in which a large number of States have already introduced or initiated the regulation of the activity carried out by such groups.

Most of these regulations respond to a less demanding model in which the main element of it is the voluntary registration, of the individuals and groups by which they must register in order to develop their activity in a professional, legitimate and lawful manner. This formula contrasts with that approved in other non-European States, such as the United States of America or Canada that have incorporated a model that for years has been evolving towards more rigorous formulas to control lobby activity.

In the case of community institutions, there is a high degree of participation of national administrations and the groups organized in the political process, debates and parallel forums that take place in daily life. The expansion of capacities and functions after Lisbon 2009 has forced the agreement between the community institutions, governments and other political, economic and social actors involved as fundamental elements of the EU’s operation in an exercise of institutional and citizen co-responsibility.

However, the path to transparency is not the same for the EU institutions. The Parliament and the Commission take the lead in terms of transparency and accountability for citizens. The European Council is the most “opaque” body in its decision-making process, since its huge related bureaucratic network of more than 10,000 officials is the center of interest for lobby groups and third parties engaged through them.

There is, therefore, no homogeneous, nor evaluation or restraint framework, that is not susceptible to violation by the permanent lobbyist army in Brussels, nor is there a single framework in each of the 27. In general, these are novel mechanisms to regulate a trade that until it did not emerge as part of the 2008 crisis, it was not a problem; On the contrary, it is still seen as a fundamental part of the exercise of civil society in requesting the State for its sectorial interests.

REFERENCES

1. Alonso Pelegrín, E. (1995). El Lobby en la Unión Europea: Manual Sobre el buen uso de Bruselas. Madrid: ESIC.

2. Álvarez, M. y De Montalvo, F. (2014). Los lobbies en el marco de la Unión Europea: una reflexión a propósito de su regulación en España. Teoría y Realidad Constitucional, (33), 353–376. Recuperado de http://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4724065.pdf

3. Anastasiadis, S. (2006). Understanding corporate lobbying in its own terms. ICCSR, (42). Recuperado de http://www.nottimgham.ac.uk/business/ICCSR/research.php?action=download&id=38

4. Borchardt, K. (2011). El ABC de la Unión Europea. Luxemburgo: Oficina de Publicaciones de la UE.

5. Bouwen, P. (2002). Corporate Lobbying in the European Union: The Logic of Access. Journal of European Public Policy, 3(9), 365–390. Recuperado de http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/318/sps20015.pdf

6. Castillo, A. (2011). Lobby y comunicación. Sevilla y Zamora: Comunicación Social.

7. Calduch, R. (2011). Apuntes de la Unión Europea, en Marin, M. (Coord.) Aula Virtual de Relaciones Internacionales, Publicaciones Web. Recuperado de http://pendientedemigracion.ucm.es/info/sdrelint/apuntue.pdf. Comisión Europe. Recuperado de http://ec.europa.eu/civil_service/docs/directors_general/petite_en.pdf

8. Consejo Europeo (2015). El Consejo Europeo. El órgano estratégico de la Unión Europea, en Documentos y Publicaciones. Bruselas: Consejo Europeo. Recuperado de http://www.consilium.europa.eu/es/documents-publications/publications/2015/european-council-strategic-body-of-eu/

9. Correa, R. (2010). Comunicación: lobby y asuntos públicos. Cuaderno 33, 101–110. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/ccedce/n33/n33a09.pdf

10. El País (2014). Así actúan los lobbies en la UE, en Especial Europa. Recuperado de http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2014/04/29/actualidad/1398789625_477383.html

11. Europe Union (2010). The principle of cooperation between the institutions, en EUR Lex, European Union Law. Disponible en:

12. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1453376500757&uri=URISERV:l10125

13. Francés J. (2013). ¡Qué vienen los lobbies!, en Destino, Barcelona: La Vanguardia. Recuperado de www.lavanguardia.com/libros/20130429/54372866931/entrevista-juan-frances -lobbies.html

14. Gammelin, C. (2014). La vida en una Ley, en Diario El País de España (mayo 7 de 2014). Recuperado de http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2014/05/05/actualidad/1399292152_089478.html

15. García, J. (2008). Modelos de regulación del Lobby en el derecho comparado. Revista Chilena de Derecho, 35(1), 107-134. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.cl/pdf/rchilder/v35n1/art05.pdf

16. Guilló, M. y Mancebo-Aracil, J. (2017). Comunicación y participación online: la evolución de los procesos participativos en entornos virtuales. Communication Journal, (8), 413-434. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.21134/mhcj.v0i8.198

17. Hernández, J. (2013). Los lobbies financieros. Tentáculos del poder. Madrid: Clave Intelectual.

18. Hrebenar, R. y Thomas, C. (2008). Understanding interest groups, lobbying an d lobbysts in developing democracies. Jornal of Public Affairs, 8(1), 1–14. Recuperado de http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pa.v8:1/2/issuetoc

19. International Transparency (2015). Lobbying in Europe. Hidden Influence, Privileged Acces. París: IT y Co-funded by the Prevention of and Fight against Crime Programme of the European Union. Recuperado de http://www.transparencyinternational.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Lobbying_web.pdf

20. Join Transparency Register Secretariat (2012). Annual Report on the operations of the Transparency Register 2012. Bruselas Secretaries General of the European Parliament and the European Commission. Recuperado de http://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/staticPage/displayStaticPage.do?locale=es&reference=ANNUAL_REPORT.

21. Morata, F. (1995). Influir para decidir: la incidencia de los lobbies en la Unión Europea. Revista de Estudios Políticos, (90), 131. Recuperado de http://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/27357.pdf

22. Moriche, J. F. (2012). Puertas giratorias, Madrid: Attac.

23. Pearson, F. y Rochester, J. (2000). Relaciones Internacionales Situación global en el siglo XXI. Bogotá: Mc Graw-Hill.

24. Peña, A. (2011). Relaciones públicas y lobby. Gestión para la transparencia. Proyectos de Graduación. Recuperado de http://fido.palermo.edu/servicios_dyc/proyectograduacion/archivos/447.pdf

25. Peschard, J. (2001). La Cultura Política Democrática. México DF: Instituto Federal Electoral.

26. Registro de Trasparencia de la UE (2016). Estadísticas, en Portal de datos abiertos de la Unión Europea. Disponible en: http://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/homePage.do?redir=false HYPERLINK

27. Transparency International (2015). Lobbying in Europe, hidden influence, privileged Access. Recuperado de https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/lobbying_in_europe

28. Transparency International (2012). Tratado de la Unión Europea (TUE). Recuperado de http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012M/TXT&from=ES

29. Transparency International (2010). Tratado de Funcionamiento de la Unión Europea (TFUE). Recuperado de https://www.boe.es/doue/2010/083/Z00047-00199.pdf

30. Ure, M. (2018). Engagement estratégico y encuentro conversacional en los medios sociales. Revista De Comunicación, 17(1), 181-196. doi: https://doi.org/10.26441/RC17.1-2018-A10

31. Xifra, J. (2005). Los think tank y advocacy tank como actores de la comunicación política. Anàlisi, (32), 73–91. Recuperado de http://www.raco.cat/index.php/analisi/article/viewFile/15173/179893

AUTHOR

Ana Belén Oliver González: Doctor in Political Science and International Relations, Universidad Complutense. Thesis entitled: “Effects of persuasive communication of lobbies on the decisions of community institutions and member countries between 2005 and 2015”. Master’s degree in Political and Business Communication, Camilo José Cela University. Master thesis: “Influence of Lobby agencies in the European Union. Persuasive communication in the political institutions of Brussels during the period 1995 to 2010”. Degree in Protocol and Institutional Relations, Camilo José Cela University. Final Degree Project: “The protocol in the ceremony of investiture of Doctor Honoris Causa”.

anabeleo@ucm.es