doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.142.79-96

RESEARCH

THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL: A BABY IN THE SESSION OF CONSTITUTION OF THE GENERAL COURTS. THE TELEVISION TREATMENT OF THE CASE OF CAROLINA BESCANSA AND HER SON (JANUARY 13, 2016)

LO PERSONAL ES POLÍTICO: UN BEBÉ EN LA SESIÓN DE CONSTITUCIÓN DE LAS CORTES GENERALES. EL TRATAMIENTO TELEVISIVO DEL CASO DE CAROLINA BESCANSA Y SU HIJO (13 DE ENERO DE 2016)

O PESSOAL É POLÍTICO: UM BEBÊ NA SESSÃO DA CONSTITUIÇÃO DAS CORTES GERAIS. O TRATAMENTO TELEVISIVO DO CASO DE CAROLINA BESCANSA E SEU FILHO. (13 de janeiro de 2016)

Asunción Bernárdez Rodal1 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4081-0035

Marta Serrano Fuertes2

1Complutense University. Spain

2Degree in Audiovisual Communication. Spain

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the role of television news in the construction of the image of women in politics. Specifically, the issue is Carolina Bescansa, who came to the Congress with her baby on the day that the Spanish Parliament was constituted on January 13, 2016. The text analyzes how the news broke in the different generalist television channels in Spain: what representatives of the political parties intervened, how much time they were given the floor, and what was especially the argument used by the participants mainly to disqualify the decision of Bescansa. This case is an example not only of how women can be disqualified in politics for private matters, but also of how motherhood and caring are a subject for debate in our societies. An example that might drive towards a needed discussion over the re-thinking of what is accepted and acceptable in our society: both in the politician’s sceneario and in the critic’s grandtands. Because both spaces, complying with the democratic rule, are opening more and more to an increasing number of people, classes and backgrounds.

KEYWORDS: Television, Polítical Comunication, Women, Motherhood, Parlamentarism, Politic Spanish

RESUMEN

En este artículo se analiza el papel que tienen los informativos televisivos en la construcción de la imagen de las mujeres en política. En concreto se trata el tema de Carolina Bescansa que acudió al Congreso de los Diputados con su bebé el día en que se constituían las Cortes el 13 de enero de 2016. El texto realiza un análisis de cómo se dio la noticia en las distintas cadenas televisivas generalistas en España: qué representantes de los partidos políticos intervinieron, cuánto tiempo se les dio la palabra, y cuál fue sobre todo el argumentario utilizado por los participantes sobre todo para descalificar la decisión de Bescansa. Este caso es un ejemplo no sólo de cómo las mujeres pueden ser descalificadas en la vida política por cuestiones privadas, sino también de cómo la maternidad y los cuidados son un tema a debate en nuestras sociedades. Un ejemplo que puede llevar a una eventual y necesaria discusión sobre la necesidad de replantear algunos aspectos de lo considerado aceptado y aceptable en sociedad: tanto en la palestra de los políticos como en la grada de los críticos. Puesto que ambos espacios, en cumplimiento de la norma democrática, se están abriendo cada vez más a un número creciente de personas, clases y trasfondos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Televisión, Comunicación Política, Mujeres, Maternidad, Parlamentarismo, Política española

RESUME

Neste artigo se analisa o papel que tem os informativos televisivos na construção da imagem das mulheres na política. Em concreto se trata do tema de Carolina Bescansa que acudiu ao Congresso dos Deputados com seu bebê no dia 13 de janeiro de 2016, quando constituíam o Congresso. O texto realiza uma analises de como noticiaram nos distintos canais televisivos generalistas na Espanha: quais representantes dos partidos políticos interviram, quanto tempo tiveram a palavra, e qual foi o argumento utilizado pelos participantes, sobre tudo, para desqualificar a decisão de Bescansa. Este caso é um exemplo não só de como as mulheres podem ser desqualificadas na vida política por questões privadas, se não também de como a maternidade e os cuidados são um tema de debate em nossas sociedades.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Televisão, Comunicação política, Mulheres, Maternidade, Parlamentarismo, Política espanhola

Received: 15/010/2017

Accepted: 30/11/2017

Published: 15/03/2018

Correspondence: Asunción Bernárdez Rodal. asbernar@ucm.es

Marta Serrano Fuertes. martaserranofuertes@gmail.com

How to cite the article

Bernárdez Rodal, A., Serrano Fuertes, M. (2018). The personal is political: a baby in the session of constitution of the general courts. The television treatment of the case of Carolina Bescansa and her son. (January 13, 2016) [Lo personal es político: un bebé en la sesión de constitución de las cortes generales. El tratamiento televisivo del caso de Carolina Bescansa y su hijo. (13 de enero de 2016)].

Vivat Academia, Revista de comunicación, nº 142, 79-95

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.142.79-96

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1086

1. INTRODUCTION

Women are underrepresented in the political context. At present, only 12 are Premiers or Prime Ministers in all the countries of the world, and the elected female representatives in the Parliaments are now 20% in the world context. In Spain, at present, 138 seats are occupied by women out of the 350 that make up Congress. (Data provided in the Global Report of the gender gap prepared by The Word Economic Forum). But the scarce representation of women in parliaments and governments is not the only problem that affects women as political subjects in democratic societies.

Another important issue is that the public image of female politicians is often mistreated because they are women. Talking about their appearance, their age, their family or love relationships usually results in the devaluation of their public tasks, since they are alluded to in order to “drag” them into the field of private representation (Bernárdez, 2010; Padilla, 2017; D’Elia, 2013), and we already know that the private matter is always a devalued territory with respect to the public matter (Agra, 2006). Women are no longer “political subjects” to be “women”, marked by their sexual condition and the stereotyped ascription of gender. One of the consequences of this is that the power they hold always appears as a “delegated power” by some male body (Valcárcel, 1997; Cobo, 2004).

Finally, they are required to govern according to a series of topics and models of what women are socially considered to be, that is, “they must govern as women”. They are expected, for example, to be especially interested in social issues, to be empathetic, unaggressive and kind in their interventions. For women it is positive to maintain a “female rhetorical style” (Sheeler, K. H and Anderson, K. V. 2016) according to five precise features: 1.- To base political judgments on concrete lived experiences. 2.- To value the relational capacities of human beings and to govern in an inclusive manner. 3.- To value in public office the ability to “do things” and empower the others. 4.- To approach the political formation in a holistic way. 5.- To be interested in bringing to the public arena the questions of women. The female rhetorical style can not only be assumed by women, but also by men, and therefore they can appear in both sexes (Turska-Kawa & Olszanecka-Marmola, 2016). However, it is not clear that this rhetorical style favors women in politics (Menks and Domke, 2016), since it is easy for them to suffer from “double bind” (Bateson, 1985) in the sense that “whatever they do, their behavior is inadequate” (Bernárdez, 2010), and that it would consist of the following: a woman who behaves in an unfeminine way will be penalized because she is not entirely credible, but those who do not assume the feminine style are also so because they are not feminine. 1.1 Context of Spanish parliamentarism.

On January 13, 2016, the Parliament of the Eleventh Spanish Legislature were constituted, the shortest Spanish legislature in history, as a result of the elections held on December 20, 2015. For the first time in Spanish democracy, bipartisanship between the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) and the Popular Party (PP), was altered by the emergence of two young political forces: Citizens (actually it is a formation founded 10 years ago) and Podemos (which had “surprisingly” achieved an unexpected representation in the elections to the European Parliament in 2014). This Parliament, as defined by the media, is the “most fragmented in history.”

This parliament was not similar to its precedent, when the elections of 2011 had given the absolute majority to the PP with 186 seats as compared to 110 of the PSOE. The remaining 54 were distributed among 12 political forces. The third group with the greatest representation was Covengència i Unio with 16 seats. The PP returned to be the party with greatest representation, but lost 63 seats, 40 of which went to Citizens; the PSOE returned to be second force, but it lowered to 90 deputies, Podemos gained those 20 socialist seats as well as others to arrive at 69 and to become the third force of the country; the remaining 28 seats are divided among 6 parties. The 2015 elections not only ended that absolute majority of the PP, but created a game board the rules of which political parties had to learn.

The new Congress of Deputies was, also, for the first time, almost equal, since 138 women occupied a seat, which represented 39.4% of the total, bordering on equality standards (60/40). This distribution remained the same after the June elections. There had never been as many women in our political landscape as now; however, the power of the parties remains in male hands, since their main representatives are men, both for the “old” political parties as well as for the “new” policy. The strategy of Citizens was to present itself as a young party the objective of which was to eliminate the corruption of political institutions, while defending an ultra-liberal economic plan for Spain. Podemos, however, was really a new party formed from the popular mobilizations known as the 15-M, in which broad social sectors protested against the inability of the political class to respond to the economic and social crisis started in the year 2008. To Podemos, the political parties (which they call “the caste”) have a great responsibility in managing this crisis in favor of the financial groups, and to the detriment of the interests of the poorer classes.

What has happened in Spain in these and the following elections is not an isolated case. For example, in Ireland, Slovakia or Greece the elections also resulted in a parliament in which nobody had enough seats to be able to form a government. In the case of Greece, also a leftist as yet minority party (Syriza) and Alexis Tsipras won the victory, managed to reach the government, and tried to stand up to the Troika and its austerity measures.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this article is to analyze the treatment given by generalist televisions to the fact that a female politician, Carolina Bescansa, attended the investiture session of Congress with her son in her arms. On the one hand, we will analyze the way in which the image of a woman-mother, who is also the “quintessence” of femininity in a traditional context of representation, becomes part of the media scenography. Maternity models are a symbolic ground widely debated by the feminist theory in recent years, noting that, on the one hand, it is idealized, while the difficulties to be mothers have increased in our societies. For example, it is a fact that in Spain the birth rates have been reduced during the economic crisis, or that the average age for being mothers for the first time is around 32 years. These data tell us about the problems of women to have children and undertake care tasks.

Secondly, we will also analyze how the media have turned the tasks associated with motherhood into a spectacle, showing public figures with their multiple children without a critical discourse on the social class represented by these exemplary families ideally composed of five or more members. All this occurs while forging a greatly successful model in popular culture; the one of “mother surrendered” to motherhood. The success of this model is due to two groups of ideas that come together in a certain practice of motherhood. What has happened is that they have joined the discourses of cultural feminism that advocates the defense of feminine difference (Chodorow, 1984, Douglas, 2004), and some of the discourses of ecology, which add to the idea that the most satisfactory role for women is to be mothers, that this motherhood must be exercised in the most possible “natural” way. This includes, for example, preparing deliveries outside the conventional medical system or extending breastfeeding periods. Badinter (1991) has been criticizing for decades this model that turns motherhood into the “center of feminine destiny” (2011: 11), because it has, as a practical result, the exclusion, once again, of women of the social and productive system.

Our final objective is to analyze how, in this complex context of ideas and practices, what happens when a female politician with a great social and media presence, such as Carolina Bescansa, decides personally to appear in Congress with her son and then be submitted to the trial broadcast by the media and the other political groups. Her argument was that she wanted to make a protest action by taking her son to the session as a reminder of all the care that women do and that they do not have visibility in our social environment. Although it is outside our work, it must be said that her argument was not taken into account as an element of public debate. People of the right and left, feminists and non-feminists were outraged. She was dismissed as a frivolous person who instrumentalized her son and little was said about what she proposed as a topic of debate: the conciliation between private life and public work.

3. METHODOLOGY

How did the generalist chains treat “the vindication” of Bescansa? In order to find out, we recorded and analyzed all the television news (11 in total) at noon and night of La 1, La 2, Antena 3, Cuatro, laSexta and Telecinco. The method we have used has consisted in the analysis of the image and the analysis of the transcription of the texts that appeared in each one of them. We considered the time of each piece relevant, analyzing how many minutes and seconds each of the interventions occupied and the basic ideas around which the arguments of each of them revolved. We have classified the parties involved, whether they are men or women who are asked for a statement, and the main “topics” used in each of the arguments. We have kept Carolina Bescansa as the main figure, so as to analyze when or not a direct statement is asked, since whether or not they have the ability to express themselves is very important for those people mentioned in the media.

4. RESULTS

4.1. The visuality of power: the context of the entrance of Bescansa in the Hemicycle

As in all democratic countries (Padilla, 2015), the act of constitution of the new Parliament had a great media interest, especially because they had to sit on their political seats that came from the environment of Podemos. It was not only a question of incorporating “new faces” into politics, but also of facing the challenge of incorporating a series of people who proposed a “new way of doing politics” into the highest State institutions and that young, highly trained but in a certain way “delegitimized” (as many media showed) “ordinary people”, accessed political power, which seemed to belong “naturally” to the parties formed after the Transition. The most topical but also the most common ideas about the political context are produced and disseminated in the media. They not only represent what we are but also “what we want to be” and the constitution of Parliament is one of the most symbolic acts of the constitution of the current democracies. Proof of this is a professional fact: on this occasion, more than 500 journalists were accredited to attend the event, marking a historical record that was surpassed shortly after, on March 2 in the investiture session to which 800 journalists were accredited. All the morning television programs of the main radio and television stations in Spain had some direct connection with the Lower Chamber on the morning of January 13.

Parliament is the place where the political power that its parties occupy in the democratic game takes shape and is represented. The place where each party represents its ideological values through its male and female candidates. It is a place of hyper-representation, where everything acquires meaning: with whom they appear, at what time, whether or not they talk to the press, if they stop long or short at the official entrance, what clothes they wear, whether they smile or not at the cameras or companions ... on those occasions Congress becomes a “densely symbolic” place. For example, the way in which the four leaders dressed was in correspondence with the “symbolic” place occupied by each of the political forces. For that occasion, Mariano Rajoy, leader of the PP, chose a suit of classic cut, of dark color. His jacket buttoned, his shirt white and hits tie wide and blue. His image was that of a traditional and discreet man. Pedro Sánchez, of the PSOE, chose a more modern-cut suit. He appeared with his jacket unbuttoned, his tie thin and bright red. His appearance was elegant, but youthful and carefree. Rivera, of Citizens, appeared similarly dressed to Pedro Sánchez, but with a more discreet tie. And the dissident touch was that of Pablo Iglesias, who appeared as he usually does in television events: without a jacket or a suit, with a blue shirt not fully buttoned and without a tie. His appearance was that of a normal person, on a normal day. As he clarified later, that was precisely his intention, because “it is time for this House to be more like our country”, thus showing that the traditional political class is no longer exemplary.

On this occasion, the cameras looked for the “dissonant” elements with respect to the traditional model and were attentive to the “details” of the “scenography” of the new congressmen who gave vindicating touches to the event. Juantxo Lopez de Uralde, Rosa Martinez and Jorge Luis Ball (from the Ecological formation Equo integrated in Podemos) arrived by bicycle to Congress, wearing a green vest to protest against global warming. Pedro Arrojo wore a scarf with the colors of the rainbow. The deputies of Compromís approached to the sound of a paso doble and accompanied by a Valencian band.

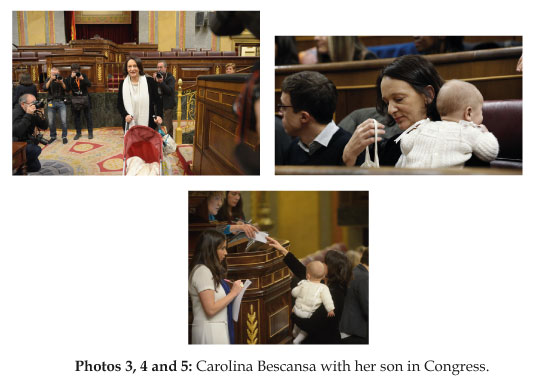

And in this context of exhibition of differences and vindications, Carolina Bescansa arrived with her baby. She also had it with her throughout the session, took it to vote, breast-fed it (as a curiosity, this image is very difficult to find on the Internet) and passed it to the arms of her colleagues on the bench. The media made Carolina Bescansa and her son the most important detail of the day.

The attention of the press on this fact suited the PP very well, because one of its deputies, Pedro Gómez de la Serna, involved in several cases of corruption, bribery, money laundering and criminal organization, also took over his office, despite his party had asked for his resignation. It was expected that this situation would attract great informative interest, however, no politician was questioned by journalists on this point.

4.2. The Television Treatment

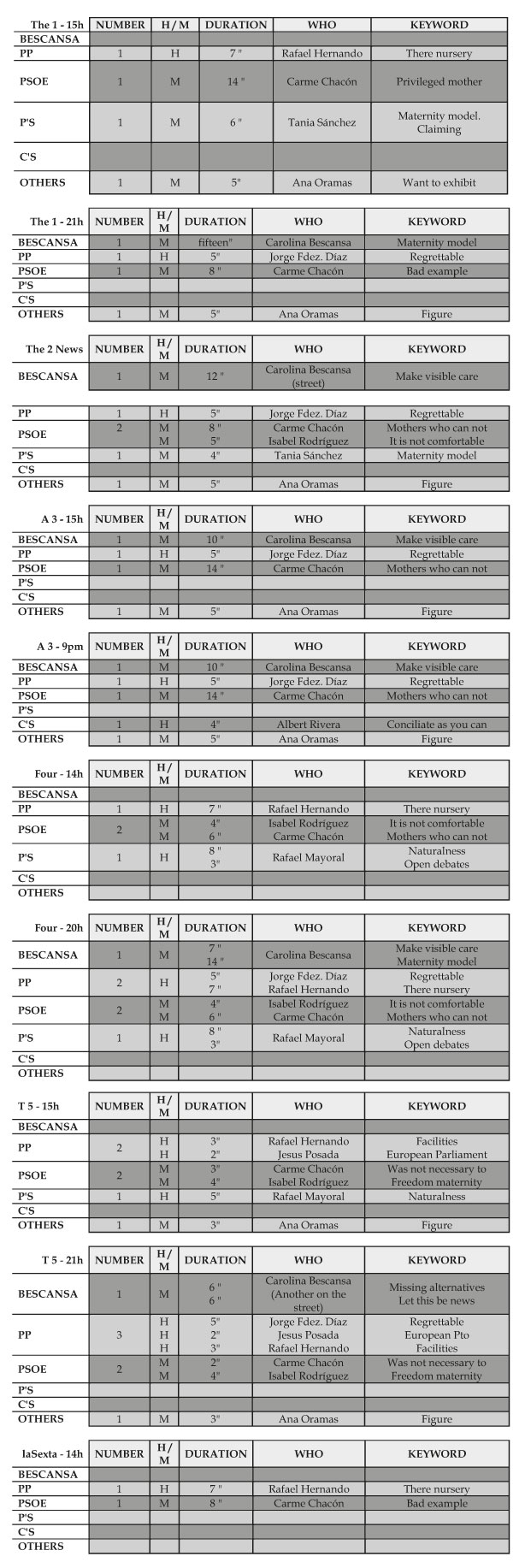

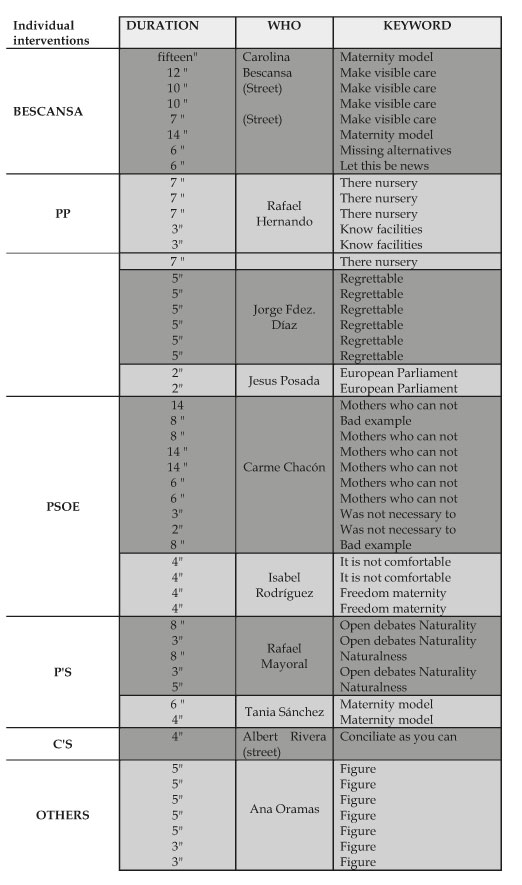

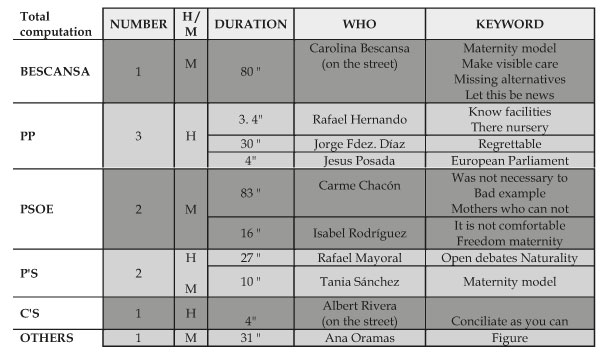

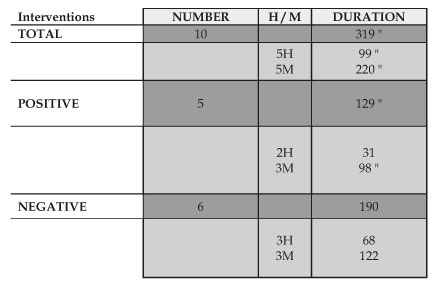

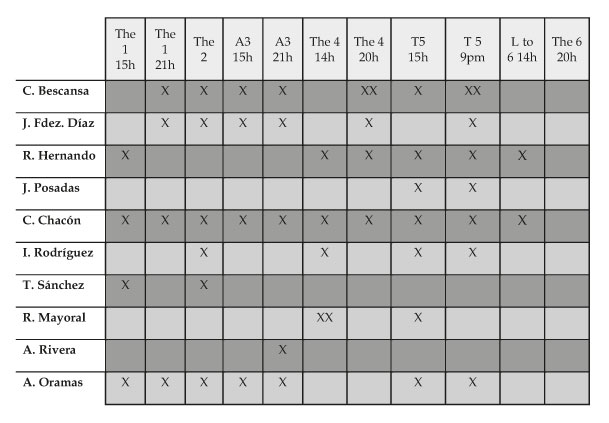

We have accurately told the times and the people that appear each of the generalist chains in the news of morning and night. The data we have obtained are the following:

In the first place, we have verified how many times the protagonist of the Carolina Bescansa news appears, in relation to the rest of the politicians and policies that gave evidence in each of the chains.

Total of all individual interventions

Total computation of interventions

Number of people involved and position they defend

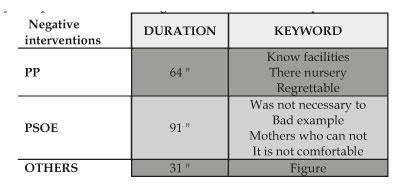

Statements by the parties involved against and duration of yours statements

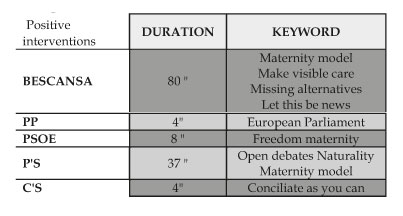

Interventions of the parties that are in favor and duration of their statements

Summary the presence or absence of political characters according to the channels.

5. DISCUSSION

In total, we have 9 people who have opined on the issue, in addition to Carolina Bescansa herself. They belong to five different parties: PP, PSOE, Podemos, Citizens and Canary Coalition (a party that supports the PP). There are five men and four women. The only voice that appears in all the news is that of Carme Chacón, of the PSOE, whom we hear saying 10 times that it is “a bad example”; Fernández Díaz, from the PP, describes the fact as “lamentable” 6 times and Ana Oramas of CC accuses Bescansa of notoriety desire 7 times.

Jorge Fernández Díaz (PP) said literally: “To me, instrumentalizing children for political purposes seems regrettable because there is a magnificent nursery.” This total was repeated 6 times throughout the day: in the two news programs of Antena 3 and Telecinco, in the second edition of La 1 and Cuatro, and in La 2 Noticias. Rafael Hernando (PP) also referred to the nursery “In this house there is a nursery to leave the children and it is good that they use the facilities and get to know them”, it was broadcasted in the two news programs of Cuatro and Telecinco and in the first edition of La 1 and the laSexta Noticias. While in the news of Telecinco, Jesus Posada (PP) played it down by saying: “It has already happened at the European Parliament”Ana Oramas (Canary Coalition), said literally: “A photo is not worth exposing a child and a minor.” This intervention was repeated in all news programs except Cuatro and La Sexta. Albert Rivera (Citizens) only appeared in Antena 3 news, saying “everyone reconciles their work and family life the best they can. My daughter is at school. “We have classified this statement as positive because it does not make a direct criticism, although we could also justify its classification as negative.

Carme Chacón (PSOE) was the person who most appeared in the media, she did it with these statements: “I feel bad because there are many working women in this country who cannot do this”; “...a bad example, because here we have made great efforts so that the female deputies who are not on maternity leave can breastfeed like I did with my son for three months, but nobody saw him here.” Her statements were broadcast by all chains, at noon and at night. In this argument, there is no doubt that the Socialist Party is the political group that has worked the most on feminist issues. In 2006, at the request of Chacón herself, the House set up the Congress nursery. It seems that they distanced themselves from Bescansa’s actions, not because they did not agree with demanding conciliation measures, but because of the fear that Podemos could capitalize on the historic efforts of the Socialist Party to maintain the feminist agenda of the country. To Isabel Rodríguez (PSOE) “Bringing it to the House is not suitable for the baby or for us” but she also defends “That each one does what he wants with his sons and daughters”. While the first edition of Cuatro and La 2 Noticas opted for the first cut, Telecinco did it for the second on its two newscasts. Is this another example of political bias?

Tania Sánchez (P’s) seems to influence not so much the liberation of women as the liberation of models of motherhood: “This is Carolina’s model and we must support the freedom of women to exercise motherhood as they wish. I think it’s a debate that we should overcome.” Her statements are collected only in the first edition of La 1 and La 2 Noticias. According to Rafa Mayoral (P’s) “Maybe there are debates that have to occur, right?” “I think you have to see it naturally, right? I wish it were something that ... in the European Parliament it is something usual, without problems” as the midday news from Cuatro and Telecinco said.

The characters and the times of these statements entail a bias in itself, because Carolina Bescansa herself appears very little, taking into account that she is the fundamental subject of the event. However, more than half of the news at noon do not offer her statements. In Telecinco, she appears only saying: “a little bit, a little bit,” as if she had nothing to say about it. In Antena3, she states: “I believe that what we have to do is make visible the people who in this country take care of others. There are millions of people who take care of children every day, take care of the elderly, take care of the sick ... “; at night in Cuatro: “I think it’s time to make visible what’s on the street inside the institutions. I think it’s time for this camera to look more like our country “; and on Telecinco: “if a mother has to raise a baby, she has to go everywhere with it, there is not much alternative”

At night, Telecinco and La 2 broadcast the following statement, which was taken at the door of the Congress: “It says a lot about this country that coming with a lactating baby to the Congress of Deputies becomes news, that means that we have to make visible much more the work of the women who raise our children.”

The gender bias is absent in the voice of the protagonist in half of the news, but also in the fact that she is asked for statements outside Congress, which seems to delegitimize her intervention by converting her into “ordinary people”. Although we could hear the message from Bescansa we did it with less forcefulness than the answers it received. And while she and her training partners direct their speech towards vindication: models of motherhood, freedom, conciliation, visualizing care ...; the rest is towards criticism: bad example, regrettable, figure, nursery ... The different news programs have not wanted to read that it was a protest act, no chain has accepted her argument and the nature of her performance has not been recognized.

It is a failure of action. Neither the media nor the parliamentarians accept the challenge. Among the politicians the sought debate is not generated, there is no talk of conciliation but partisan positions are maintained. While the media do not take advantage of the occasion to discuss conciliation or include a gender perspective, they limit it to a fight between parties.

There is a gender bias in Spanish news programs as this case demonstrates because, on the one hand, we can see how, once, gender issues are banalized by the press, they are treated anecdotally. It is not a matter of “all”, it is a matter of “these females”.

On the other hand, political conflicts quickly turn into media wars. It seemed that, with the emergence of emerging parties, politics had been filled with content, that it was closer to the people, but events of this kind take us back to the old scenario where politics is mere representation and the dramatic effect is sought..

The power that television continues to have in the era of social networks is paradoxical when it comes to building the image of political parties for citizens. Television condenses public life into images and gestures expressed in a few seconds, it is a “spectacular” medium. In current politics, both reporters and television sets have become fundamental pieces of public opinion. The irruption of a group like Podemos in the institutions has altered the way of speaking and representing the parties in this country. If the members of Podemos have exhibited a brand of “ordinary people”, some media have taken advantage of this vision to treat many of their representatives as susceptible to being devalued due to personal issues.

What happens is that politicians are treated as women have always been: commenting on the clothes they wear, the personal relationships they have with each other, the information about the family environments to which they belong, and so on. In the case of Carolina Bescansa, it is also the stereotype of the mother-woman who can be criticized for the worst maternal sin: to use her children to achieve spurious objectives, as in this case to get the attention of the cameras.

This action by Bescansa places the demands of a certain part of feminism in a contradiction. On the one hand, it is to return once again to the image of the woman associated with motherhood and care, selfless and willing, the woman returning to the private sphere; but on the other hand, it is to stage, as literally as possible, the phrase with which we title this chapter “the personal matter is political” because what can be more personal than motherhood and more political than Parliament?

REFERENCES

1. Agra MX (2006). Ciudadanía, feminismo y globalización. En AAVV, Lo público y lo privado en el contexto de la globalización. Sevilla: Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer. 67-96.

2. Badinter E (1991). ¿Existe el instinto maternal? Historia del amor maternal, siglos XVII al XX. Barcelona: Paidós.

3. Badinter E (2011). La mujer y la madre. Madrid: La Esfera de Libros.

4. Bateson G (1985). Pasos hacia una ecología de la mente, una aproximación revolucionaria a la autocomprensión del hombre. Buenos Aires: Lóale.

5. Bateson G (1977). Doble vínculo y esquizofrenia: el síndrome y sus factores patógenos interpersonales. Buenos Aires: Carlos Lohlé.

6. Bernárdez-Rodal A. (2010). Estrategias mediáticas de “despolitización” de las mujeres en la práctica política (o de cómo no acabar nunca con la división público/privado). CIC: Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación 15:197-218.

7. Chodorow N (1984). El ejercicio de la maternidad. Barcelona: Gedisa.

8. Cobo R (2004). Sexo, democracia y poder político. Feminismo/s 3:17-30.

9. D’Elia NS (2013). La mujer en la política: ¿igualdad o diferencia? Una invitación a la reflexión. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI 32:31-40.

10. Douglas S, Michaels M (2004) The mommy mith: the idealization of motherhood and how it has undetermined women. New York: Free Press.

11. Loke J, Bachmann I, Harp D (2017). Co-opting feminism: media discourses on political women and the definition of a (new) feminist identity. Media, Culture & Society 39(1):122-132.

12. Meenks L, Domke D (2016). When politics is a woman’s game: party and gender ownership in woman-versus-woman elections. Communication Research 43(7):895-921.

13. Padilla G (2015). La espectacularización del debate electoral: estudio del caso de Estados Unidos. Vivat Academia, Revista de Comunicación 132:162-181.

14. Padilla G (2017). La imagen y el estilo de la mujer política española como elementos básicos de su comunicación. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI 4262-64.

15. Sheeler KH, Anderson KV (2014). Gender, rhetoric, and international political systems: Angela Merkel’s rhetorical negotiation of proportional representation and party politics. Communication Quaterly 62(4):474-495.

16. Turska-Kawa A, Olszanecka-Marmola A (2016). A woman in politics or politics in a woman? Perception of the female leaders of polish political parties in the context of the 2015 parliamentary election. Communication Today 7(2):66-77.

17. Valcárcel A (1997). La política de las mujeres. Madrid: Cátedra.