10.15178/va.2018.144.37-49

RESEARCH

A DIDACTIC METHOD OF EMPOWERMENT FROM THE TV SERIES: «BLACK MIRROR»

UN MÉTODO DIDÁCTICO DE EMPODERAMIENTO A PARTIR DE LA SERIE DE TV: «BLACK MIRROR»

UM METODO DIDÁTICO DE EMPODERAMENTO A PARTIR DA SERIE DE TV: BLACK MIRROR

Víctor Cerdán-Martínez1

1Camilo José Cela University. Spain

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the Sci-Fi TV series “Black Mirror”, using linguistic and narrative morphologies as a starting point, with the objective of putting forward a teaching method that can be used with college students to encourage a reflective attitude. “Black Mirror” is original of “Netflix UK”; it has reached a huge audience and also harnessed very good reviews. Each chapter shows a near future where society lives submerged in a world made up of artificial images. The present research uses a qualitative method based on the narrative theories of J. Campbell, V. Propp and C. Vogler. Just as the fictional hero, the student is led into the journey that Campbell describes in his research “The hero of a thousand faces”: departure, initiation and return. The college student watches a “Black Mirror” episode (departure), performs a comparative analysis between the chapter and current society (initiation) and publishes it on social networks (return). This being specified, the author tests it with fifteen film school students from the Camilo José Cela University in Madrid. The intention being examining the validity of the method in a classroom and check its results. The final objective of this teaching method is to promote a reflexive attitude of college students and their empowerment regarding the emerging cybersociety.

KEY WORDS: Method; Televisión; Morphology; Student; Profesor; University; Fiction.

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza la serie de ciencia ficción «Black Mirror», desde la morfología lingüística y la morfología del relato, con el objetivo de proponer un método didáctico que sirva a profesores para impulsar una actitud reflexiva de los alumnos universitarios. «Black Mirror» es una serie, actualmente distribuida por «Netflix UK», que ha cosechado un éxito de crítica y espectadores. Cada episodio presenta un futuro próximo donde la sociedad vive sumergida en un mundo construido por imágenes artificiales. Esta investigación emplea una metodología cualitativa para confeccionar el método didáctico desde las teorías sobre la morfología del relato de J. Campbell, V. Propp y C. Vogler. Al igual que el héroe de ficción, el alumno es conducido por las mismas fases que enuncia Campbell en el «Héroe de las mil caras»: partida, iniciación y regreso. El alumno visiona un capítulo de la serie (partida), realiza una práctica (iniciación), y la publica en las redes sociales (regreso). El autor aplica el método didáctico propuesto a una muestra de quince alumnos de la Facultad de Cine de la Universidad Camilo José Cela de Madrid. La intención es examinar la validez del método en el aula universitaria y comprobar sus resultados. El resultado es un método didáctico que fomenta la actitud reflexiva y el empoderamiento de los alumnos con respecto a la emergente cibersociedad.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Método; Televisión; Morfología; Alumno; Profesor; Universidad; Ficción.

RESUME

Este artigo analisa a série de ciência e ficção Black Mirror desde a morfologia linguística e a morfologia do relato, com o objetivo de propor um método didático que sirva a professores para impulsar uma atitude reflexiva dos alunos universitários. Black Mirror é uma serie, atualmente distribuída por Netflix.uk, que a conseguido um êxito de crítica e espectadores. Cada episódio apresenta um futuro próximo onde a sociedade vive submergida em um mundo construído por imagens artificiais. Esta investigação emprega uma metodologia qualitativa para confeccionar o método didático desde as teorias sobre a morfologia do relato de J. Campbell, V. Propp e C. Vogler. Igual que o herói da ficção, o aluno é conduzido por as mesmas fases que anuncia Campbell em ¨Herói das mil caras¨: partida, iniciação e regresso. O aluno visiona um capítulo da série (partida), realiza uma pratica (iniciação), e a publica nas redes sociais (regresso). O autor aplica o método didático proposto a uma amostra de quinze alunos da Faculdade de Cinema da Universidade Camilo José Cela de Madri. A intenção é examinar a validez do método na aula universitária e comprovar seus resultados. O resultado é um método didático que fomenta a atitude reflexiva e o empoderamento dos alunos com respeito a emergente ciber sociedade.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Método; Televisão; Morfologia; Cidadania; Professor; Universidade; Ficção.

Received: 15/03/2018

Accepted: 30/06/2018

Correspondence: Víctor Cerdán Martínez. Camilo José Cela University. Spain

vcerdan@ucjc.edu

How to cite the article

Cerdán Martínez, V. (2018). A didactic method of empowerment from the TV series: “Black Mirror”. [Un método didáctico de empoderamiento a partir de la serie de tv: «Black Mirror]. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, nº 144, 37-49. doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.144.37-49 Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1078

1. INTRODUCTION

The words of Epictetus “initium doctrinae sit consideraratio nominis” (the principle of any exposition must be the consideration of names) are a guide to start any qualitative study that deals with communication. I consider it fundamental to situate some concepts (critical citizenry, empowerment and cybersociety), from their linguistic morphology, before starting this piece of research.

Ciudadanía (citizenry) comes from the Latin roots «civitas» (Roman citizenship), «anus» (belonging), «ia» (quality), and the suffix «ciudad (city)». Crítica (criticism) comes from the Greek «kritikos»: the one that separates the good from the bad. Empoderamiento (empowerment) comes from the Latin “in” (inward) “posse”, (power), and the suffix “miento (lie)” (instrument, medium or result). Social comes from Latin and means belonging to the community of people. Emergente (emergent) comes from the Latin roots “ex” (outward) “mergere” (submerge, sink) “nte” (the one who does the action). “Ciber” (cyber) comes from Greek and means, originally, rudder, and, later, space created by computer means. And finally, sociedad (society) comes from the Latin “societas” and means community of people.

From the above it follows that the critical citizen must have the quality to separate the good from the bad and to strengthen the bonds of union in a community of people that submerge themselves in a new space controlled by the computer media. The good thing, from its linguistic morphology, is what is efficient, what acts and achieves an effect, and the bad thing is just the opposite. That is to say, what is good, in relation to the critical citizenry of the emerging cybersociety, would be what is efficient to enhance the reflection and empowerment of a community of citizens.

Recent studies (Ortiz, 2000, Phillippi & Avendaño 2011, Cancelo & Gadea, 2013, Valenzano III, Wallace & Morreale, 2014, Dominguez, 2016) have demonstrated the relationships between empowerment, communication and new technologies. «Communication empowerment implies learning to relate the new social context with the available communication technologies so that it helps the subject to relate and relate collectively» (Phillippi & Avendaño, 2010, p. 68). Likewise, research (Kearney, Plax, Richmond & McCroskey, 1985, Carretero, 2006, Murphy & Simonds, 2007, Mazer, 2007, Clarembeaux, 2008, Warren, 2008) studies the importance of creating a critical citizenry around the contemporary technological media. “The objective continues to be to help young people to acquire a new type of media autonomy, a maturity that allows them to replace a type of consumption with reflective management” (Clarembeaux, 2008, p.98).

One of the central themes of the previous studies is the presence of the audiovisual stories in the current multiscreen (television, Internet and cinema). The series «Black Mirror», created by Charlie Brooker and currently distributed by «Netflix UK», has been a success concerning criticism and audience since its premiere. For example, in China, it is one of the five most popular Western series. In the academic field, recent studies (García-Noblejas, 2004, García Martínez, 2009, García Pousa, 2013, Gandasegui, 2014, Martínez & Cigüeña, 2014, Singh, 2014, Ungureanu, 2015) analyze “Black Mirror” from different approaches. According to Cigüeña and Martínez (2014, p.107), technology, as such, is neither a condemnation nor a promise of well-being; what it does is simply open a horizon of possibilities, and perhaps of new slavery, but also of participation, discussion and criticism.

Each chapter of “Black Mirror” tells a different story focused on a hypothetical future society with a background that encourages the viewer’s reflection. However, all the chapters deal with the same theme: life in the society of artificial images. The name imagen (image) comes from the Latin “imago”, (portrait, copy, imitation) and the artificial adjective, from “artificialis”, something creative made by man. The characters of «Black Mirror» belong to societies where artificial images have more influence than real ones (realidad (reality), from the Latin «realitis», that is, quality relative to real things). These characters live immersed in a virtuality produced by advanced technologies, and have forgotten the fact of living in real things.

On this subject, we highlight the following chapters of the series: “The national anthem” (the influence of videos on the Internet in politics), “The entire history of you” (the contact lenses that create a fictitious reality), «Nosedive» (living in a great social network), «San Junipero» (artificial immortality through new technologies), «Men against fire» (the space of war as a videogame). However, «Black Mirror» is not the first audiovisual story that deals with this subject.

The films “Total Recall” (Verhoeven, 1990), “Dark City” (Proyas, 1998) or “Matrix” (Wachowski, L., & Wachowski, L., 1999), already approach this idea. Although there are recent studies (Maffesoli, 2003, Illouz, 2009, Olson, 2009) that delve into the social imaginariness of virtuality, it is perhaps the allegory of the cave of Plato, collected in book VII of «The Republic», the oldest and most influential antecedent of all. The main innovation of this study, with respect to the cited authors, is to consider “Black Mirror” as a useful tool to develop a didactic method, which incites the reflective attitude and empowerment of university students.

Recent research (Chesebro, & McCroskey, 2001; Zhang, 2009; Rocca, 2010; William, 2012; Hendrix, & Wilson, 2014; Grilli, 2016, Andrew Ledbetter & Amber, 2016;) studies the use of movies, series, and television programs as teaching material in the classrooms. «A film can stimulate the senses of the spectator and, at the same time, contribute historical images and social themes. While movies are made to entertain, a textbook is made for another purpose “(Russell, 2012, p. 160). Likewise, the authors (Diez, 2006; Padilla, 2010; Requeijo, 2010; Valbuena, 2014) use audiovisual stories to teach students the keys to film scripts. According to Valbuena (2014, p. 192), in a drama, each act, each scene must also necessarily follow the one that it precedes and inevitably lead to those that follow. There must be, in every drama, a note of the inevitable.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this article is to create a didactic method that is useful to promote the empowerment of university students, from a critical and reflective attitude. The secondary objective is to apply this method to a sample of fifteen students from Camilo José Cela University, with the intention of studying the interaction of young people with the method in the classrooms.

3. METHODOLOGY

The author uses a qualitative methodology to propose a didactic method and, later, to examine it with a sample of fifteen students from Camilo José Cela University of Madrid. The theoretical preparation of the method starts from the morphology of the story by Campbell (1972), Propp (2006), and Vogler (2002). Propp (2006) it divides the structure of the story into 31 segments, which Diez (2006, p.160) adapts to the classical structure of the screenplay and regroups into three blocks: introduction (segments 1 to 11), node (segments 12 to 19) and outcome (segments 20 to 31).

Campbell (1972) divides the story into three major blocks called: departure, initiation and return. In turn, Vogler (2002) subdivides the three phases of Campbell (1972) into 12 parts: the ordinary world, the call of adventure, the rejection of the call, meeting with the mentor, crossing the first threshold, tests, allies and enemies, approach to the deepest cave, the odyssey, the reward, the way back, resurrection, and the return with the elixir. Just as fictional characters are subjected to the so-called journey of the hero and achieve a vital lesson at the end of the story, students can also go through a similar experience to achieve a greater reflective capacity at the end of the lesson. The idea of this analogy is not far-fetched, Vogler (2002, p.11) assures that the work of a writer, when faced with a new film script, follows the same path as the structure of the mythological heroes of Campbell (1972).

For the proposal of the didactic method, the author uses the phases of Campbell (1972), initiation, departure and return and the subdivision enunciated by Vogler (2002). And then, theory is contrasted with a case study, based on statements (Walker, 1983, Merriam, 1988, Yin, 2003) that are useful for the analysis of the collected data. Professor Emeterio Diez Puertas applies the proposed method to his subject, “Film script”, during a three and a half hour teaching unit at the Film School, on February 23, 2017. The purpose is for the professor to use the theoretical proposal through several practical exercises that will be collected in the next section (discussion).

4. DISCUSSION

The chapter that the author has selected is «Nosedive» of the third season of «Black Mirror» (2016). Lacie lives in a society of apparent happiness: smiles, good manners and obsession with the public image. Citizens wear the latest technology contact lenses with which they can see the comments and videos that other people post on their mobile phones, as well as take photos or record videos. Each person, depending on their influence in a large social network, has a number from 0 to 5 that the others can see at all times, and that is modified according to the votes obtained from the rest of the users. The more quality evaluations Lacie has, the greater her influence, and the better her social privileges. This causes the protagonist to behave with hypocrisy in their social relationships.

Lacie wants to buy a house in a luxury development, but for this she needs to increase her degree of influence from 4.2 to 4.5. Naomi, her popular friend since childhood, whom she has not seen for years, invites Lacie to give the bridesmaid’s speech at her wedding. Lacie will get to reach 4.5 and get to buy the house she wants, if the influential attendees vote her speech with five stars. However, the day before the wedding, Lacie’s trip by plane is canceled. From there, she loses her nerves and nothing goes well. She ends up desperate, drunk and, finally, arrested by the police. Once in jail, without the virtual contact lenses, or her cell phone, Lacie behaves with another inmate without fear of what he thinks of her. Both insult one another and, paradoxically, fall in love.

The departure of the hero (Campbell, 1972) is the moment in which an incident occurs to a hero and he has to leave his ordinary world. According to the regrouping carried out by Diez (2006, p.162) on the studies of the journey of the hero of Campbell (1972) and Vogler (2002), this phase is composed of: ordinary world, the call to adventure, the rejection of the call and meeting with the mentor. The ordinary world, cited by Vogler (2002, p.124), is the moment before the adventure, the hero’s everyday life before leaving.

In the proposed didactic method, this phase corresponds to the initial situation of the student before seeing the chapter of the series. The teacher asks the students about their expectations before they see «Black Mirror». A1 says he has not seen the series, but he has heard that it deals with the apocalypse of today’s society, A2 says they are very pessimistic episodes and do not correspond to reality. The call to adventure (Vogler, 2002, p.122) is the trigger that calls the hero to engage in a new adventure. In the didactic method, it is the moment in which the student views the chapter of «Black Mirror». To save time in the didactic unit, Professor Diez, entrusted the students with seeing «Nosedive» at home.

In the rejection of the call (Vogler, 2002, p.140), the hero refuses to start the adventure out of fear. The teacher performs a test on details of the chapter to verify that the students have seen it. 40% answer all the questions, 46.6% fail one of the answers. When asked why, A5 and A8 claim to have seen the chapter while looking at the cell phone or doing other things. Also, 13.3% do not pass the test and claim that they have not had time to see the chapter at home. According to the scheme of Campbell (1972) and Vogler (2002) these students rejected the call of adventure.

The meeting with the mentor is the strength of a guide, who helps the hero in his mission (Vogler, 2002, page 149). In the didactic method, it is the phase where the teacher uses the theoretical framework he has taught in previous lessons to apply it to the seen chapter of «Black Mirror». In this case, Diez uses cinematographic concepts (content map, premise, Janus table, philosophical idea, theme and leitmotiv) to the audiovisual content of the chapter. The objective is that students understand that, underlying each story, there are ideas and above all an ethical responsibility. After the teacher asks and discusses with the students, they arrive at a consensus conclusion about the philosophical idea of «Nosedive»: «The obsession to reach a high status in social networks through lying will make you lose everything, and at the same time you will learn to be yourself». Also, Diez asks what the premise of the chapter is and the students, after debating with one another, agree to sentence: “in the networks be yourself.”

As students manage to reduce the idea of the episode to a philosophical idea and a sentence, they cross the threshold of the hero. “Once the threshold is crossed, the hero moves in a dream landscape populated by curiously fluid and ambiguous forms, where he must go through a series of tests” (Campbell, 1972, 61). Campbell calls this second block initiation and Vogler (2002) regroups it in several levels: crossing the first threshold, tests, allies, enemies, approach to the deepest cave, the odyssey and the reward. In the proposed method, the student faces a series of tests, which, according to Vogler (2002, p.160), will make the hero learn rules and values of that special world and acquire a reward.

The teacher proposes to the students to carry out a practice inspired by the chapter. A comparative analysis, between «Nosedive», a newspaper article and the personal experience of the students. The teacher reads the case of Essena O’Neill, an Australian model, who left the social network “Instagram” because it reflected a false image of herself, which she herself had built. “Until the closing of her account, the model had 700,000 followers who admired her apparent perfect life” (López, 2015). First, she changed the descriptions of her photos, “I had more than 50 photos of myself taken to look pretty,” says O’Neill in a photograph in which she wears a white dress (Rodríguez, 2015). “They paid me 400 dollars to wear this dress,” she says in another photo (López, 2015). Then she creates on the Internet the initiative “Let’s change the game”, where she warns other young people about the risk of forming our image based on the approval of others. “I leave social networks to tell everyone: I felt miserable, I had “everything” and I felt miserable. In a video of her initiative, the model speaks to the camera: “Because when you let yourself be defined by numbers, you let yourself be defined by something that is not pure, that is not real and that is not love” (Rodríguez, 2015).

The next two stages, the approach to the deepest cave, and the odyssey (Vogler, 2002), the hero prepares to undertake the greatest challenge of his adventure and the most complicated test. The student writes the comparative analysis proposed by the teacher. A9 says that both girls live obsessed with reflecting an apparent perfect life in social networks. Lacie wants to reach 4.5 to get the house she wants, and O’Neill receives money for wearing certain dresses in the pictures of her profile. A6 ensures that Lacie and O’Neill suffer a moment of catharsis that makes them change their lives. In the fiction of «Black Mirror», Lacie is imprisoned and she shows herself as she is with another inmate. O’Neill, after leaving her social networks, appears in a video without worrying about her image, without wearing any makeup, to tell the whole truth of what was behind those images.

A4 emphasizes that the main difference between the story of Lacie and that of O’Neill is the institutionalization of social networks within the laws and politics of a State. In the fiction of «Black Mirror», the legislation of the State is related to social networks, in fact, each citizen is obliged to wear contact lenses and a mobile phone with which he can participate in the main social network. The Australian model O’Neill, unlike Lacie, can leave social networks and encourage others to do the same without legal consequences.

Regarding his personal experience, A7 assures that it does not matter how much or how little addicted you are to a social network, if you upload a photo and have few “I like it”, you will feel at least a little bad, instead, if your photo has many “I like it” a feeling of happiness invades you since you are being socially accepted.

A9 says he started using networks when being 13 years old, and at age 16 he joined “Twitter”, where he cared every day about the number of followers he had. The same student emphasizes that the key is to personally know the users that you follow, because then one becomes aware when someone creates an alter ego to show an apparent perfect life full of friends. Once all the students have finished the exercise, the teacher encourages them to extract a phrase from their writing that encourages reflection. This corresponds in the journey of the hero to Vogler’s reward phase (2002, p. 212).

The last block of the journey of the hero of Campbell (1972) is the return, that is, the conclusion of the story. In the allegory of the cave, Plato (1988, p.366) assures us that we must descend towards the common dwelling place of the others and accustom ourselves to contemplate the darkness of the cave; then, once we have become accustomed, things will look a thousand times better, since the one who has left knows the truth.

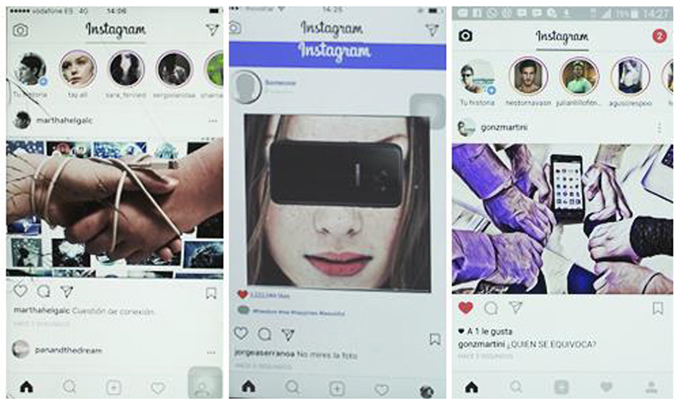

Vogler (2002) divides the return of Campbell (1972) into three stages: the way back, the resurrection and the return with the elixir. In the first, the hero tries to return home or goes deeper into the adventure to finish it off. Here, the teacher entrusts the students with a final test. The realization of a photograph with a text at the bottom, that incite the reflection of the viewer, and that is inspired by the plot of the chapter, by the philosophical idea, by the newspaper article and / or by his personal experience. The students, with the supervision of Diez, carry out the practice, inside or outside the classroom.

Source: VCM

Photo 1: Three mobile phones of students with photographs and texts posted on “Instagram”.

In the last phase, the return with the elixir (Vogler, 2002), the hero returns home with some kind of magical power that will make life easier and more prosperous for everyone. The teacher encourages students to upload the photograph and text to the social network “Instagram”. Finally, the students vote the best of all, and the teacher evaluates each student according to their participation, their practice and their final photograph. The three photographs (figure 1) best valued by the teacher had the following texts: “a matter of connection”, “do not look at the photo” and “who is wrong”.

The result of the study is a didactic method that has been effective for the students of Professor Diez to reflect on the current technological means and to share their experience in the social network “Instagram”. The following results also stand out: 100% of the students did the final practice, 86.6% of the students demonstrated having seen the chapter before arriving to class, while 13.3% did not see it. Professor Diez also did a test to check if the students had acquired the theoretical concepts, applied during the lesson. 86.6% passed the test, and 13.3% flunked it.

5. CONCLUSIONS - RESULTS

The main finding of this study is the proposal of a didactic method that serves teachers as a tool to educate through a television series: «Black Mirror». The data, from the analyzed case study, highlight the good participation of students in class and the high rate of passing in the test on theoretical concepts. It also highlights the creativity of the photographs and the texts posted on the “Instagram” network. The students, like the fiction hero, finished the lesson with a different assessment of the content of “Black Mirror” and social networks than what they had before they started.

This method, although it has served to promote a reflective attitude in the students of UCJC, does not guarantee that it can be useful in other classrooms of other countries and / or universities, as well as using other chapters of “Black Mirror”. However, the method, from a theoretical perspective, has the necessary characteristics so that future teachers can check it in their classrooms. That path is open for future studies and / or revisions.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

Although the impact of the final practice has not had a great social impact on “Instagram”, the very fact of encouraging students to share their academic work with other users, known and unknown, generates an attitude in favor of empowerment. Although the author has observed, in the case study, some figures of the journey of the hero (the mentor, the allies, the rejection of the call, the reward or the return with the elixir) in people or concrete actions, there are others that remained in a more subjective terrain. For example, who is the student’s enemy? Ignorance? Laziness? The teacher? Other students who wanted to go home before the lesson was over? This interpretation is also open.

In addition, the author concludes that the proposed didactic method can also be applied to other science fiction films. “Ex Machina” (the power of artificial intelligence), “The Dark Knight” (terrorism and cyber-vigilance), “Interstellar” (climate change), or “Her” (amorous relationships in the network), have arguments that question the emerging cybersociety. And it would even be applicable to other films of social genre, such as “Beautiful Youth”, that deal with the influence of the new technological ways of communication. This method, which was initially oriented only to university professors of communication science faculties, is more open than previously thought. It can also be useful for teachers of institutes or for family environments, where it is wanted to promote a critical attitude in the young people on the possible dangers of social networks and technological means, as well as of their positive interaction with them and with the rest of the citizens.

REFERENCES

1. Bordwell D (1996). La narración en el cine de ficción. Madrid: Paidós.

2. Brooker C (Creador), Bathurst O (Director) (2011). The national anthem (Episodio de serie de televisión) Black Mirror. Reino Unido. Channel 4.

3. Brooker C (Creador), Welsh B (Director), Armstrong J (Guionista) (2016). The entire history of you (Episodio de serie de televisión) Black Mirror. Reino Unido. Channel 4.

4. Brooker C (Creador), Wright J (Director), Schur M, Jones R (Guionistas) (2016). Nosedive (Episodio de serie de televisión) Black Mirror. Reino Unido. Netflix UK.

5. Brooker C (Creador), Harris O (Director) (2016). San Junipero [Episodio de serie de televisión] Black Mirror. Reino Unido. Netflix UK.

6. Brooker C (Creador), Verbruggen J (Director) (2016). Men against fire (Episodio de serie de televisión) Black Mirror. Reino Unido. Netflix UK.

7. Campbell J (1972). El héroe de las mil caras. México: Fondo de cultura económica México.

8. Cancelo M, Gadea G (2013). Empoderamiento de las redes sociales en las crisis institucionales. Revista de comunicación Vivat Academia, 124, 21-33.

9. Carretero AE (2006). La persistencia del mito y de lo imaginario en la cultura contemporánea. Política y Sociedad, 43(2):107-126.

10. Cigüeña J, Martínez J (2014). El imaginario social de la democracia en «Black Mirror». Revista Latina de Sociología, 4(1):90-109. Doi: 10.17979/relaso.2014.4.1.1223

11. Domínguez A (2016). Participación y empoderamiento en proyectos de comunicación para el desarrollo (2016). Revista española de desarrollo y cooperación, 38, 27-36. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/aTCsMI

12. Clarembeaux M (2008). La educación crítica de los jóvenes en TV en el centro de Europa. Comunicar, 31(XVI):91-98. Doi: 10.3916/c31-2008-01-011

13. Chesebro JL, McCroskey JC (2001). The relationship of teacher clarity and immediacy with student state receiver apprehension, affect, and cognitive learning. Communication Education, 50, 59–68. Doi: 10.1080/03634520109379232

14. Díaz V (2014). Black Mirror: el reflejo oscuro de la sociedad de la información. Teknokultura, 11(3):583-606. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/xwLvA9

15. Diez E (2006). Narrativa fílmica. Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos.

16. García AN (2009). El espejo roto: la metaficción en las series anglosajonas. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 64, 654-667. http://10.4185/RLCS-64-2009-850-654-667

17. García L (2013). El espejo televisivo de Claude. Estética, ciencia y ficción en «Black Mirror». Secuencias: Revista de historia del cine, 38, 47-64. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/IiwN7T

18. García-Noblejas JJ (2004). Identidad personal y mundos cinematográficos distópicos. Comunicación y Sociedad, 17(2):73-87. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/QGHsRC

19. Garland A (Director) (2015). Ex Machina. [Película]. Reino Unido. Universal Studios.

20. Grilli J (2016). Cine de ciencia ficción y enseñanza de las ciencias. Dos escuelas paralelas que deben encontrarse en las aulas. Revista Eureka, 13, 137-148. Recuperado de http://hdl.handle.net/10498/18019

21. Hendrix KG, Wilson C (2014). Virtual Invisibility: Race and Communication Education. Communication Education, 63(4):405-428. Doi: 10.1080/03634523.2014.934852

22. Illouz E (2009). Emotions, Imagination and Consumption. A new research agenda. Journal of Consumer Culture, 9(3):377-413. Doi: 10.1177/1469540509342053

23. Jonze S (2013). Her (Película). Estados Unidos. Warner Bros & Koch Entertainment.

24. Kearney P, Plax TG, Richmond VP, McCroskey JC (1985). Power in the classroom III: Teacher communication techniques and messages. Communication Education, 34, 19–28. Doi: 10.1080/03634528509378579

25. Ledbetter AM, Finn AN (2016). Why do students use

mobile technology for social purposes during Class? Modeling teacher credibility, learner empowerment, and online communication attitude as predictors. Communication Education, 65(1):1-23. Doi: 10.1080/03634523.2015.1064145

26. López M (4 de noviembre de 2015). La estrella de Instagram revela sus engaños. El País. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/FSd4lz

27. Maffesoli M (2003). El imaginario social de la democracia de «Black Mirror». Revista Anthropos. Huellas del conocimiento, 198, 149-153. Doi: 10.17979/relaso.2014.4.1.1223

28. Marlow S (10 de julio de 2016). ‘«Black Mirror»’ Creator Charlie Brooker on China’s ‘Social Credit’ System and the Rise of Trump. The Daily Beast. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/BVHkaP

29. Martínez J, Cigüela J (2014). Pensamiento pop en «Black Mirror». El monstruo y su linchamiento. Doxa Comunicación: revista interdisciplinar de estudios de comunicación y ciencias sociales, 19, 85-107. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/kcYXCY

30. Mazer J, Murphy R, Simonds C (2007). I’ll see you on «Facebook»: The effects of computer- mediated teacher self-disclosure on student motivation, affective learning, and classroom climate. Communication Education, 56, 1–17. Doi: 10.1080/03634520601009710

31. Merriam S (1988). Case Study research in education. A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

32. Nolan C (Director) (2008). The Dark Knight [Película]. Estados Unidos: Warner Bros & FilmFlex.

33. Nolan C (Director) (2014). Interstellar [Película]. Estados Unidos: Paramount Pictures.

34. Olson R (2009). Meta-televisión: Popular Postmodernism. Critical Studies in Mass Communications, 4, 284-300. Doi: 10.1080/15295038709360136

35. Ortiz AM (2000). Expressing cultural identity in the learning community: Opportunities and challenges. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 82, 67–79. Doi: 10.1002/tl.8207

36. Padilla G (2010). Las series de televisión sobre médicos (1990-2010): su éxito desde el Análisis Transaccional y la Ética (I). Revista de Análisis Transaccional y Psicología Humanista, 63, 244-260. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/CigNHA

37. Phillippi A, Avendaño C (2011). Empoderamiento comunicacional: competencias narrativas de los sujetos. Comunicar, 36(XVIII):61-68. Doi: 10.3916/C36-2011-02-06

38. Platón (1988). República. Madrid. Editorial Gredos.

39. Propp V (2006). Morfología del cuento. Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos.

40. Proyas A (Director) (1998) Dark City [Película]. Estados Unidos: New Line Cinema.

41. Requeijo P (2010). Mad Men desde el Análisis Transaccional: Las claves de sus protagonistas. Revista de Análisis Transaccional y Psicología Humanista, 63(XVIII):261-279. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/Q9DiYC

42. Rodríguez S (4 de noviembre de 2015). Essena O’Neill, la modelo que dejó las redes sociales porque ‘no son la vida real’. El Mundo. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/h8mgRs

43. Rocca K (2010). Student participation in the classroom: An extended multidisciplinary literature review. Communication Education, 59, 185–213. Doi: 10.1080/03634520903505936

44.Rosales J (Director) (2014). Hermosa juventud (Película). España. Wanda Visión.

45. Russell WB (2012). The art of teach social studies with film. The clearing house: a Journal of educational strategies, issues and Ideas, 82, 157-164. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/cBiqoX

46. Singh G (2014). Recognition and the image Mastery as Themes in «Black Mirror». International Journal of Jungian Studies, 6(2):120-132. Doi: 10.1080/19409052.2014.905968

47. Ungureanu C (2015). Aestheticization of politics and ambivalence of selfsacrifice in Charlie Brooker’s The National Anthem. Journal of European Studies, 45(1):21-30. Doi: 10.1177/0047244114553767

48. Valbuena F (2014). Tramas, guiones y las cinco partes de una obra. Revista de Análisis Transaccional y Psicología Humanista, 65, 181-205. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/MqNk5u

49. Valenzano-III J, Wallace S, Morreale S (2014). Consistency and change: The (R) Evolution of the basic communication course. Communication Education, 63, 355-365. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/TdSg6r

50.Verhoeven P (Director) (1990). Total Recall [Película]. Estados Unidos: Columbia Pictures.

51. Vogler C (2002). El viaje del escritor. Madrid: Ma Non Troppo.

52. Wachowski L, Wachowski L (Directores) (1999). Matrix [Película]. Estados Unidos. Warner Bros & Roadshow Entertainment.

53. Walker R (1983). La realización de estudios de casos en educación. Ética, teoría y procedimientos. Madrid: Narcea.

54. Warren JT (2008). Performing difference: Repetition in context. Journal of International & Intercultural Communication, 1, 290–308. Doi: 10.1080/17513050802344654

55. Yin R (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. California: SAGE.

56. Zamora A (25 de abril de 2012). Charlie Brooker: El tema de ‘Black Mirror’ es cómo la tecnología destroza la vida. Cien Megas. Recuperado de http://goo.gl/Knjz3L

57. Zhang Q (2009). Perceived teacher credibility and student learning: Development of a multicultural model. Western Journal of Communication, 73, 326–347. Doi: 10.1080/10570310903082073

AUTHOR

Víctor Cerdán

Víctor Cerdán is a doctor of journalism from the Complutense University of Madrid. Currently, he is a member of the GISDA research group at Camilo José Cela University, where he has taught the subjects: «Theory of Communication» and «Making Fiction». He has been a professor at the workshop of new filmmakers of ECAM (Madrid Film School) and at Tracor Institute (San Pablo CEU University). In addition to his academic experience as a researcher and professor, he works in films and television. He is director of the series of documentaries, “Invisible Heroes”, broadcast on La 2 (RTVE). and of the short films «Radio Atacama» and «The Evil» selected and awarded at International Festivals (Malaga, Berlin, Mexico, Hamburg, Paris, Vila Do Conde, Seoul, Madrid, Tehran, etc).

http://0000-0002-0069-5063