10.15178/va.2018.143.01-23

RESEARCH

MARKETING 2.0 APPLIED TO THE TOURISM SECTOR: THE COMMERCIAL FUNCTION OF THE WEBSITES OF DESTINATION MARKETING ORGANIZATIONS

MARKETING 2.0 APLICADO AL SECTOR TURÍSTICO: LA FUNCIÓN COMERCIAL DE LOS SITIOS WEBS DE LAS ORGANIZACIONES DE MARKETING DE DESTINOS

MARKETING 2.0 APLICADO AO SETOR TURISTICO: A FUNÇÃO COMERCIAL DAS PÁGINAS WEBS DAS ORGANIZAÇÕES DE MARKETING DE DESTINOS

Alba-María Martínez-Sala1

1Department of Communication and Social Psychology, University of Alicante. Spain

ABSTRACT

This article evaluates the development of the commercial role of the official tourist websites of the Spanish destinations which offer focuses on the sun and beach product, as this is the main attraction for tourists in Spain and because the websites are essential marketing tools for tourism products and services. The methodology is based on the literature review about marketing and Internet in the tourism sector, and on the commercial role of websites in general and, in particular, of the official tourist websites. An exploratory study of the official Spanish tourist websites of destinations focusing on the sun and beach product is undertaken by means of the analysis of content of variables concerning their commercial function, and of their evolution since the arrival of the model 2.0. This article starts with the hypothesis that official tourist websites have evolved into more commercial models. The results achieved by the study verify this hypothesis, but reveal failure to take advantage of the benefits that marketing 2.0 can offer. Furthermore, this study suggests a series of measures that destination marketing organizations should adopt to remedy these shortcomings and optimize the commercial function of their websites.

KEY WORDS: Tourism; website 2.0; Internet; marketing 2.0; commercialization; Official tourist website; e-commerce

RESUMEN

El artículo estudia evolutivamente la función comercial de las webs turísticas oficiales de los destinos españoles cuya oferta se centra en el producto sol y playa, por ser este el motor principal del turismo en España, y por ser la web una herramienta indispensable en la comercialización de sus productos y servicios. La metodología se basa en una revisión bibliográfica sobre marketing e Internet en el sector turístico y sobre la función comercial de los sitios webs en general y de los turísticos oficiales en particular. Se desarrolla un estudio exploratorio de las webs turísticas oficiales españolas de los destinos cuya oferta se centra en el producto sol y playa mediante un análisis de contenido de variables relativas a su función comercial, así como de su evolución desde la llegada del modelo 2.0. Se parte de la hipótesis de que las webs turísticas oficiales han evolucionado hacia modelos más comerciales y se alcanzan unos resultados que verifican dicha hipótesis, pero evidencian una falta de aprovechamiento de las ventajas del marketing 2.0. Por otra parte, el estudio sugiere una serie de medidas que las organizaciones de marketing de destino deben adoptar con el fin de remediar estas deficiencias y optimizar la función comercial de sus sitios webs.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Turismo; web 2.0; Internet; marketing 2.0; comercialización; web turística oficial; e-commerce

RESUME

O artigo estuda evolutivamente a função comercial das webs turísticas oficiais dos destinos espanhóis cuja oferta centra-se nos produtos sol e praia, por ser o motor principal do turismo na Espanha e por ser a WEB uma ferramenta indispensável na comercialização de seus produtos e serviços. A metodologia baseia-se em uma revisão bibliográfica sobre marketing e internet no setor turístico e sobre a função comercial das páginas webs em geral e dos destinos turísticos oficias em particular. Desenvolve um estudo exploratório das webs turísticas oficias espanholas dos destinos cuja oferta centra-se no produto sol e praia mediante uma analises de conteúdos variáveis relativas a função comercial. Assim como de sua evolução desde a chegada do modelo 2.0. Partindo da hipótese de que as Webs turísticas oficiais evolucionaram a modelos mais comerciais alcançando resultados que verificam essa hipótese. Mas evidenciam uma falta de aproveitamento das vantagens do marketing 2.0. Por outra parte, o estudo sugere uma série de medidas que as organizações de marketing de destino devem adotar com a finalidade de remediar estas deficiências e otimizar a função comercial de suas páginas webs.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Turismo; Web 2.0; Internet; Marketing 2.0; Comercialização; Web turística oficial; e-commerce

Received: 24/09/2017

Accepted: 30/11/2017

Correspondence: Alba María Martínez Sala

albamaria.martinez@ua.es

How to cite this article

Martínez Sola, A. M. (2018). Marketing 2.0 applied to the tourism sector: the commercial function of the websites of destination marketing organizations. [Marketing 2.0 aplicado al sector turístico: la función comercial de los sitios webs de las organizaciones de marketing de destinos]

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 143, 01-23

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.143.01-23

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1065

1. INTRODUCTION

The present and future forecasts make tourism a solid sector on which to sustain the socioeconomic development of a territory (General Subdirectorate of Tourism Knowledge and Studies, Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism and Tourism Institute of Spain, 2016). The opportunities offered by this sector have led to strong competitiveness, increasing the development of marketing actions aimed at achieving an advantageous position in the market. These actions are undertaken both by Public Administrations as by private companies (Mediano Serrano, 2002). Simultaneously, the development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has resulted in a new way of planning and consuming tourism products and services (Buhalis and Law, 2008) boosting the growth of e-commerce in the sector (Domínguez Vila and Araújo Vila, 2014).

In this context, there is a growing concern about the application of marketing and online marketing focused on the consumer (Cortés, 2009), as well as management, also, with a clear orientation to the client (Bigné, 1996) that, in the field of public administration, is manifested in neo-business trends (Campillo Alhama, 2013).

This paper analyzes the degree of implementation of online marketing in sun and sand tourism in relation to the commercial function of the official tourist websites. It is intended to establish a set of premises that serve to develop websites that effectively fulfill their commercial function.

2. MARKETING AND INTERNET IN THE TOURISM SECTOR

The importance of the Internet in today’s society is evident in the figures relative to its penetration. The study by the Association for Media Research (2016) states that the Spanish Internet users amount to 17.9 millions. The number of users is also growing among tourists (Google Travel Spain, Institute of Tourism Studies, Exceltur, Allianz, State Secretariat of Tourism of the Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism of the Government of Spain and AddedValue, 2013). These data are only a glimpse of the changes that are taking place in the forms of consumption of information and products and services. Specifically in the tourism sector, a new profile known as tourist 2.0 has emerged (Suau Jiménez, 2012) who is not only informed of the tourist offer but also uses it through the Web (Domínguez Vila and Araújo Vila, 2014). The Internet has meant important changes in the planning of the trip and in the reservations of tourist products and services (Duncan Ortega, 2009). Among them, the replacement of traditional intermediaries, travel agencies or tour operators, with websites (Lanquar, 2001). Hence the emphasis of companies and tourism agencies in investing a greater budget in technology and innovation (Domínguez Vila and Araújo Vila, 2014) and the necessary rethinking of the marketing strategies of tourism products and services by placing value on online marketing.

During the current generation of online marketing: marketing 2.0, there have been important changes (Martínez González, 2011) that affect tourist websites. These have become more interactive and better technically (Polo, 2009) to achieve a more satisfying user experience and greater integration of the user in the system. In addition, they implement online sales tools (Martínez González, 2011) to meet the expectations of users and those responsible for the websites. There are also changes in the field of tourism promoters with the massive entry into the Internet of public institutions that, exercising their socio-economic responsibility and aware of the strategic importance of the tourism sector, are commercialized by adopting processes and tools from the private sector of the economy (Martínez González, 2011).

This way, in the era of marketing 2.0, the main marketing variables (Luque and Castañeda, 2007) began to be integrated into the tourist website, among which and in relationship to the commercial function is e-product, tourism products and services are presented as in a store, with their benefits and attributes, and e-sale, the tourist pages and sites incorporate mechanisms that encourage sales and facilitate immediate payment (Sánchez, 2002).

Despite the prominence of the commercial function and the boom of online commerce, referred to in the following section, in the tourism sector, the Internet is basically used as a reference channel (Google Travel Spain et al., 2013). Faced with this reality, destination marketing organizations (OMDs) should provide tools for selection, booking and / or online purchase of tourism products and services (World Tourism Organization, 1999, 2001) to meet the expectations of tourists 2.0 (Suau Jiménez 2012) and the premises of marketing 2.0. Especially on their websites as they are the main channel of distribution and marketing of the tourist destination (Fernández-Cavia Diaz-Luque, Huertas, Rovira, Pedraza-Jiménez, Sicily, Gomez and Miguez, 2013; Fernández Cavia, Vinyals Mirabent and López Pérez, 2013 a; Hallet and Kaplan-Weinger, 2010; Lee and Gretzel, 2012; Luna-Nevarez and Hyman, 2012; Palmer , 2005 ).

Online marketing of tourism products and services is key to the economic development of destinations and a service demanded by the tourist 2.0. The limited role still played by the Internet in the phase of purchase and reservation of the tourism process raises questions about the possible causes. The first and most obvious focuses on the possibilities websites offer to carry out this process. Their study requires analyzing the commercial function of official tourist websites for its key role, and therefore the implementation of some of the essential variables of marketing 2.0: e-product and e-sale.

3. THE WEB AS A COMMERCIALIZATION CHANNEL

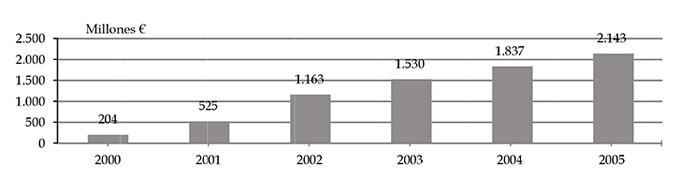

From the birth of the web to 2005 (1), we lived in the era of the web 1.0 model, the main interests and objectives of which were: content, profitability, mass public and commerce (Nafría, 2008). The Amazon digital store, the travel websites Travelocity or Expedia, among many others, were the maximum exponent of what the Internet allowed. In the field of electronic commerce, in Spain, the web 1.0 model was an unprecedented success, as shown by its business figures (Graph 1).

(1) Aunque el término web 2.0 fue acuñado en el año 2004 por el grupo editorial O´Reilly Media y Media Live International, fue perfilado un año más tarde por Tim O´Reilly (O´Reilly, 2005) por lo que se fija en el año 2005 el inicio de la era 2.0.

Source: National Institute of Statistics (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016).

Graph 1. Evolution of B2C e-commerce in Spain (2000-2005). Source: National Observatory of Telecommunications and the Information Society (2007)

As a result of model 1.0, webs began to appear in which the user abandoned his traditional passive role in favor of a more active one to the point of becoming at the same time the destination and origin of the communication. The web acquired an eminently social function. The phenomenon was so massive and so fast that it soon became a new web model: model 2.0 (O’Reilly, 2005).

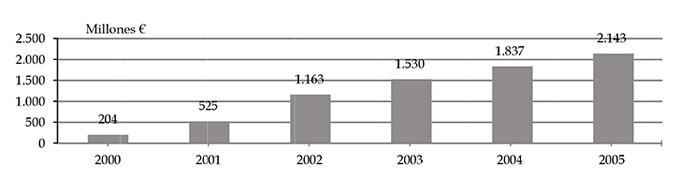

Web 2.0 represents the current phase and is characterized by the prominence given to the social (Lacalle, 2011). The question is whether this social character contravenes the commercial function of the previous web model. Although the web 2.0 model enhances interaction with and among individuals, it also promotes that the Web simplifies business processes of organizations and everyday consumers. Therefore, from the point of view of the business function, model 2.0 is not far from model 1.0. Proof of this are the figures resulting from online commercial transactions since the arrival of the new model (Graph 2).

Source: National Institute of Statistics (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016).

Graph 2: Evolution of the volume of electronic commerce (2005-2015).

Nowadays the Internet is still used to sell, what changes is the way to sell and who sells, both in the sense of advising and informing, because now users are the main prescribers of the products and services (Caro, Luque and Zayas, 2015); as in selling, transactions between individuals [C2P] are becoming more common (Cetelem, 2015).

4. THE COMMERCIAL FUNCTION OF OFFICIAL TOURIST WEBSITES

Websites are key to the development of the tourism sector as they constitute the main form of consumption of tourist information (Law, Qi and Buhalis, 2010, Luna-Nevarez and Hyman, 2012, Park and Gretzel, 2007). Therefore, destinations must have an official website, unique for the tourism brand, which exercises an informative and persuasive function that favors commercialization (Fernández Cavia et al., 2013a). In this sense, websites should facilitate the accomplishment of successive stages in the purchase process (Rastrollo Horrillo and Alarcón Urbistondo, 1999), and in the planning of the tourist trip and stay (Díaz-Luque, Guevara Plaza and Antón Clavé, 2006).

Regarding Public Administrations, the scope of this piece of research, they act as regulatory agents and promoters of the tourism sector through the Network (López Sánchez, Chica Ruiz, Arcila Garrido, Azzariohi and Soto Benito, 2010). They must adopt the role of intermediary in the company-company processes [B2B] and C2P, and provide tools and online marketing channels. However, the studies carried out to date point out that for OMDs to play this role does not seem to be a priority (Díaz-Luque, Guevara Plaza, Caro Herrero, 2004, Díaz-Luque et al., 2006, Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín, 2013, Fernández Cavia et al., 2013, Huertas Roig and Fernández Cavia, 2006). The human and technical cost of these channels might be he reason for their scarce implementation but, as indicated by Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín (2013), the final consumer is indifferent to who provides the final service, which opens a wide fan of possibilities for the OMDs to encourage commercialization without direct intermediation. The aforementioned authors distinguish between webs that offer their own purchase and / or reservation systems and those that link with others. Within them, they also observe several possibilities: reservation systems managed by professional destination groups or by private tourist intermediaries. Both are valued positively (Diaz-Jimenez Luque and Marin, 2013;. Diaz Luque et al, 2006) although it should be noted that, in the last case, destinations compete directly with products and services from other destinations. Another aspect to consider when implementing business applications on the web is usability, a key determinant of user satisfaction (International Organization for Standardization, 1998; Park and Gretzel, 2007; Yeung and Law, 2006). It is advised in this sense that applications and tools should be displayed on the same website, even in the same window, avoiding redirecting users to other websites as this causes confusion and possible abandonment (Nielsen, 1997).

Payment modalities must also be contemplated as they determine the completion of the purchase process. Although Paypal leads the ranking of payment methods, the debit card is another highly valued option (Cetelem, 2015, Institute Advertising Bureau Spain [IAB Spain] and Viko we are, 2015). This entails the need to offer several payment alternatives to meet the needs of potential and real tourists. And finally, security should be noted as another of the determining criteria of e-commerce. This has been indicated as the most valued aspect in relation to payment methods by 76% of consumers (Cetelem, 2015).

With regard to tourism products and services that are the object of this commercial function, the following categories are considered: accommodation, transportation, catering and complementary activities of a sport, cultural, leisure, etc. nature. They have been analyzed, individually or jointly, by authors such as Díaz-Luque et al. (2004), Díaz -Luque et al. (2006), Huertas Roig and Fernández Cavia (2006), Fernández Cavia et al. (2013a), Fernández-Cavia et al. (2013) and Fernández Cavia, Vinyals Mirabent and López Pérez (2013b) in relation to the ability to online disseminate and market tourism products and services as a determinant of the quality of an official tourist website that should therefore be analyzed.

5. OBJECTIVES

This piece of research is based on the hypothesis that OMDs have remodeled official tourist websites, based on marketing 2.0, incorporating the variables e-product and e-sale, to enhance their commercial function.

As a secondary hypothesis, the possibility exists that the e-sale variable is not correctly implemented, thus lacking full functionality.

The main objective of the paper presented herein is to analyze the evolution of the commercial function, since the arrival of the 2.0 model, on the official tourist websites of Spanish sun and sand destinations. This is the main engine of the Spanish tourism industry and consequently the most representative.

In order to contrast the previous hypotheses, the following specific objectives are proposed:

1. Determine if the websites under study include a section or sections oriented to the commercialization of the main tourist services: accommodation, transportation, catering and complementary activities; analyze their contents; and evolution (e-product).

2. Determine if the sections or sub-sections of the websites related to these services implement internal or exclusive applications or functionalities (managed by the OMD or by professional destination groups), for their purchase and / or reservation (e-sale). And analyze their evolution.

3. Study if these sections or subsections encourage the commercialization of the analyzed products and services by providing links to other websites (companies providing tourism products and services or private intermediaries) (e-sales). And analyze their evolution.

4. Analyze the flexibility of the system in terms of a variety of payment options: card, transfer, online payment systems, etc. (e-sale), and their evolution .

5. Evaluate the security of the offered payment systems (e-sale). Analyzing their evolution.

6. METHODOLOGY

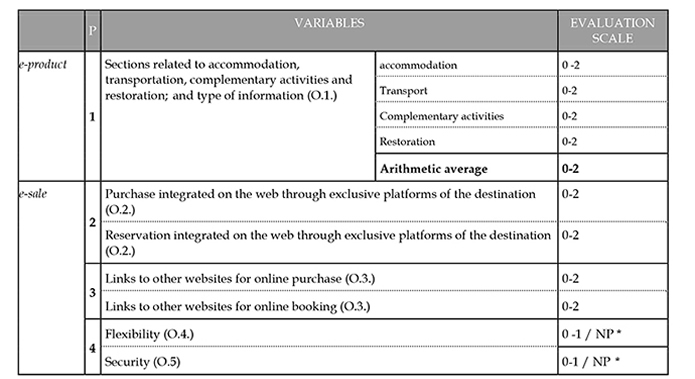

The methodology of this piece of research is empirical-analytical. It starts with a literature review on marketing and Internet in the tourism sector and the evolution of the commercial function of websites and, more specifically, official tourist websites. An exploratory study of the official Spanish tourist websites of the destinations focusing their offer on the sun and sand product is also carried out to evaluate the evolution of the implementation of commercial tools and functionalities since the arrival of model 2.0. Their analysis includes 4 parameters (P) according to the set objectives (Table 1). The description of the variables, their requirements and assessment scale can be consulted in the Annex.

Table 1. Summary of the analysis model of the commercial function on official tourist websites.

Source: Self-made. (*) Note: NP = Not applicable.

Data collection is based on an analysis of the content of the websites. The results are transferred to forms designed ex profeso, and inspired by analysis methodologies and previous research on official tourist websites (Díaz -Luque et al., 2006, Díaz -Luque et al., 2004, Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín, 2013, Fernández Cavia et al., 2013a, 2013b; Fernández-Cavia et al., 2013; Huertas Roig and Fernández Cavia, 2006 ), where they are quantified based on two scales. A binary scale (0-1) for analyzing flexibility and security and a 0-2 scale for all other variables as their indicators may occur, but not in optimal conditions.

The fieldwork has been carried out in two periods, March-August 2005 and January-May 2015, to analyze the evolution of the commercial function of the websites after the arrival of model 2.0.

Finally, the sample is composed of the websites of the sun and sand destinations of the Spanish autonomous communities with busiest international and national tourism (General Subdirectorate of Knowledge and Tourism Studies, 2014A, General Subdirectorate of Knowledge and Tourism Studies, 2014b).

Selection of websites was based on the following criteria: official capacity; regional, provincial, insular or municipal level; aimed at the final tourist and in full conditions of access and navigation (Table 2). The same sample has been maintained in the second phase of research, 2015, in order to analyze the evolution and thus verify the main hypothesis.

Table 2. Sample

Source: Self-made.

7. DISCUSSION AND RESULTS

7.1. Results of the analysis of the presence of sections related to: accommodation, transport, restoration and complementary activities; of the published information and their evolution (e-product)

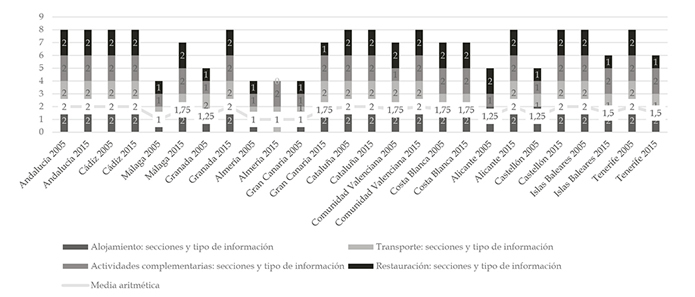

The analysis of the contents (Graph 3) confirms that most websites offer information regarding the services indicated as those susceptible to online reservation and / or purchase.

Source: Self-made.

Graph 3: Quantitative evaluation of the e-product variable .

In the first phase of research, all websites offer information related to the main services, with the exception of the Alicante website, in which no mention is made of transport services. Regarding the type of information provided, in general, information of a general and specific nature is offered. The websites that provide most information in the four areas are those of Andalusia, Cádiz, Balearic Islands, Tenerife and Catalonia.

In the second place are the websites offering generic and specific information, albeit partial, evaluated this way because they do not provide information on the four categories of products and services. This occurs mainly in relation to transportation on the Costa Blanca and Castellón websites, where the four main access routes are not considered. In addition, in the case of Castellón, there is also little information of a specific nature related to complementary activities and restoration, so it is cataloged in the third group. Also in second place are the websites in which the information, in most of the analyzed sections, is specific. This is the case, for example, of Valencia where, only in relation to complementary activities, information is not enough.

Third, there are websites the information of which, although specific, is characterized by being scarce. In this position you can find the websites of Málaga, Almería and Gran Canaria. The Granada website is also located in this last group because it basically offers generic information.

Regarding the evolution, it should be noted that, in general, the majority have improved in terms of quantity and quality of content. The websites of the Valencian Community, Alicante, Castellón and Granada achieve the maximum score since they have extended the initial contents related to accommodation, transport, complementary activities and restoration. Andalusia, Cádiz and Catalonia remain in the first group. Gran Canaria improves notably but does not reach the maximum score because, in relation to restoration, it only offers generic information. Costa Blanca and Almeria maintain the same score, the former because it continues to offer partial information regarding transportation; the latter because it does not offer any content on accommodation and restoration. Both sections are presented in the form of a search engine called “Partners” that does not show results. The title suggests that this is a section in development that will be completed with data from registered partners. Balearic Islands and Tenerife that, in the first phase of research, were in the first group lose this position. The former because, in the new version, it does not offer specific contents related to restoration. In the second case, the same thing happens and, in addition, the information relating to airlines is partial, only mentioning a local company, Binter, ignoring national and international ones.

From the analysis and the resulting arithmetic mean of the e-product variable, a categorization of the websites is established based on the following typology: category A (value 2); category B (values from 1.50 to 1.75); category C (values from 0.5 to 1.25) and category D (value 0) (Table 3).

Table 3. Categorization of official tourist websites based on the e-product variable (2005-2015)

Source: Self-made.

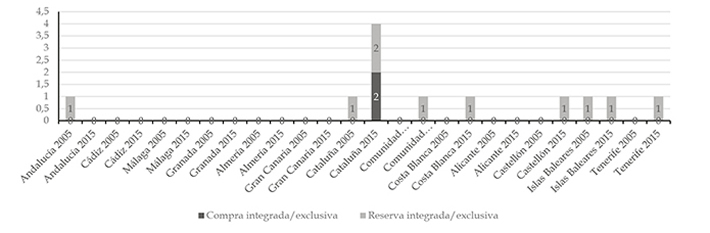

7.2. Results of the analysis of the commercial function through exclusive applications of the destination integrated on the web, and their evolution ( e-sale )

Source: Self-made.

Graph 4. Quantitative evaluation of the integrated and exclusive e-sale variable

In 2005 only three sites implement applications for compliance with the commercial function, and in all cases only the reservation of some products and services is allowed. Andalucía offers a link to its own platform, Seneca, consisting of a reservation head office for any tourism service in the eight Andalusian provinces, but it is not integrated on the web. Nor is the one offered by the Balearic Islands for the reservation of accommodations. It is managed by a group of hotel chains. Only Catalonia offers, exclusively and in an integrated manner, the possibility of reserving one of the four types of analyzed services: tickets for museums and monuments.

In the second phase of research and despite the technological development, the general situation is not very different. Andalusia no longer offers any commercial application. However, the Valencian Community and Costa Blanca have created an exclusive platform, Travel Open Apps, for the reservation of certain tourism products and services (accommodation, complementary activities and restoration), although the offer is not very complete. For example, in the field of restoration in Alicante, the searches carried out have not provided any results. Balearic Islands maintain the possibility of making accommodation reservations, but through another platform: Avanthotel.com, created by the federations and hotel associations of the destination. In all the cases described above, the user accesses these platforms leaving the website of origin. Only three web pages make up online reservation and / or purchase: Castellón, which allows online booking of rural tourism accommodation, Tenerife that incorporates a flight and golf course booking system, and Catalonia that offers a search engine called “Experiences” to make tourist packages composed of the four types of analyzed services, of all of them or of some of them. This search engine allows online reservation and / or purchase of said packages.

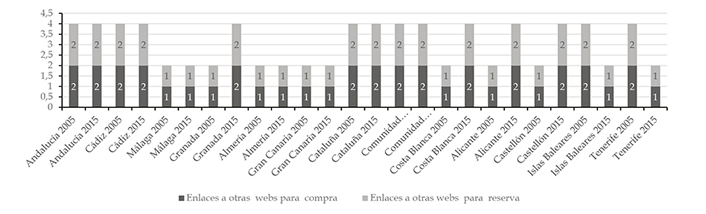

7.3. Results of the analysis of the commercial function through links to other websites (e-sale) , and their evolution

Source: Self-made.

Graph 5. Quantitative evaluation of the e-sale variable through links to other websites

In the first phase of research, the websites that obtain the worst scores in terms of content and information, Malaga, Almeria, Gran Canaria, Granada, Alicante and Castellón, are also the ones that offer less links, transport being the area with the greatest deficiencies, with the exception of Granada, which only refers to this service. Most sections related to products and services of accommodation, transport, complementary activities and restoration are presented as search engines in which users can delimit their searches through filters. The results obtained are usually links to more detailed files of the company in which photographs and basic data are provided, including the url.

In the second phase of research, the trend is maintained and the lowest-rated websites in terms of content are also mostly those that offer less links to other websites. Almería does not include any data or links of companies and organizations specialized in restoration and accommodation; The Balearic Islands and Tenerife offer partial information related to transport and only generic information in relation to restoration, and consequently they do not provide any links to websites of companies in this sector.

Some websites also offer links to platforms of private tourist intermediaries. This technique known as mashup is characteristic of the web 2.0 model and consists of adding and integrating content and services from more than one source with the aim of creating something new and with richer information content. In this line, in the first phase of research, Tenerife offers a flight search engine that links to the lastminute.com platform, although it is not operational. Alicante is another website that chooses to resort to this technique for transport services linking with platforms such as Hotels by Tripadvisor, Skyscanner, Jetcost, liligo.com, eDreams and Govoyages, or Rentalcars.com. Its search engines are integrated on the web. In the case of flights, even the results, but for reservation and purchase, the user is redirected from the web. Andalusia also resorts to this technique for the commercialization of air transport, restoration, sports activities (Golf) and accommodation services. Both the search engines and the results are integrated on the web, but as in the previous case, formalization can only be done by leaving the website of origin and accessing platforms such as Gotogate, Viajar, Tripsta, Tripair, lol, eDreams, for flights; Restaurants.com, for restoration; GolfSwitch , for golf; and Kayak, Tripadvisor and Trivago, for accommodation. In all cases, except for restoration, online purchases can be made. Málaga also redirects its users to the Booking.com platform after showing availabilities of accommodation on its website.

7.4. Results of the analysis of flexibility and security of payment, and of its evolution

In the first phase of research, none of the websites offers online purchase possibilities internally, so the analysis of this variable is applicable in none of the cases. In the second phase, only Catalonia. This website, as already explained, offers a search engine called “Experiences” that allows reservation and / or purchase. To do this, and after registering or providing basic data and password, it redirects the user to the BBVA bank website: Virtual POS. It only allows payment by credit card.

The analysis of the security of payment systems is also restricted to the website of Catalonia in its second analyzed version because it is the only one that offers the possibility of buying online by paying with the Visa and Mastercard cards. Both have accredited security systems: Verified by Visa and MasterCard SecureCode.

The following matrix shows the results obtained in relation to the evolution of the implementation of the e-sale variable

Table 4. Evolution of the implementation of the e-sale variable

Source: Self-made.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The results obtained herein allow us to conclude that the most representative destinations of the Spanish sun and sand tourism offer have implemented the e-product variable, integrating marketing 2.0 premises into their marketing strategies (Luque and Castañeda 2007). Their websites have evolved towards more commercial models, thus verifying the main hypothesis. However, except for Catalonia, they have not implemented another of the essential variables of marketing 2.0, e-sale (Sánchez, 2002). This also confirms the secondary hypothesis and explains in part why the online channel is still a channel of consultation in the tourism sector. OMDs still do not offer an integral tourist trip planning service (Díaz-Luque et al., 2004) despite the new technological tools and their responsibility in the promotion and commercialization of the destinations they represent (Martínez González, 2011). This is one of the contributions of this piece of research, necessary for the constant change that characterizes the online environment, and because it questions more optimistic conclusions, although referred to tourist websites in general (Martínez González, 2011).

Regarding the first hypothesis, the majority of the destinations analyzed herein have in the first phase of research a website oriented to the dissemination of the tourist offer, fulfilling a basically informative function. At that time, the Web 1.0 model prevailed, which was the focus of this function, and although distribution was also one of its objectives, the analysis showed that only a few websites considered it and incorporated the necessary tools and applications. They allowed online booking and their management depended on the OMD or professional associations of the destination, but only one, that of Catalonia, offered the integrated service on the website, avoiding a disruptive process of communication in the development of online purchase (Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín, 2013) and favoring the usability of the web (Nielsen, 1997) .

In this regard and in relation to the second hypothesis, although in 2015 there are more websites that incorporate exclusive marketing tools, they are generally limited to reserving some of the analyzed products or services. Only Catalonia allows the purchase of the four, without leaving the website, except to make the payment. The alternative to exclusive platforms, that is, the inclusion of links to the corporate websites of the tourist service providers, in 2005 was not a usual practice either. Only 46.5% of the websites offered the necessary links so that users could formalize the tourist trip on the Internet. In the second phase of research, except the websites of the Balearic Islands and Tenerife, all improve their score relative to the information about the products and services, or maintain it, thus verifying the first hypothesis in regard to the e-product variable. This positively influences the number of links to corporate websites of organizations that provide tourism products and services. But in addition, it is observed that some websites implement mashup that allows online purchase and / or booking through links to platforms of private tourist intermediaries such as: Hotels by Tripadvisor, Skyscanner, Jetcost, Liligo.com, eDreams, Trivago, Booking.com, etc. This technique easily and economically solves the commercial function of the web and is a solution for the OMDs to assume their role as tourist intermediaries ( Díaz-Luque et al., 2004; Díaz-Luque et al., 2006; Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín., 2013, Fernández Cavia et al., 2013, Huertas Roig and Fernández Cavia, 2006). However, its implementation still has deficiencies that can be remedied in terms of usability. Platforms must be integrated onto the websites and the user should not be forced to leave them, generating confusion and possible leaks (Nielsen, 1997). The results obtained herein, as has been advanced, verify the two hypotheses, given that the commercial function, although assumed, as evidenced by the positive evolution of the e-product variable, is not correctly implemented, thus lacking full functionality.

The results confirm those of previous studies such as those by Díaz-Luque et al. (2004), Díaz-Luque et al. (2006), Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín (2013), Huertas Roig and Fernández Cavia (2006) and Fernández Cavia et al. (2013a) that conclude the need to improve e-commerce services to prevent leakage of potential tourists. For this, OMDs have different alternatives that must be analyzed and evaluated based on their advantages and disadvantages. This piece of research helps to establish them. Relegate the commercialization of tourism products and services to the corporate websites of supplier companies, although it is an economical solution, entails several risks. Not only does it force the user to leave the website but there is also a danger that they do not offer online purchase and / or reservation services, as evidenced by the piece of research carried out by Martínez María-Dolores, Bernal García and Mellinas Canovas (2013). Own systems report great benefits (Díaz-Luque, Guevara, Caro and Aguayo, 2008, Díaz-Luque and Jiménez Marín, 2013) but their development and maintenance imply significant human and material costs. They can be avoided through links to platforms created by private tourism intermediaries, which enjoy greater notoriety and credibility and have greater economic and material resources, which gives them an advantageous position. The problem is that they offer the same services as competitive tourist destinations. An intermediate solution is the transfer of online commercial exploitation of products and services to companies in the tourism sector of the destination, following the neopublic trends of administrative management (Campillo Alhama, 2013). This avoids the costs of creation and development, and the presence of competitors of the destination in the system, although these platforms do not have the same audience as the private ones. Without a doubt, the final decision depends on the positioning of the destination in the market and the objectives, strategies and means at its disposal.

In relation to the last two indicators related to the e-sale variable, the results are conclusive. Greater flexibility is required, providing at least the most widely accepted payment methods: Paypal system and debit cards (Cetelem, 2015, IAB Spain and Viko we are, 2015). The first one is also preferred for its safety (IAB Spain and Viko we are, 2015). In the case of security, it must be guaranteed through systems that have the backing of credible and prestigious banking entities, as in the analyzed case. What reaffirms the secondary hypothesis.

A reality has been described in which the online channel is a key and present element throughout the tourism process. The evolution of the merely informative websites of destinations to those that include marketing services, the mass development of platforms marketing hotels, flights, etc., and low cost, are some examples of a tourism reality marked by technology. OMDs must understand and manage the changes that are taking place and use all the tools that are offered to them and yet there is deficient implementation of the e-sale variable and consequently of the premises of marketing 2.0.

The importance of the official website in the tourism sector and the constant evolution that characterizes the online environment lay the foundations of a research field without any limits as long as the Internet continues to develop. Research carried out has revealed relevant issues in relation to the search systems and their usability, as well as the convenience or not of developing online reservation and purchase platforms. It is also intended to continue this research by expanding the sample size to include international destinations the offer of which is based on the sun and sand product and other national ones such as Tarragona, Gerona, Murcia, etc., which have developed websites likely to be part of the scope of study.

REFERENCES

1. Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación (2016). 18º Navegantes en la Red. Encuesta AIMC a usuarios de Internet Marzo 2016. Recuperado de http://download.aimc.es/aimc/ROY76b/macro2015.pdf

2. Bigné-Alcañiz JE (1996). Turismo y marketing en España. Análisis del estado de la cuestión y perspectivas de futuro. Estudios Turísticos, 129, 105-127.

3. Buhalis D, Law R (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—the state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609-623. Doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

4. Campilllo-Alhama C (2013). La administración municipal relacional y participativa. Cómo construir la identidad de las ciudades desde una perspectiva de comunicación neopública. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 30, 74-93. Doi: 10.15198/seeci.2013.30.74-93

5. Caro JL, Luque A, Zayas B (2015). Nuevas tecnologías para la interpretación y promoción de los recursos turísticos culturales. Pasos Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio cultural, 13(4), 931-945.

6. Cetelem (2015). El Observatorio Cetelem 2015 e-Commerce. Recuperado de http://www.elobservatoriocetelem.es/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/observatorio-cetelem-ecommerce-2015.pdf

7. Cortés M (2009). Bienvenido al nuevo marketing. En E. San Agustín, (ed.). Del 1.0 al 2.0: Claves para entender el nuevo marketing (pp. 6-23). Recuperado de http://uphm.edu.mx/libros/clavesdelnuevomarketing.pdf

8. Díaz-Luque P, Guevara-Plaza A, Antón-Clavé S (2006). La presencia en Internet de los municipios turísticos de sol y playa. Mediterráneo y Canarias, en Aguayo-Maldonado A, Caro-Herrero JL, Gómez-Gallego I, Guevara-Plaza A (Eds.). VI Congreso Nacional Turismo y Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. Turitec 2006 (pp. 423-445). Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, Escuela Universitaria de Turismo.

9. Díaz-Luque P, Guevara-Plaza A, Caro-Herrero JL (2004). Promoción turística de las Comunidades Autónomas en Internet, en Aguayo-Maldonado A, Caro-Herrero JL, Gómez-Gallego I, Guevara-Plaza A (Eds.). V Congreso Nacional de Turismo y Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. Turitec 2004 (pp. 35-52). Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, Escuela Universitaria de Turismo.

10. Díaz-Luque P, Guevara A, Caro JL, Aguayo A (2008). Descubriendo las razones para introducir el comercio electrónico en las webs de destinos turísticos, en Guevara-Plaza A; Caro-Herrero JL, Aguayo-Maldonado A (Eds.). VII Congreso Nacional de Turismo y Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. Turitec 2008 (pp. 189-202). Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, Escuela Universitaria de Turismo.

11. Díaz-Luque P, Jiménez-Marín G (2013). La web como herramienta de comunicación y distribución de destinos turísticos. Questiones publicitarias, 1(18):39-55.

12. Domínguez-Vila T, Araújo-Vila N (2014). Gestión de las redes sociales turísticas en la web 2.0. Vivat Academia, Revista de Comunicación, 129:57-78. Doi: 10.15178/va.2014.129.57-78

13. Duncan-Ortega EM (2009). The Internet Effects on Tourism Industry. Social Science Research Network, SRRN. Doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1403087

14. Fernández-Cavia J, Díaz-Luque P, Huertas A, Rovira C, Pedraza-Jiménez R, Sicilia M, Gómez L, Míguez M, 2013. Marcas de destino y evaluación de sitios web: una metodología de investigación. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 68 (993):622-638. Doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2013-993

15. Fernández-Cavia J, Vinyals-Miraben S, López-Pérez M (2013a). Calidad de los sitios web turísticos oficiales de las comunidades autónomas españolas. BiD: textos universitaris de biblioteconomia i documentació. Facultat de biblioteconomia i Documentació, Universitat de Barcelona, 31. Doi: 10.1344/BiD2014.31.7

16. Fernández-Cavia J, Vinyals-Mirabent S, López-Pérez M (2013b). Plantilla de análisis. Marcas turísticas. Marzo 2013. En http://www.marcasturísticas.org. Recuperado de http://www.marcasturisticas.org/images/stories/resultados/plantilla_marzo2013_versionweb.pdf.

17. Google Travel Spain; Instituto de Estudios Turísticos; Exceltur; Allianz; Secretaría de Estado de Turismo del Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Turismo del gobierno de España & Added Value (2013). Lookinside Travel. Estudio sobre el viajero español, 2012. Recuperado de http://es.slideshare.net/mcolmenero769/estudio-del-viajero-espaol-2012.

18. Hallet R, Kaplan-Weinger J (2010). Official tourism websites: a discourse analysis perspective. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

19. Huertas-Roig A, Fernández-Cavia J (2006). Ciudades en la web: Usabilidad e interactividad de las páginas oficiales de los destinos turísticos, en Aguayo-Maldonado A, Caro-Herrero JL, Gómez-Gallego I, Guevara-Plaza A (Eds.). VI Congreso Nacional Turismo y Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones. Turitec 2006 (pp. 403-421). Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, Escuela Universitaria de Turismo.

20. Institute Advertising Bureau Spain Research & Viko we are (2015). Estudio eCommerce 2015 IAB Spain. Recuperado de http://www.iabspain.net/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2015/06/Estudio-ecommerce-2015-IAB-abierta.pdf

21. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2013). Encuesta de uso de TIC y Comercio Electrónico en las empresas (20 de Junio de 2013). Recuperado de http://www.ontsi.red.es/ontsi/es/indicador/volumen-de-negocio-de-comercio-electr%C3%B3nico-en-espa%C3%B1a.

22. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2014). Encuesta sobre el uso de Tecnologías de la información y las Comunicaciones (TIC) y del comercio electrónico en las empresas (19 de septiembre de 2014). Recuperado de http://www.ine.es/prensa/np859.pdf

23. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2015). Encuesta sobre el uso de Tecnologías de la información y las Comunicaciones (TIC) y del comercio electrónico en las empresas (26 de junio de 2015). Recuperado de http://www.ine.es/prensa/np918.pdf

24. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2016). Encuesta sobre el uso de Tecnologías de la información y las Comunicaciones (TIC) y del comercio electrónico en las empresas (28 de junio de 2016). Recuperado de http://www.ine.es/prensa/np978.pdf

25. International Organization for Standarization (1998). ISO/IEC 9241-11: Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs). Part 11: Guidance on usability. Ginebra: International Standards Organization

26. Lacalle CH (2011). La ficción interactiva: Televisión y Web 2.0. Ámbitos, 20:87-107.

27. Lanquar R (2001). Marketing turístico. Barcelona: Ariel Turismo, Colección AECIT.

28. Law R, Qui S, Buhalis D (2010). Progress in tourism management: a review of website evaluation in tourism research. Tourism Management, 31(3):297-313. Doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.11.007

29. Lee W, Gretzel U (2012). Designing persuasive destination websites: a mental imagery processing perspective. Tourism Management, 33(5):1270-1280. Doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.10.012

30. López-Sánchez JA, Chica-Ruiz JA, Arcila-Garrido M, Azzariohi A, Soto-Benito A (2010). Modelo de análisis de páginas Web turísticas en Andalucía. Historia actual online - HAOL, (22):185-200. Recuperado de http://www.historia-actual.org/Publicaciones/index.php/haol/article/view/477/385

31. Luna-Nevarez C, Hyman M (2012). Common practices in destination website design. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(12):94-106. Doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.08.002

32. Luque T, Castañeda JA (2007). Internet y el valor del negocio. Mediterráneo económico, 11:397-415.

33. Martínez-González JA (2011). Marketing turístico online. TURyDES Revista de investigación y desarrollo local, 4(9). Recuperado de http://www.eumed.net/rev/turydes/09/jamg2.htm

34. Martínez-María-Dolores SM, Bernal-García JJ, Mellinas-Cánovas JP (2013). Análisis del nivel de presencia de los establecimientos hoteleros de la región de Murcia en la web 2.0. Cuadernos de Turismo, 31:245-261.

35. Mediano-Serrano L (2002). Un caso de marketing turístico: el agroturismo en el País Vasco. Cuadernos de Gestión, 1(2):55-68.

36. Nafría I (2008). Web 2.0 El usuario, el nuevo rey de Internet. Barcelona: Ediciones Gestión 2000-Planeta De Agostini Profesional y formación S.L, Gestión 2000.

37. Nielsen J (1 diciembre 1997). Changes in Web Usability Since 1994, en Nngroup.com NN/g Nielsen Norman Group. Articles. Recuperado de http://www.nngroup.com/articles/changes-in-web-usability-since-1994/

38. Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información, 2007. Estudio sobre comercio electrónico B2C 2007. Recuperado de http://www.ontsi.red.es/ontsi/eu/estudios-informes/estudio-sobre-comercio-electr%C3%B3nico-b2c-2007-del-observatorio-de-las-telecomunicaci

39. Organización Mundial del Turismo (1999). Promoción de Destinos Turísticos en el Ciberespacio, Retos del Marketing Electrónico. Madrid: Consejo Empresarial de la OMT.

40. Organización Mundial del Turismo (2001). Comercio Electrónico y Turismo: Guía Práctica para Destinos y Empresas. Madrid: Consejo Empresarial de la OMT.

41. O´Reilly T (30 septiembre 2005). What is the Web 2.0. Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. O´Reilly.com. Recuperado de http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

42. Palmer A (2005). The Internet challenge for destination marketing organizations. En Morgan N, Pritchard A, Pride R (Eds.). Destination branding: creating the unique destination proposition (pp. 128-140). Oxford: Elsevier.

43. Park YA, Gretzel U (2007). Success factors for destination marketing web sites: a qualitative meta-analysis. Journal of travel research, 46(1):46-63. Doi: 10.1177/0047287507302381

44. Polo D (2009). La filosofía 2.0 y la explosión audiovisual en Internet. Razón y palabra, 7:87-96.

45. Rastrollo-Horrillo MA, Alarcón-Urbistondo P (1999). El turista ante el comercio electrónico. Revista de Estudios Turísticos, 142:97-116.

46. Sánchez G (2002). Las etapas del cambio hacia la venta por Internet. Algunas consideraciones al respecto. Alta dirección, 38(223):19-28.

47. Suau-Jiménez F (2012). El turista 2.0 como receptor de la promoción turística: estrategias lingüísticas e importancia de su estudio. Pasos, Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 10(4):143-153.

48. Subdirección General de Conocimientos y Estudios Turísticos, 2014a. Movimientos turísticos en fronteras (FRONTUR). Recuperado de https://goo.gl/1nP1cS

49. Subdirección General de Conocimientos y Estudios Turísticos, 2014b. Movimientos turísticos de los españoles (FAMILITUR). Recuperado de https://goo.gl/t9P74c

50. Subdirección General de Conocimientos y Estudios Turísticos, Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Turismo del gobierno de España & Instituto de Turismo de España, 2016. Informe de boletín trimestral de coyuntura turística (COYUNTUR). Recuperado de https://goo.gl/6XeEag

51. Yeung TA, Law R (2006). Evaluation of Usability: A Study of Hotel Web Sites in Hong Kong. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 30(4), 452-473. doi: 10.1177/1096348006290115

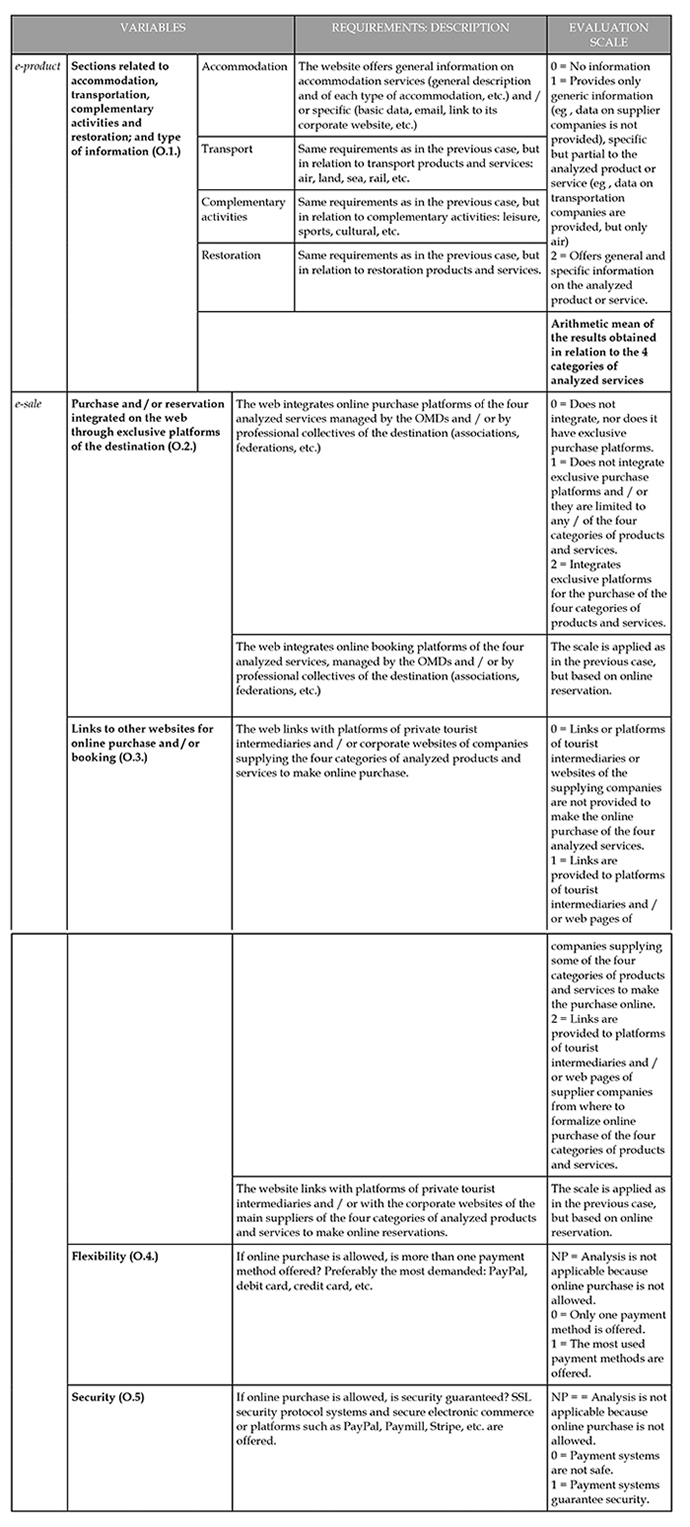

ANNEXED

Analysis model of the commercial function in official tourist websites

Source: Self-made

AUTHOR

Alba-María Martínez-Sala

Bachelor’s degree in Information Sciences (Advertising and Public Relations) from the Complutense University of Madrid and Doctor of Fine Arts (art and graphic design) from Miguel Hernández University. Teacher in the Degree of Advertising and Public Relations, in the field of advertising and public relations strategy at the University of Alicante and in the Official Master in Organization of Events, Protocol and Institutional Relations of IMEP, in the field of events and relational marketing. She has also performed her professional activity in several private organizations. Her main lines of research are digital communication in the public and private sector, specifically in the tourist institutional sector and in the franchise company. She belongs to the Compubes research group at the University of Alicante.

http: // orcid.org/0000-0002-6852-6258

https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=O9-_0goAAAAJ