10.15178/va.2018.143.25-44

RESEARCH

COMMUNICATION IN THE THIRD SECTOR: THE CASE IN VALLADOLID

LA COMUNICACIÓN EN EL TERCER SECTOR: EL CASO VALLISOLETANO

A COMUNICAÇAO NO TERCEIRO SETOR: O CASO VALLISOLETANO

Begoña Gómez-Nieto1 Es profesora agregada de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales. Doctora en Ciencias de la Información por el IE Universidad de Segovia y licenciada en Comunicación por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Mª-del-Mar Soria-Ibáñez1

Beatriz Concejo-Ulloa1

1European University Miguel de Cervantes. Spain

ABSTRACT

The Third Sector (TS) springs from the need to generate a new agent between the public and the private sector that could therefore be an entity that represents the citizenry. In Spain, the history of NGOs shows that they have been organizations linked to public power, since their introduction as welfare organizations after the civil war. The objective of this paper is to perform an exhaustive analysis of the communication of the Third Sector in general and, in particular, in the city of Valladolid. We develop a deep analysis of the use of communication made by local organizations. As a methodology, we have used the quantitative research technique. The technique allows us to obtain inferences about the image of non-profit organizations of Valladolid before the citizenry. We have found out that the main source of funding comes from the public sector, which is why the traditional budget management model followed by the Third Sector in Spain persists. In addition, entities have more volunteers than workers and these organizations use new technologies to contact their public, although the surveyed citizens state that they are not receiving messages sent by NGOs, and they consider that they do not effectively manage their communication.

KEY WORDS: The Third Sector; Social Communication; Valladolid; NGO; Solidarity values; Social Action; Organizational Communication

RESUMEN

El Tercer Sector (TS) nace de la necesidad de generar un nuevo agente entre el sector público y el privado, y que por lo tanto represente a la ciudadanía. En España, la historia de las ONG demuestra que han sido organizaciones ligadas al poder público, desde su introducción como entidades asistencialistas tras la guerra civil. El objetivo de este trabajo, es realizar un análisis exhaustivo de la comunicación del Tercer Sector de modo general, y en particular, en la ciudad de Valladolid. Se desarrolla un profundo análisis del uso de la comunicación que hacen las entidades locales. Como metodología se ha empleado la técnica de investigación cuantitativa: cuestionario. La técnica permite obtener inferencias sobre la imagen que tienen las organizaciones no lucrativas de Valladolid frente a la ciudadanía. Entre los resultados destacamos que la principal fuente de financiación procede del ámbito público, por lo que persiste el modelo tradicional de gestión presupuestaria que siguen los organismos del Tercer Sector en España. Además, las entidades disponen de más voluntarios que trabajadores y utilizan las nuevas tecnologías para contactar con su público, aunque la ciudadanía encuestada manifiesta que no es receptora de los mensajes emitidos por las ONG, y consideran que no gestionan eficazmente su comunicación.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Tercer Sector; Comunicación Social; Valladolid; ONG’s; valores solidarios; Acción Social; Comunicación organizacional

RESUME

O terceiro Setor TS nasce da necessidade de gerar um novo agente entre o setor público e o privado, e portanto, represente a cidadania. Na Espanha, a história das ONGs demonstra que foram organizações ligadas ao poder público, desde sua introdução como entidades assistenciais após a guerra civil. O objetivo desse trabalho é realizar uma analises exaustiva da comunicação do Terceiro Setor de modo geral, e em particular, na cidade de Valladolid. Se desenvolve uma profunda analises do uso da comunicação que fazem as entidades locais. Como metodologia foi empregada a técnica de investigação quantitativa: questionário. A técnica permite obter inferências sobre a imagem que tem as organizações não lucrativas de Valladolid frente a cidadania. Entre os resultados destacamos que a principal fonte de financiação procede do âmbito público, persistindo o modelo tradicional de gestão orçamentária que seguem os organismos do Terceiro Setor na Espanha. Ademais, as entidades dispõem de mais voluntários que trabalhadores e utilizam as novas tecnologias para contatar com seu público, apesar que a cidadania questionada, manifesta que não estão de acorde com as mensagens emitidas pelas ONGs e consideram que não gestionam eficazmente sua comunicação.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Terceiro setor; Comunicação social; Valladolid; ONGs; Valores solidários; Ação social; Comunicação organizacional.

Received: 23/11/2017

Accepted: 17/01/2017

Correspondence: Begoña Gómez Nieto

mbgomez@uemc.es

Mª del Mar Soria Ibáñez

mmsoria@uemc.es

Beatriz Concejo Ulloa:

bconcejo5229@alumnos.uemc.es

Cómo citar el artículo

Gómez Nieto, B., Soria Ibáñez, Mª del Mar y Concejo Ulloa, B. (2018). The communication in the third sector: the case in Valladolid. [La comunicación en el tercer sector: el caso Vallisoletano]

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 143, 25-44

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.143.25-44

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1063

1. INTRODUCTION

The Third Sector springs from the need to end inequalities and to establish equal rights for all people. It is an increasingly important actor in structuring and solving the growing demands and initiatives of civil society. Its relevance is reflected in dimensions such as the number of organizations that make it up, the multiplicity of social demands that they satisfy, the dimensions of social investment, the number of beneficiaries they serve, the jobs they generate, and the volunteering they mobilize. Therefore, the object of study presents this environment, analyzing the specific case of the city of Valladolid.

The definition of the Third Sector is a subject that has generated much controversy. Depending on the point of view we take, we can define it for what it is, or for what it is not. For this reason, the borders when delimiting it have almost never been concretized in an exhaustive way or are very varied and different.

For this study, we take as reference the Yearbook of the Third Sector of Social Action (TSAS) in Spain (2016) which, with professors Rodríguez Cabrero and Marbán (2008), refer to this definition referring to “the difficulties of the internal delimitation of the TS and of this with the commercial company, especially in the border areas of the social economy and of the company foundations”.

In the definition of the Third Sector, there are mainly two approaches: on the one hand, from Social Economy (continental European tradition) the important thing is the democratic dimension of organizations and production for the market of social goods. On the other hand, from the Non-Profit Sector (Anglo-Saxon tradition) the importance of non-distribution of benefits by entities stands out as well as the importance of volunteering.

The approach acquired by the Yearbook is that which identifies the Third Sector with Non-Profit Sector. Thus, to belong to the Third Sector, they have to comply with the operational definition adopted by the study led by the team at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore (Salamon and Anheier, 1997). These criteria were later assumed by the UN in the publication The Handbook on Non-Profit Institutions in the System of National Accounts. They are the following: be formally organized; be private; absence of profit motive; enjoy the capacity for institutional self-control of their activities; have some degree of voluntary participation.

Based on these characteristics, we can check which typology of organizations are behind the concept of the Non-Profit Entity and which are not (Balas, 2011: 43). The following are included in the Third Sector (Urban Economy, 2010): Civil Society: Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Non-Governmental Organizations for Development (NGDOs); Social Economy: Cooperatives and Mutualities; Voluntary Associationism: Foundations and Associations; Non-Profit Sector: Not-for-Profit Companies (ESAL), Non-Profit Entities (ENL) and Cooperation Entities. The following are excluded from the Third Sector: Churches, Labor Unions and Political Parties, Business and Professional Associations, Professional Sports Associations, Local Neighborhood Communities, Business and Philanthropic Foundations, Health Entities.

1.1. Evolution of the Third Sector in Spain

The decade of the 1990s is considered the beginning of the Third Sector in Spain (Study on the present and future of the Third Social Sector in a crisis environment, 2016). These entities are born through the private boost, which is considered almost one hundred percent. From 1990 to 2000, mixed financing began. The driving force behind this was the 0.7% Movement. This initiative emerged at the UN in the 1940s, but it is not until the 1992 United Nations Summit in Rio when it is reaffirmed by all the political parties in Spain (Plataforma07.org, 2016).

From 2000 to 2008, the domain of financing was public. The economic crisis that began in 2008 in Spain affected all types of organizations. In fact, in recent years, 84% ??of Spanish non-profit entities have been forced to reduce their budgets. Almost a half, 48%, has lost 10% to 20% of their usual budget items, while 25% of organizations have lost 30 to 40% (Fundación Mutua Madrileña, 2014, p. 3). 2012 was a year of inflection for the TS due to the following factors of public financing: budget cuts, difficulty in collecting budgeted funds, difficulties in accessing credit and making it more expensive, and the reduction of the rights guarantee framework of the administration.

To Marcuello (1996, p. 107), an NGO is defined as an “organization that have their origin in civil society, that have transcendence in international action and that occupy a position different from that of governments “.

Granda and Lutz (1988, p. 13), on the other hand, point out that they are autonomous and independent organizations from the scope of governments (although they can carry out joint activities and even receive part of their resources from them), they are not for profit and their resources are used to finance projects in the field of development cooperation.

According to Herranz de la Casa (2006, p. 30), the Third Sector emerges as an alternative to the lucrative logic of the traditional capitalist economy (second sector / market) and the shortcomings of the public economy (first institutional sector / Administration -State). It is defined as a plural, diverse and heterogeneous reality both in terms of the typology of the institutions that form it and its size, territorial scope or orientation of the service they perform.

Thus, and under the aforementioned definitions, we can affirm that Third Sector organizations, and more specifically those that work in development cooperation, must have a citizen origin (Gómez Gil, 2005, p. 23). Currently, Spanish NGOs have seen their income shrink considerably, since a large part of them depended on public budgets. In the case of Castilla and León, this decrease has affected 65% of the budgets of the cooperation entities in the region. The consequences for these organizations in the national panorama and, in a more concrete way, in Castile and León, have been translated into records of employment regulation, non-renewal of contracts (as in Ayuda en Acción or Intermón Oxfam), disappearance of entities and closure of venues (Proyecto Hombre). In this framework, non-governmental organizations that work for development are forced to reinvent themselves and continuously adapt to social needs and the challenges of citizen transformation. The crisis, at this point, can be understood as an opportunity.

There is no doubt about the importance of strategic communication management for this type of entities that, at the present time and as mentioned, have seen their budgets to execute projects decrease significantly (Ramírez, 1995, p. 32). As a result of the appearance of the first departments dedicated to communication management, NGOs begin to acquire a presence in the media (Gómez Gil, 2005, p. 80). But it was not until the nineties that Spanish NGOs began to be visible in the media (Sampedro et al., 2002, p. 275). This was thanks to the fact that various business organizations and some social organizations gave a definitive boost to their communication at this stage, as in the case of Médicos Sin Fronteras (Almansa, 2003, p. 107).

One of the mistakes of the Spanish NGOs was to provide information to all the journalists who requested it. This way, dramatic and virulent images were provided, with the aim that journalists would not stop being interested in them (González Luis, 2006, p. 73). However, and despite the fact that we mentioned that the communication departments of Spanish NGOs did not begin to be a reality until the mid-nineties (García Orosa, 2006, p. 57).

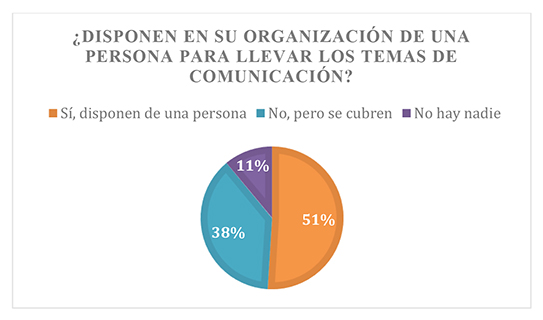

On the other hand, we can affirm that the question of the creation of a communication department is determined by the budget of the organization (Soria, 2011). Regarding the availability of people to manage communication issues, Balas (2011, p. 214) presents the following data (Picture 1):

Source: Balas (2011, p. 214)

Picture 1. Employees responsible for communication in organizations

The high qualification of the people who carry out communication in the entities of the Third Sector stands out. 78% have university studies and 6% have medium-level studies. But, the higher education they have draws attention, most have degrees in the field of the organization, as compared to a minority in the field of Communication Sciences.

One of the most reliable indicators to assess the level of implementation of communication policies in Third Sector organizations is the global budget dedicated for these purposes. 47% less than 2% of the global budget, 17% do not contribute anything and 13% contribute 5%. Thus, we observe that communication counts on scarce economic resources.

2. OBJECTIVES

The objectives proposed for this piece of research are the following:

– Analyze which the main sources of funding for Valladolid’s NGOs are, as well as their resources.

– Evaluate the staff that works in this type of organizations: workers versus volunteers

– Determine which of them have a communication department, in order to check whether the fact that they depend on a global entity favors their operation.

– What is the structure, resources (use of new technologies), staff of local communication departments?

– How does this type of Third Sector entities manage communication?

3. METHODOLOGY

The selected research technique was the questionnaire. We have carried out surveys in two directions: on the one hand, the organization as such (38 organizations, of which 65.78% responded) and, on the other hand, a sample of Valladolid society (we sent 200 surveys of which we obtained 50% as response). We have chosen the technique of the questionnaire because it is a support that gathers the questions that are formulated to the people selected in the sample. This means allows communication between interviewer and interviewee, to obtain the information provided in the survey design (Trespalacios, 2005, p. 126). The survey can be defined as “a particular interrogation regarding a situation that includes certain individuals with the objective of establishing a generalization” (Matalon and Ghiglione, 1989, p. 13).

In addition, the data that can be obtained with this technique belong to categories, which fit in the objectives we want to fulfill with this piece of research (García Muñoz, 2003): facts, opinions, attitudes and cognitions.

We obtain this data through open questions, so that each respondent is free to show their opinions, and closed questions to mark the response items that we want to research. Within the latter we will use dichotomous questions, univariate, multivariate and scale multianswer.

To determine the sample, we considered criteria as a starting point, that is, requirements that organizations must meet:

– Have partners: to know what is the predominant form of financing.

– Have volunteers to help them in their field of action and know what percentage they occupy within the organization.

– Have employees among their staff, to be able to compare the number of volunteers with the permanent employees.

With these requirements, we sent the questionnaire to 38 organizations, 25 out of which answered, that is, 65.78%. For its realization, we addressed the person in charge of communication, be it the head of the communication department of the entity or an employee who is dedicated to perform these functions. These entities are the following:

1. ACCIÓN VERAPAZ: valladolid@accionverapaz.org

2. AMYCOS: valladolid@amycos.org

3. ARQUITECTO SIN FRONTERAS DE CASTILLA Y LEÓN: asfcyl@hotmail.com

4. ARQUITECTOS SIN FRONTERAS CYL: asfcyl@hotmail.com

5. ASAMBLEA DE COOPERACION POR LA PAZ DE CASTILLA Y LEON: castillayleon@acpp.com

6. ASOC. CULT. AMIGOS PUEBLO SAHARAUI: saharacyl@gmail.com

7. ASOCIACIÓN ALBA: SIJ@asociacionalba.org

8. ASOCIACION COOPERACION SOCIAL DE CYL COSOCIAL: cosocial.valladolid@gmail.com

9. ASOCIACIÓN MUNDO COPERANTE DE CASTILLA Y LEÓN: castillaleon@mundocooperante.org

10. ASOCIACION UMOYA: valladolid@umoya.org

11. AZACAN SERSO CYL: info@azacan.org

12. CÁRITAS: diocesana@caritasvalladolid.org

13. CRUZ ROJA: valladolid@cruzroja.es

14. EDUCA TANZANIA: info@educatanzania.org

15. ENTRECULTURAS: valladolid@entreculturas.org

16. ENTREPUEBLOS: ep.valladolid@entrepueblos.org

17. FSIC: castillayleon@fisc-ongd.org

18. FUNDACIÓN ADSIS: Valladolid@fundacionadsis.org

19. FUNDACIÓN ÁFRICA DIRECTO: Juana.moreno@telefonica.net

20. FUNDACIÓN BANCO DE ALIMENTOS: valladolid@bancodealimentos.info

21. FUNDACIÓN CAUCE: info@fundacioncauce.org

22. FUNDACIÓN INTRAS: intras@intras.es

23. FUNDACIÓN MAINEL: fernando@mainel.org

24. FUNDACIÓN RED DEPORTE Y COOPERACIÓN: rdc@redeporte.org

25. GAM TEPEYAC: gam@uva.es

26. HAREN ALDE: castillayleon@harenalde.org

27. INGENIERÍA SIN FRONTERAS: comunicacion@cyl.isf.es

28. INGENIERÍA SIN FRONTERAS: comunicacion@cyl.isf.es

29. INTERED: castillaleon@intered.org

30. INTERMON OXFAM: cvalladolid@oxfamintermon.org

31. MANOS UNIDAS: valladolid@manosunidas.org

32. MISIÓN AMÉRICA: misionvalladolid@hotmail.es

33. ONG CEBÚ: cebu@ongcebu.org

34. PROCLADE: castillaleon@fundacionproclade.org

35. PROYDE: noroeste@proyde.org

36. PUENTES ONG: puentesongd@yahoo.es

37. RED MADRE VALLADOLID: infovalladolid@redmadre.es

38. UNICEF: rgutierrez@unicef.es

4. DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF RESULTS

In order to interpret the results, we must point out that we have divided them into four blocks that respond to the following sections: structure of the entities, communication, new communication technologies and impact on society.

4.1. Structure of the entities

Regarding the structure of the entities, we pointed out the following data:

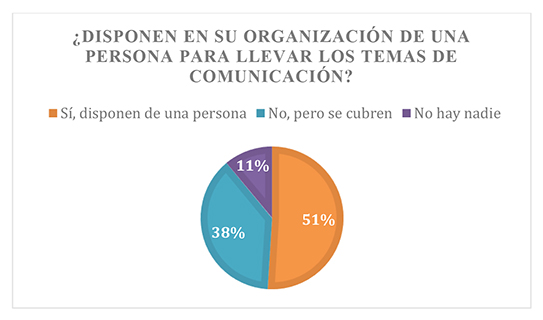

The first question we asked ourselves is: what are the forms of financing of the Valladolid entities of the Third Sector? (Picture 2) From the financing obtained all the actions of the entity will be developed one way or another. 62% of surveyed entities have public funding as the predominant form of financing. Half, 31% are paid mainly with the capital contributed by the partners and only 8% thanks to commercial actions. None of them has chosen equity returns as a form of financing.

Source: Self-made

Picture 2. Forms of financing.

Therefore, we can affirm that the predominant form of financing of the TS entities of Valladolid is public financing.

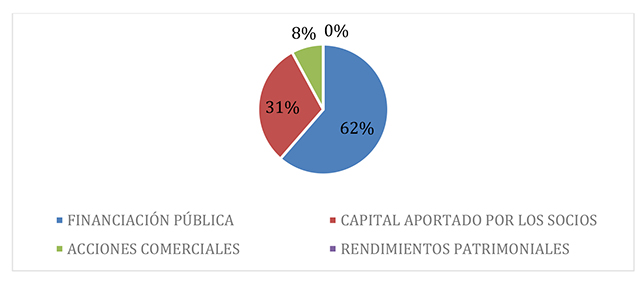

After analyzing the predominant form of financing, we focused on what the human resources available to Third Sector organizations in this city are.

To answer this question, we divided these resources between contracted personnel and volunteers. Thus, 62% of the entities have less than 10 employees in their staff, only 8% have more than 51 employees. On the other hand, the number of volunteers is equated to the proposed ranges, with 31% being higher, from 11 to 25 volunteers (Picture 3)

Source: Self-made

Picture 3. Comparison between the number of volunteers and workers.

Thus, we respond that the number of volunteers is larger than that of workers. In addition, 53% of the entities think that the number of volunteers must be the largest within human resources.

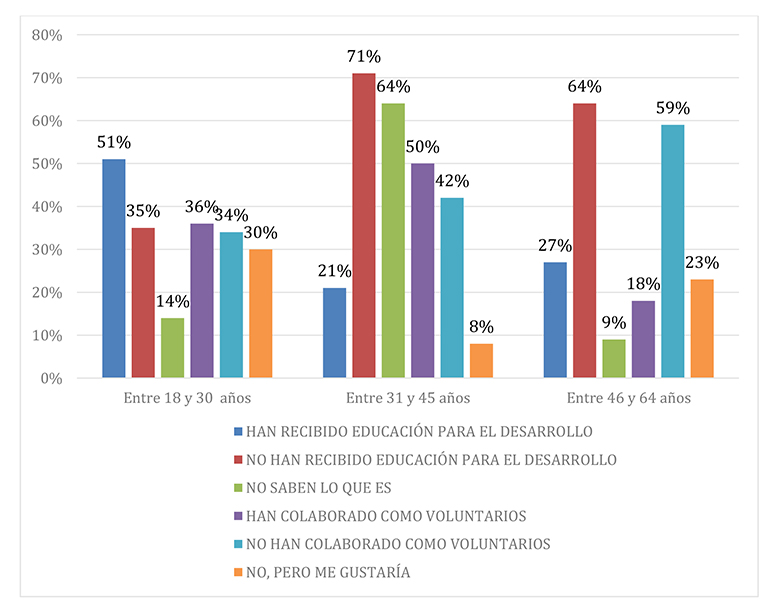

On the other side, and in relation to the answers provided by the public on this item, 45% of respondents expressed confusion when answering what the Third Sector is. In fact, only the group aged 18 to 35 years old states that they have sometime received information about some non-profit organization in Valladolid, which represents 51% of surveyed people.

In the following table, we observe the training received by age groups, which should be considered by the entities of the TS to put emphasis on volunteers. Although this is not the only mission of education for development, we check in the following table by age the percentage of population that has received this education, and the percentage of them who have ever collaborated as volunteers.

Source: Self-made

Picture 4. Education for development.

In this section, in the last age group we also added: is it necessary to receive education for development throughout life? Do the entities have to emphasize the public and young people? and have the values of solidarity changed? (Picture 4)

82% of respondents think affirmatively, that education for development has to be taught throughout life, insisting on all audiences alike, 91% of the sample thinks so.

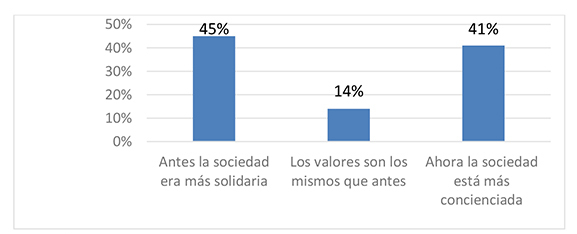

Regarding solidarity values, there is no notable trend, as we can see in the following picture, since those who think that, before, society was more supportive and those who believe that it is currently more aware (Picture 5) are very equal.

Source: Self-made

Picture 5. Changes in solidarity values.

4.2. Communication management

Communication is the backbone of our work. In this sense, we have analyzed how messages are managed abroad and whether citizens receive the contents launched by NGOs effectively.

Only 38% of the entities have a budget item intended for communication. That is, most of these organizations do not invest money in something that will help them meet their objectives.

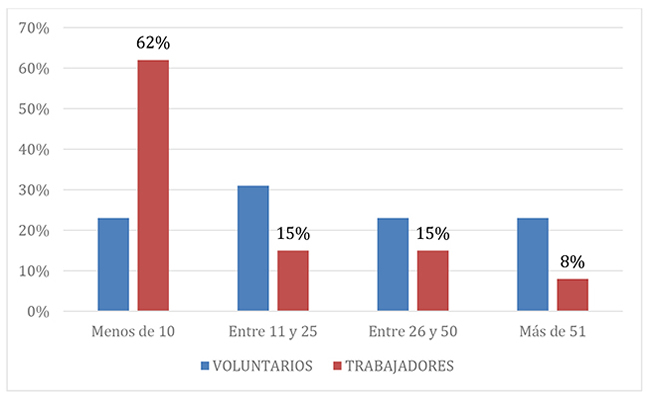

But, most of them, 62%, the majority, do have a person in charge of managing communication issues. Only 15% do not have anyone to manage it. The remaining 23% do not have a person in charge, but they affirm that these tasks are covered.

Regarding their opinion, 85% say that communication is a key element to achieve the objectives set by the entity. 92% believe that all entities in this sector have to have a Communication Department.

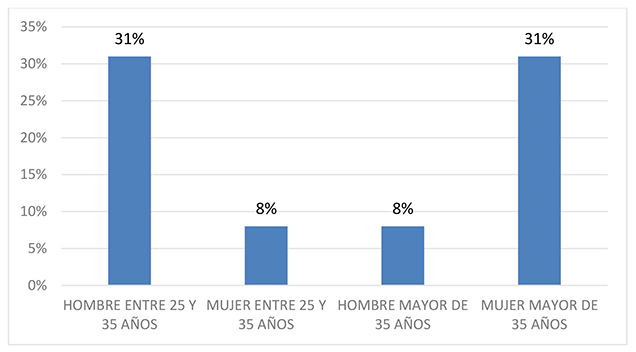

The profile of these workers is summarized as follows: men aged 25 to 35 years old and women older than 36 years, both with 31%. In Picture 6, we see the rest of the profiles (Picture 6):

Source: Self-made

Picture 6. Profile of the communication worker.

It should be noted that most of the entities, 69%,, have an internal communication plan.

Regarding the best form of communication in the city of Valladolid, a large part of these entities think that the best way is social networks and the Internet, mainly Facebook. We highlight the following answers on the optimal form of communication:

– Show the meaning of the concrete actions you carry out

– Through awareness activities

– Word of mouth

– Personal contact between recipients and collaborators and administrations

– The audiovisual

– The press

– Through signage

Taking into account the form the entities believe to be the best to reach their audience, we look at the other dimension, what society thinks about. In the first place, we present the errors they think that the organizations make by age group.

4.3. New Information Technologies

One of the points we are most interested in knowing is the scope of the use NGOs make of New Information Technologies.

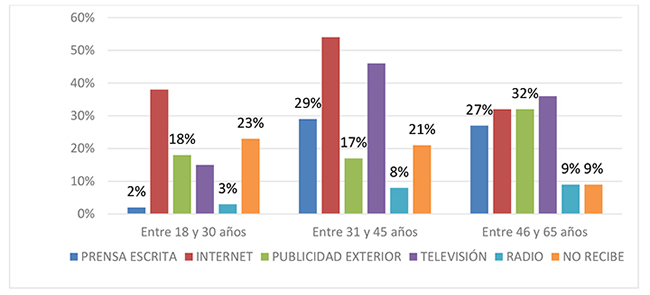

Internet is the majority way in which the society residing in Valladolid receives information about the entities of the Third Sector (Picture 7).

Source: Self-made

Picture 7. Means by which they receive information from the TS.

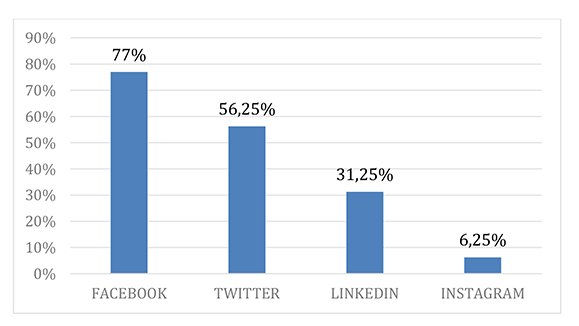

Within this medium, 77% of the entities use social networks to get closer to their audience, with Facebook being the most used and Instagram being the least used, as the picture shows.

Social networks, as we have seen previously, are one of the formulas that entities believe to be most effective in communicating their actions. We have also seen that, to them, Facebook is the best way and it is also the social network through which society follows their accounts.

According to the opinion gathered by TS entities, 92% agree that new information technologies have helped communication between organizations and their target audience. Only 8% say they strongly disagree with this statement.

For its part, the opinion of the population on social networks is similar. 90% believe that social networks help them become aware of the information provided by the entities in the sector (Picture 8).

Source: Self-made

Picture 8. Use of social networks of TS entities in Valladolid.

Management of these social networks, in 46%, is carried by a worker in the Communication Department, followed by a 15% by a volunteer or a group of volunteers from the entity. None of the surveyed organizations delegates this task to a person or company external to them.

The opinion of these workers about the social networks of the entities of the TS is that 69% believe that all should have presence in these networks to better reach their target audience, as compared to 31% who believe that they should not.

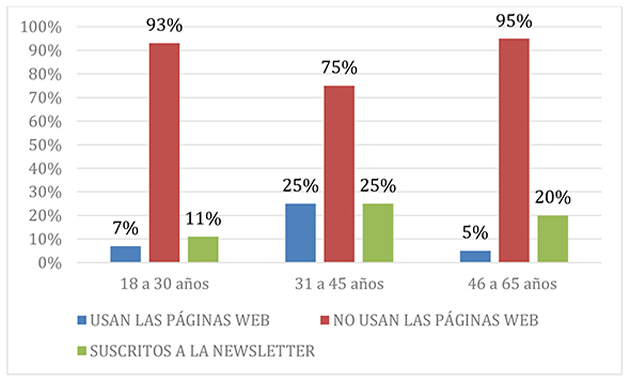

Another aspect within the use of new communication technologies, but this time from the side of society, is whether the public accesses the web pages of the local entities of the Third Sector. We start from the fact that all the entities that make up the sample have a web page (Picture 9).

The three surveyed age groups respond, with a percentage higher than 50%, that they do not use the web pages of the entities, with the population aged 31 to 45 years being those who most see them with 25%.

Among those who visualize the theme, it is different depending on the age group: while the youngest claim to consult the pages of We Can Be Heroes, the Anti-AIDS Committee of Valladolid or Umoya; the middle age group accesses the Food Bank page, mainly followed by the Red Cross and UNICEF; those over 46 years of age also consult Red Cross and UNICEF.

Source: Self-made

Picture 9. Use of the web pages of TS entities.

4.4. The impact on society

In this section, we analyze if there is really a relationship between society and the organizations of the Third Sector at the local level. For this, the first question we asked ourselves is: is the population interested in what happens in society? In all three cases, the reality is that more than 90% do show interest in everything that happens in society, they especially show interest in the most disadvantaged, a very encouraging fact when addressing this block.

The following premise refers to whether society is aware of the actions of the Third Sector. For this, first, we emphasized that the society resident in Valladolid receives less information about the entities of the TS than they would like, so the entities in this sector should intensify the information they send, but adapting it to each sector of their target

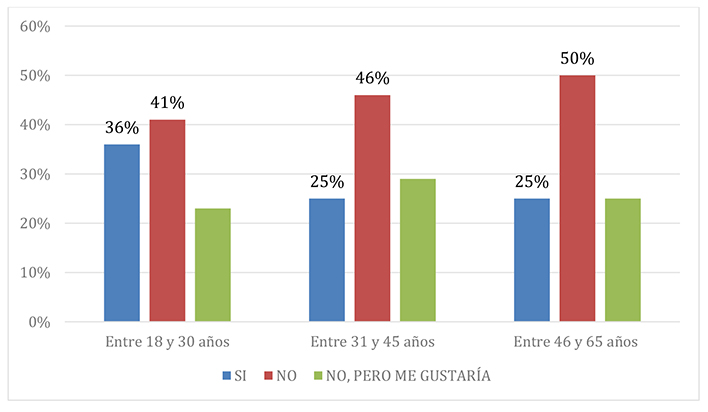

But really, does the population know what actions are carried out in the city? The answer is no, but with a significant and hopeful percentage that would like to know society. In the following Picture 10, we observe these answers divided into age.

Source: Self-made

Picture 10. Knowledge of the actions that are carried out.

In view of the results, the sector of population that has more knowledge about the actions is the age group from 18 to 30 years. On the other hand, the one that has less knowledge is the sector aged 46 to 64. Although the ones who would like to receive more information is the second age group. Therefore, the degree of awareness (greater or lesser) that society has with different social causes is related to the social reality or realities present in the different age groups of the population.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Next, we present the most relevant conclusions of the piece of research we carried out.

Regarding the main form of financing of the entities of the Third Sector of Valladolid, it is public financing. 62% of surveyed entities confirm this. Although, we can say that the contributions of the partners is the second formula these entities have, with 31%.

The entities that make up the Third Sector of Valladolid have a larger number of volunteers than contracted personnel. In addition, the surveyed workers think that this is the optimal organization for this type of entity. The Third Sector has to be supported thanks to the volunteers, but is society really willing to do so? 80% of respondents believe that we should all be volunteers at least once in our lives, but they lack enough information to become volunteers and prefer to collaborate in a timely manner.

As to whether in the analyzed entities of the third sector there is a person to manage communication, the answer is negative, since not all organizations in this sector have a person in charge of handling these issues. In most of these entities there is a worker, we can only say 62%. 15% of organizations do not have a person dedicated to management. The remaining 23% affirm that they do not have a person in charge only of communication but that this area is covered.

Therefore, if the biggest problem that society perceives when collaborating with these entities is misinformation and not all of them emphasize this issue, we find here one of the main errors of the lack of relationship between both parties.

Another analyzed aspect is the use of new technologies to reach the target public, in the case of Valladolid, associations use new technologies to reach their target, mainly social networks and as we have seen, especially Facebook. Although they also use their web pages and subscribe to the newsletter to reach their audience. But, although the entities are on the Internet to reach their target audience, the impact they get on society is not the best nor the most efficient. They would have to perform a thorough analysis to see if the conversions that are pertinent and necessary to make their work in these networks are the best and most effective, and whether they really serve to inform.

Regarding the knowledge of the actions carried out by the organizations of the Third Sector in Valladolid, the data show that the population of the city does not know the actions carried out by these organizations. And not only do they not know what actions are organized, but they also do not know how they can collaborate. Although, as a positive point, they are interested. They would like to receive more information than they receive and know what the entities are doing.

In summary, in view of the data obtained, one of the communication objectives of these organizations focuses on raising awareness in society; however, it is perceived that they only seek to raise funds. It is clear that one of the main problems with this sector is the distrust and lack of credibility that is generated many times in society. Gathering partners who provide financial help generates distrust, we often hear questions such as: does this money really come? Entities should be able to be transparent and reliable so that these doubts disappear in society. Among other things, they should provide more information about the origin and destination of the resources they manage.

In short, active communication between the entities and society is key to the good understanding of both parties and for the objectives to be met. This, together with education, a key element for society to collaborate in a more optimal way, will contribute its bit to make the world a better place.

REFERENCES

1. Almansa A (2003). Teoría, estructura y funcionamiento de los gabinetes de comunicación. El caso andaluz (tesis doctoral). Universidad de Málaga: Málaga.

2. Anuario del Tercer Sector de Acción Social en España (2016). Recuperado de http://www.luisvivesces.org/upload/95/52/2012_anuario_tsas.pdf

3. Balas M (2011). La gestión de la comunicación en el Tercer Sector. Madrid: ESIC.

4. Congdcyl (2016). Nuestras ONG. Recuperado de http://www.congdcyl.org/index.php/listado-ongd

5. Estudio sobre el presente y futuro del Tercer Sector social en un entorno de crisis. (2016). Recuperado de https://www.pwc.es/es/fundacion/assets/presente-futuro-3sector.pdf

6. Fundación Mutua Madrileña (2014). El impacto de la crisis en las ONG. Estudio sobre la situación de las entidades sin ánimo de lucro en España. Madrid: Mutua Madrileña.

7. García-Muñoz T (2003). El cuestionario como instrumento de investigación/evaluación. Recuperado de http://www.univsantana.com/sociologia/El_Cuestionario.pdf

8. García-Orosa B (2009). Gabinetes de Comunicación online. Claves para generar información corporativa en la Red. Zamora: Comunicación Social Ediciones y Publicaciones.

9. Gómez-Gil C (2005). Las ONG en España. De la apariencia a la realidad. Madrid: Los libros de la catarata.

10. González-Luis H (2006). La comunicación herramienta estratégica en la misión de las ONG´s. FISEC-Estrategias, número 5, Mesa I, 31-53. Recuperado de http://www.fisec-estrategias.com.ar

11. Granda G, Lutz M (1988). Las Organizaciones no Gubernamentales en la Cooperación para el Desarrollo. Madrid: CIDEAL.

12. Herranz-de-la-Casa JM (2006). La comunicación y la transparencia en las Organizaciones No Lucrativas (tesis doctoral). Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Recuperado de http://eprints.sim.ucm.es/11539/1/T29229.pdf

13. Información Municipal Valladolid (2016). INE. Recuperado de http://212.227.102.53/navegador_web_nuevo_aytovalladolid/fichas/1/47186.pdf

14. Junta de Castilla y León (2016). Aplicaciones de la Consejería de Presidencia. Recuperado de https://servicios1.jcyl.es/presw/facespublic/fw/inicio.jsf?_appId=waso&_flujo=%2Fwaso%2Fcu1%2FConsultaAsocTF.xml

15. Junta de Castilla y León (2016). Listado de entidades inscritas en el Registro de Agentes en la Administración Pública. Recuperado de http://www.jcyl.es/web/jcyl/AdministracionPublica/es/Plantilla100/1284418708070/

16. Marcuello C (1996). Las Organizaciones No- Gubernamentales de Desarrollo y la construcción positiva de su identidad. Acciones e Investigaciones Sociales, nº 5, 103-120.

17. Marcuello C (coord.). (2007). Capital social y Organizaciones No Lucrativas en España. El caso de las ONGD. Bilbao: Fundación BBVA.

18. Matalon R, Ghiglione B (1989). Las encuestas sociológicas teórica y práctica. México: Editorial Trillas.

19. Plan Estratégico del Tercer Sector de Acción Social. (2016). Recuperado de http://www.msssi.gob.es/ssi/familiasInfancia/ongVoluntariado/docs/Aproximacionalasituciondelamujeresyhombreseneltercersector.pdf

20. Plataforma07.org (2016). Qué es el 07. Recuperado de http://www.plataforma07.org/queesel07.html

21. Rodríguez-Cabrero G, Marbán V (2008). Visión Panorámica del Tercer Sector Social en España. Revista Española del Tercer Sector, 9. Recuperado de http://www.fundacionluisvives.org/ servicios/publicaciones/rets/index.html.

22. Ramírez T (1995). Gabinetes de comunicación. Funciones, disfunciones e incidencia. Barcelona: Bosch Casa Editorial.

23. Salamon LM, Anheier HK (1997). Defining the nonprofit sector A cross-national analysis. Institute for Policy Studies, The Johns Hopkins University.

24. Sampedro V, Jerez A, López-Rey J (2002). Imagen pública y estrategias de comunicación, en Blanco-Revilla M, (ed.) (2002). Las ONGs y la política (pp. 251-281). Madrid: Ediciones Istmo.

25. Serrano M (2001). Las ONG entre la empresa y el Estado. ¿Cambio o reproducción del sistema?,. En Nieto-Pereirea L (coord.) (2001). Cooperación para el desarrollo y ONG. Una visión crítica (pp.141-169). Madrid: Los libros de la catarata.

26. Soria MM (2011). La Comunicación en las ONG españolas: influencia de Internet en el modelo estratégico de relaciones con los públicos (tesis doctoral inédita). Universidad de Málaga: Málaga.

27. Trespalacios JA, et al. (2005). Investigación de mercados: métodos de recogida y análisis de la información para la toma de decisiones. Madrid: Paraninfo.

AUTHORS

Begoña Gómez Nieto

She holds a PhD in Information Sciences from the IE University of Segovia and a degree in Communication, Advertising and PR branch from the Complutense University of Madrid. She is currently a professor in Advertising and Public Relations, Journalism and Audiovisual Communication of the European University Miguel de Cervantes de Valladolid. He has published more than forty articles as a result of his lines of research focused on the field of corporate communication, advertising (ambient marketing, social networks, content structure on websites, written press and advertising, content differentiation, ...) and journalism , book chapters and several books.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1055-1864

María del Mar Soria Ibáñez

Degree in Journalism from the University of Malaga. PhD in Audiovisual Communication and Advertising from the University of Málaga. Teaching experience in Audiovisual Communication degree at CES Felipe II, attached to the Complutense University of Madrid. Assistant professor in Official Masters at the University of Malaga and online specialization programs. Research and teaching stays at the University of Algarve (Portugal). Professional experience in the press, radio, television, communication departments and social media manager. She is currently an adjunct professor in the UEMC and director of the Equality Unit of the same. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7972-4495

Beatriz Concejo Ulloa: She has a degree in Advertising and Public Relations from the European University Miguel de Cervantes (Valladolid). He is currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in Communication with Social Purposes: Strategies and Campaigns at the University of Valladolid. For years she has been linked to the Third Sector, she has worked at UNHCR and she has worked as a volunteer with Procomar, Proyde, Cáritas and Unicef. Works since 2014 in Seminci in the Guest and Protocol Department.