doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.141.93-114

RESEARCH

A STUDY ON WOMEN SEXUAL TRADE AND ADVERTISING. THE ROLE OF THE SPANISH PRESS

UN ESTUDIO SOBRE EL COMERCIO SEXUAL DE MUJERES Y PUBLICIDAD. EL PAPEL DE LA PRENSA ESPAÑOLA

UM ESTUDO SOBRE O COMÉRCIO SEXUAL DE MULHERES E A PUBLICIDADE. O PAPEL DA IMPRENSA ESPANHOLA

Rodrigo-Fidel Rodríguez-Borges1 Doctor of Information Sciences and Doctor of Philosophy. Professor of Philosophy in Secondary Education. He is Professor at the Department of Communication Sciences and Social Work at the University of La Laguna. He has been a member of the research team of the R + D + I “Justice, citizenship and gender: feminization of migration and human rights” (2011-2015) and he is currently a member of the research project “Justice, citizenship and vulnerability. Narratives of precariousness and intersectional approaches” of the Ministry of Science and Innovation (2015-2018). He belongs to lIUEM (University Institute of Studies on Women). He is the author of the book The discourse of fear. Immigration and press on the southern border of the European Union, published by Plaza y Valdes in 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rodrigo_Rodriguez_Borges

Esther Torrado-Martín-Palomino1 PhD in Political Science and Sociology. BA in Political Science and Sociology and Social Work. Professor - researcher at the University of Laguna, Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Member of IUEM (University Institute of Studies on Women). She has published several articles and participated in international congresses related to gender, migration, sexual exploitation. She has participated as a researcher in R & D related to migration and sexual exploitation. She is part of the consolidated research group “Gender, Citizenship and Cultures. Approaches from the feminist theory.” She is currently involved in the research projects “Justice, citizenship and vulnerability. Narratives of precariousness and intersectional approaches” of the Ministry of Science and Innovation. National Research and Gender Plan: “Generating a more inclusive and competitive knowledge economy” of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of the Government of Spain. https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=HLnoRkoAAAAJ&hl=es

1University of La Laguna. Spain

ABSTRACT

This text reflects on the role of the Spanish press in the sexual commercialization of women through contact advertising inserted in their pages, taking as a starting point a sample of 860 advertisements that appeared in the main Spanish newspapers during 2016. On the one hand, we analyze the keys of the advertising discourse of prostitution, the main features of which are the hypersexualization of the physical attributes of women, reproduction of traditional gender roles and racialization-ethnicization of the offer, which is related to intensification of migratory flows heading for to Spain. On the other hand, we present the ethical and legal debate on this kind of advertising, nonexistent in the reference European press, but widespread in the Spanish newspapers.

KEYWORDS: Contacts ads, gender, advertising, prostitution, press

RESUMEN

Este texto reflexiona sobre el papel de la prensa española en la comercialización sexual de mujeres a través de la publicidad de contactos que insertan en sus páginas, tomando como punto de partida una muestra de 860 anuncios aparecidos en los principales diarios españoles durante 2016. De una parte, se analizan las claves del discurso publicitario de la prostitución, que presenta como rasgos principales la hipersexualización de los atributos físicos de las mujeres, la reproducción de los roles tradicionales de género y la racialización-etnificación de la oferta, que se relaciona con la intensificación de los flujos migratorios dirigidos a España. De otra parte, se presenta el debate ético-jurídico sobre esta clase de publicidad, inexistente en la prensa europea de referencia, pero generalizada en los periódicos españoles.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Anuncios de contactos, género, publicidad, prostitución, prensa

RESUMO

Este texto reflexiona sobre o papel da imprensa espanhola na comercialização sexual de mulheres através da publicidade de contatos que inserem em suas paginas, tomando como ponto de partida uma mostra de 860 anúncios aparecidos nos principais jornais espanhóis durante 2016. De uma parte analisam as chaves do discurso publicitário da prostituição, que apresenta como traços principais da hiper sexualização dos atributos físicos das mulheres, a reprodução dos roles tradicionais de gênero e a racialização – etinificação da oferta, que se relaciona com a intensificação dos fluxos migratórios dirigidos à Espanha. Por outra parte, se apresenta o debate ético – jurídico sobre este tipo de publicidade, inexistente na imprensa européia de referência, mas generalizada nos jornais espanhóis.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Anúncios de contatos, gênero, Publicidade, Prostituição, Imprensa

Received: 17/03/2017

Accepted: 22/06/2017

Published: 15/12/2017

Correspondence: Rodrigo Fidel Rodríguez Borges. Rodriguez.borges@ull.es

Esther Torrado Martín-Palomino. estorra@ull.edu.es

How to cite this article

Rodríguez Borges, R. F. Torrado Martín-Palomino, E. (2017). A study on women sexual trade and advertising. The role of the Spanish press. [Un estudio sobre el comercio sexual de mujeres y publicidad. El papel de la prensa española] Vivat Academia.

Revista de Comunicación, 141, 93-114.

doi http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.141.93-114

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1061

1. INTRODUCTION

Generically, the activity of prostitution has been defined as the sale of sex for money. This starting definition must be problematized to address the complexity of a phenomenon that has multiple edges that deserve to be considered.

According to the Report on Sexual Exploitation and Prostitution and its Impact on gender equality, approved by the European Parliament’s Commission on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in January 2014, prostitution “affects around 40-42 millions of people around the world” and it works like a huge business “in which different actors are interconnected and the pimps perform calculations and act to strengthen or increase their markets and maximize profits, and sex buyers play a fundamental role, since they keep the demand of this market” (p.6-7).

Three additional features of this report should be considered in order to outline the phenomenon of prostitution. In the first place, that “the great majority of people who practice prostitution come from vulnerable groups” (page 7) and it is precisely this situation of vulnerability and poverty what opens a huge question about the possibility of considering it a freely chosen activity, especially in the case of women (de Miguel, 2015).

Secondly, and apart from the open discussion about the real or presumed differences between voluntary prostitution and forced prostitution, the Report indicates that “prostitution is a form of slavery incompatible with the dignity of the person and with their fundamental rights” and that trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation “constitutes one of the most atrocious violations of human rights” (page 6).

Third, prostitution has an obvious gender component since “the vast majority of people who prostitute themselves are women and girls and almost all users are males”. For this reason, it can be affirmed that prostitution is intrinsically linked “to gender inequality in society” and has “an effect on the social standing of women and men in society as well as on the perception of the relationships between women and men and in sexuality” (p.6-7).

This way, prostitution is, at the same time, the “cause and consequence of gender inequality”, it perpetuates “gender stereotypes and stereotyped thinking about women who sell sex” and feeds “the idea that the body of women underage Women is for sale to meet the male demand for sex” (p.10). From evidences like these, authors like RW. Connell (2003) consider prostitution to be an institution at the service of sustaining the gender order and traditional masculinity, extracting from it a masculine symbolic capital, a gender surplus value as compared to women.

Far from being a business in regression or stabilized by government policies that seek to keep it under control, prostitution is now a growing business - says the Report (p. 7) - due to “the serious relationship existing between procuring and the organized crime”. The growth of inequalities, the poverty suffered by many areas of the planet, the negative effects of economic globalization and the persistence of patriarchal structures contribute to the growth of a phenomenon, which in recent years has received the additional boost of new information and communication technologies (Ballester, 2014; Weber and Jaimes, 2011). Indeed, the Internet and social networks have a growing role in attracting new and young prostitutes through human trafficking networks and prevention actions and campaigns are necessary, taking into account the most vulnerable targets (Report, p. 12).

In the case of Spain, to this set of general characteristics we must add a peculiarity of legal order: prostitution is an allegal activity, but it can be legally advertised. It is precisely this situation of allegality - neither legal nor illegal - what makes it difficult to establish a reliable estimate of its benefits, nor of the number of women involved in this sex trade in our country. The agreement of the European Union in 2014 to incorporate into the accounting of the GDP of each country illicit activities (prostitution, drug trafficking, tobacco smuggling and illegal gambling) has led the National Statistics Institute (INE) to calculate that in Spain there are some 600,000 prostitutes that 6% of the population uses and around which a business that generates around 3,672 million euros a year is generated (1). These numbers of prostituted women represent a remarkable growth in comparison with the data collected in the Report of the Paper on Prostitution, approved by the Spanish Parliament in March 2007, which mentioned the existence of some 400,000 prostitutes and 15 million potential male clients. , who spent 50 million euros daily in this respect. In this huge business, advertising of “contacts” in the press come into play, which, in addition to advertising prostitution itself, favor the reproduction of stereotypes and attitudes that come to be perceived as a standard by society (CAA, 2016; García del Castillo et al, 2009; Bernstein, 2001). This image of social normality that the media contributes to consolidate reinforces the interest of analyzing the content of the advertisements that appear daily on the pages of newspapers.

(1) Véase la información aparecida en el digital VozPópuli, [en línea], disponible en: http://vozpopuli.com/economia-y-finanzas/50045-los-espanoles-que-recurren-a-la-prostitucion-gastan-127-5-euros-al-mes-radiografia-oficial-del-negocio, recuperado: 15 de enero de 2017.

Starting, let us say that most Spanish newspapers defend the existence of this type of advertising, appealing not only to their economic importance for the sustainability of companies but also to freedom of expression. As we will see later, to these arguments, the press adds a third party that is not easily overlooked: as a matter of elementary logic, they argue, before banning advertising of prostitution, one should proceed to outlaw prostitution itself. Apart from the debate on the legal status of prostitution, another angle of the discussion, ethical or moral, should lead us to ask ourselves whether this activity and advertising accompanying it is acceptable in advanced democratic societies, as they are a violation of the human rights, as the Report of the European Parliament considers. The decision of the Swedish authorities to classify the purchase of sexual services as a crime, embodied in the 1999 law, is encouraged precisely by the ethical conviction that the purchase with money of the sexual use of a woman’s body is unacceptable (Engman, 2007).

The debate, both in its legal and moral aspects, is far from being settled and the debate on whether prostitution can be considered a form of freedom of expression and action or, on the contrary, it is a violation of the equality rights of women, given that in the vast majority of occasions the advertised product is the sale of the women’s body, remains open, even within the feminist movement itself. Thus, when faced with those who defend the open legalization of prostitution and equate it to a job like any other, those who oppose this solution reject that prostitution can be considered a free option when material conditions rule out 99% of the other options (MacKinnon, 2010) and propose, therefore, to advance in the establishment of public policies for its abolition, protecting women, curbing new recruitments and dissuading demand. In short: it would be about ending an activity that they describe as an authentic “school of human inequality” (de Miguel, 2015). Regardless of the future course of this debate, the truth is that in Spain, to date, open advertising of prostitution and the impunity of buyers or applicants for these services have contributed to the standardization of the phenomenon, which is seen with widespread indifference by a good part of society, despite the denunciations of feminist movements.

2. A LOOK AT THE SPANISH NEWSPAPER: A PIMP PRESS?

The affirmation, with an evident provocative intention, was pronounced by journalist Arsenio Escolar, director of 20 Minutos, during the XVI Congress on Digital Journalism held in Huesca (Spain) in 2015. Escolar has been especially combative with that press that improves its profit account with the sale of prostitution ads:

In their noble pages they continue to defend the rights of women and the dignity of women, and a few pages later there are hundreds of small well paid ads behind which there is sexual exploitation, trafficking, mafias, extortion ... Says the dictionary of the Royal Academy that a pimp is one who obtains benefits from the prostitution of another person. Please: no more pimp press (Escolar, 2015).

Certainly, advertising of prostitution in the Spanish press has a history of more than 3 decades and is maintained today in most national and regional capitals, which share this business niche as well as the marketing tools and logics for its dissemination and sale. In Spanish newspapers, offers of this nature, inserted in the classified section or word ads, coexist without problems with news that inform readers of initiatives against prostitution or statements against women trafficking.

For example, in July 2016 the newspaper La Vanguardia inserted in its pages the news that the local police of Valencia (Spain) had fined several taxi drivers in the city for advertising prostitution (2).

(2) Véase: http://www.lavanguardia.com/local/valencia/20160718/403298528962/policia-local-valencia-taxistas-publicidad-sexista.html.

The reason for the sanction was “to offer a degrading image of women” by displaying images of prostitution premises on the side of their vehicles, as well as making brochures and cards available to customers. In those days, that same newspaper - the third among the general information press with almost 600,000 daily readers (EGM, 2016, 8) – inserted, in the classified ads section of its printed edition, claims like these:

– Morbid, I suck it.

– Russian. I’m not shaved! 28 years. Submissive

– Marta, Dominican, 21 years old. Full. French kisses. Fleshy lips Sweet mouth

– 12 young and beautiful oriental women. From 20 to 25. All services. 24 hours

La Vanguardia is not, however, the exception but the standard in the quality press that is published in Spain, unlike most major European newspapers (Le Figaro, Libération, La Repubblica, The Guardian or the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) that reject this type of advertising. The main Spanish newspapers, on the contrary, are fed daily with this type of income, through advertising insertions that abound in expressions of this sort: “Cuban shaved pussy, bareback blowjob,” “Compliant Asian, I do everything, French until the end”, “Pregnant Brazilian, mulatto, restless ass, fuck it”, etc. The justification for maintaining this line of business is obviously economic, since the income this advertising provides to newspapers is not negligible. The Report of the Paper on Prostitution indicated on page 48:

The media also derive benefits from the prostitution business. The press of our country obtains important income from prostitution advertising. The editions of the four main generalist newspapers of our country in a working day collect a considerable number of advertisements (El País, 702, El Mundo 672, ABC 225 and 91 La Razón). The newspaper with more circulation in this country [El País] takes around 5 five million euros per year.

With good reason, the managers of the Pearson publishing group - publisher, among others, of The Economist and The Financial Times - have expressed their surprise “in view of the fact that Spain is one of the only European countries where almost all the quality press publishes this type of ads in exchange for large sums of money” (3). The conclusion seems obvious: in Spain, prostitution advertising has been for years a widely accepted activity, despite plans of action, more or less decided, such as the one that the Ministry of the Interior launched in February 2015 under the name With trafficking there is no deal. The plan aimed to reduce the numbers related to prostitution, putting under “unbearable pressure” the customers who feed a business, which, according to the ministry, has its most numerous victims in women who come from Eastern Europe, Colombia, Brazil, Paraguay and Nigeria, in addition to the Spanish ones. With trafficking there is no deal, it announced two novel initiatives. On the one hand, the inclusion of emerging messages against prostitution that would appear when a potential client sought sexual contacts on the Internet; and, on the other hand, the placement of those dissuasive messages on the pages of contact announcements of the written press. None of these initiatives has materialized. Also in July 2016, another fact related to prostitution and its advertising came to focus on the conduct of the Spanish press: during the celebration of the Sanfermines of Pamplona, the association Action Against Trafficking (ACT) appeared before the public opinion to denounce that, during the festivities, the pimps had in the city more than 100 floors to prostitute women, in addition to premises and clubs. The Association also pointed to the press as an indirect beneficiary of this business, thanks to the multiplication of its income with the contact ads published on its pages (4).

(3) The opinion of the Pearson Group appears in the document of the Spanish Council of State Report on the possibilities of action against advertisements of sexual content and prostitution published daily in various press media, p.3.

(4) See information published in the newspaper El Español: http://www.elespanol.com/espana/20160708/138486654_0.html.

Apart from these two particularly noted examples, advertisements for prostitution have a cross-sectional presence in most Spanish newspapers, without their scope of circulation -regional or national- or the orientation of their editorial line indicating substantial differences. See this selection of examples drawn from the national and regional headings that have been part of the sample analyzed in this piece of research:

– “Alexia, bareback French, fucked my little ass, grind my mouth” (El Correo, 10/27/2016).

– “I suck it greatly, come wherever you want” (El Periódico, 10/07/2016)

– “Authentic Jamaican, French drunk, fuck my ass on all fours” (El Correo, 10/27/2016).

– “Come on, fuck me, I get it in a miniskirt, no panties” (El Día, 09/30/2016).

– “Susy, black, deep Greek, natural French postures” (Diario de Sevilla, 10/27/2016).

– “Elena, awesome Cuban, cannon, deep throat, Greek” (El Mundo, 10/25/2016).

– “Alejandra, Puerto Rican, busty, kissing, bisexual, anal, French” (El País, 09/07/2016).

– “20 euros, I like the taste of semen, mulatto” (El Día, 09/30/2016).

– “5 girls without panties, Greek, golden rain, anal-testicular massage with fingers and more” (La Vanguardia, 07/09/2016).

– “Crystal, novelty, superliar, complete French, Greek, come wherever you want, call me” (La Provincia, 07/29/2016).

Different international pieces of research have proven that advertising of prostitution in its different media (press, television, internet, static advertising, etc.) is frequently connected to human trafficking for the purpose of social exploitation. Thus, the statement contained in the Report on Sexual Exploitation and Prostitution and its impact on gender equality, of the aforementioned European Parliament states that there is a clear relationship “between procuring and organized crime” and draws attention “to the fact that advertising sexual services in newspapers and social media can be a way to support human trafficking and prostitution” (pp. 7 and 12). In this line, the study Reading between the Lines. Examining the links between advertisements for sexual services and trafficking for sexual exploitation, focused on part of the British press and carried out by Voolma, H. and Trujillo, M. (2012), considers that press editors could be required to make sure that the sexual content ads they accept are not related to human trafficking activities (Voolma and Trujillo, 2012, 3). Since, obviously, this level of verification is beyond what newspaper editors can do, Voolma and Trujillo conclude that “the most reliable way to ensure that local newspapers are not accomplices of sex trafficking (...) is to eliminate advertisements of sexual services from their heads “(Voolma and Trujillo, 2012, 17). From a similar perspective, the Red Par (Journalists from Argentina in Network-For a non-sexist communication), aware of the connection between advertising and trafficking, categorically states in its Decalogue for the journalistic approach to trafficking and sexual exploitation: “We oppose, without concessions, any form of advertising of offer and / or demand for sex, which we believe should be prevented and eventually sanctioned” (Red Par, 2012, 24); and in the same sense, Castellanos and Ranea (2013, 129). However, it must be said that, in Spain, some publishers and media have decided to abolish the advertisements for prostitution, such as the cases of Público, Avui, El Gratuito, 20 Minutos and La Razón, which did it after the agreement signed with the Vatican to distribute the Spanish edition of L’Osservatore Romano.

3. PROSTITUTION, LEGAL STANDARD AND POLITICAL ACTION

In May 2011, the Council of Europe - of which Spain is a member - approved the so-called Istanbul Convention on the prevention and fight against violence against women and domestic violence, which, in article 14, invited the media to promote principles such as equality between women and men, non-stereotyped roles of gender, mutual respect and non-violent solution of conflicts in interpersonal relationships. The signatory countries committed themselves to encourage the media “to participate in the development and implementation of policies, as well as to establish guidelines and self-regulating standards to prevent violence against women and strengthen respect for their dignity,” while, at the same time, they would try to foster in children the capacities to “cope with an environment of information and communication technologies that gives access to degrading content of a sexual or violent nature that may be harmful” (Article 17). In the area of Spanish law and regardless of the mentions appearing in articles 14, 18 and 20 of the Constitution of 1978, we have a reference in General Law 34/1988 on advertising which, already in its original draft, considered illicit advertising to be “advertising that threatens the dignity of the person or violates the values and rights recognized in the Constitution, especially in regard to childhood, youth and women”; and that as a result of the approval of the Organic Law 1/2004 as of December 28, on Measures of Integral Protection against the Violence of Gender, specified what it should be considered illicit publicity:

The announcements presenting women in a vexatious or discriminatory way, either using their body or parts of it directly as a mere object detached from the product that is intended to be promoted, or their image associated with stereotyped behaviors that violate the foundations of our legal order, to generate the violence referred to in Organic Law 1/2004 as of December 28, on Comprehensive Protection Measures against Gender Violence (Article 3a).

Exactly that organic law on Measures of Integral Protection against the Violence of Gender indicates in its Presentation of reasons: “In the field of advertising, this one will have to respect the dignity of women and their right to a non-stereotyped, nor discriminatory image, whether it is exhibited in public or private media.” Likewise, it is established that Public Administrations will pay special attention to “the eradication of behaviors favoring situations of inequality of women in all media of social communication” (Article 13). This tour of the Spanish regulations would not be complete without mentioning a final reference, Organic Law 3/2007, for Effective Equality between Men and Women, which, in article 39, provides that:

Public administrations will promote the adoption by the media of self-regulating agreements that contribute to compliance with the legislation on equality between women and men, including the activities of sales and advertising that take place there.

Given this legal background, it is understood that the State Council, in the Report on the possibilities of action against advertisements with a sexual and prostitution content published daily in various press media, concludes:

The prohibition of advertising of ads constitutes a legitimate aim and the means used, the interdiction, is rational, reasonable and proportionate. Therefore, it can be concluded from all of the above that it is in accordance with the Spanish law that measures should be taken that contribute to limiting the publication of advertisements for prostitution “(p. 51-52).

What explanation is there, then, for the persistence of this kind of ads that could be classified as illicit advertising? Several elements operate in this matter: on the one hand, and as in other countries, in Spain the prostitution business benefits from a process of social standardization - in the final analysis, it is the “oldest trade in the world” - which makes the domination and violence undergone by prostituted women invisible. On the other hand, press editors are not willing to give up a millionaire business and have been clearly opposed to any attempt to move in the way of banning the ads, arguing that it would be a contradiction to declare advertising illegal and not to ban activity advertised as illegal. The position of the Spanish daily press was clearly evident in 2010, when the attempt of Minister Bibiana Aido to agree with the press on the elimination of this type of advertising was answered by El Mundo -the second Spanish newspaper in importance- with an editorial in which freedom of expression and business was raised: one must “let each newspaper do what it considers appropriate with the advertising of contacts. Unless, like the extreme right, the minister advocates penalizing prostitution “(El Mundo newspaper, 2010).

There is also another explanatory element that must not be overlooked: regardless of its ideological orientation, lack of determination of the political parties to end these ads has also to do with the fear of facing the wear and tear entailed by having the majority of the press against that. That was, at least, the opinion of the deputy of the Basque group Joseba Agirretxea, expressed in the parliamentary seat: “the only thing that is done is to say things, to make declarations of intentions, to be very well in a Commission and later, when one has to face powers such as, for example, the media, which have a lot of power and a lot of money, is when their legs tremble ” (5).

(5) Diario de sesiones del Congreso de los Diputados, p. 34. Recuperado: http://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L10/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-10-CO-469.PDF.

When, in 2010, they ran aground on attempts to get the newspapers to eliminate the motu proprio ads and the socialist government seemed determined to ban them by law, the Association of Spanish Newspaper Publishers (which groups the main newspapers) made public a statement in which it flatly rejected “any kind of advertising restriction” because “it would violate the fundamental rights recognized in the Constitution referring to freedom of expression and the right to information” (newspaper El Periódico, 2016). It explains, then, the impotence that transpires in the recent study Sexist stereotypes through advertising in the Mediterranean space, driven by the Network of Regulatory Institutions of the Mediterranean (RIRM):

Stereotypes reproduce attitudes and opinions perceived as the standard by society, where gender equality is far from being a reality. In most of the countries, their transmission through the media and advertising cannot be fought judicially or sanctioned by the regulatory and self-regulatory bodies, except in very serious cases of violation of the dignity of woman (CAA, 2016, p. 2).

4. ANALYSIS OF THE ADVERTISING DISCOURSE OF CONTACT ADVERTISEMENTS IN THE SPANISH PRESS

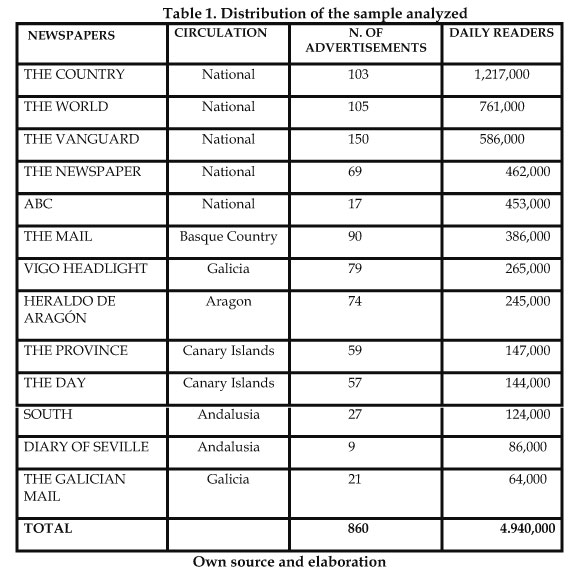

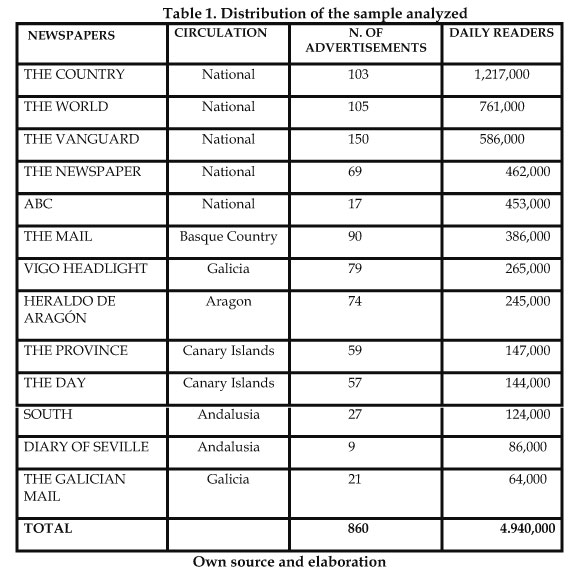

The analysis of the content of the contact advertisements in the Spanish press starts from a random sample consisting of 860 advertisements, which appeared in the “Classified” section of 13 Spanish general information newspapers in the months of September, October and November. 2016. Out of the selected newspapers, five are of national circulation and the remaining eight are distributed in different autonomous communities (Catalonia, Basque Country, Galicia, Canary Islands, Andalusia and Aragon). These 13 newspaper headlines together bring together almost five million readers (4,490,000, according to the General Media Study from February to November 2016), which represents 47% of Spanish press readers; a figure that gives an idea of the scope and visibility of this form of advertising. Table 1 summarizes the basic data of the sample.

In the studied sample, three nationally distributed newspapers -La Vanguardia, El Mundo and El País- are the ones that insert a greater number of contact advertisements on their pages; while, out of those of regional circulation, El Correo, País Vasco and Heraldo de Aragón are the ones with a highest number of advertisements. Beyond the counting of advertisements, the focus of research has been centered on the qualitative analysis of the discourse and the selling strategies of the “product” that are observed in this type of advertising messages. Indeed, the advertising discourse, its content and the way of expressing it, help to illuminate the nature of the phenomenon of prostitution and the relationships that women and men have in and through it. From the analysis of the content of this type of publicity, a set of common features emerge, such as:

A business of gender: In the set of 13 analyzed newspapers and in each of them separately, women make up the vast majority of the “offer” of advertised prostitution, well above people who identify themselves as transvestites or transsexuals and males. Thus, of the ads that identify the sex of the advertiser, women account for 77%, while those of transvestites and transsexuals do not exceed 6.6% and those of men barely reach 2%; the remaining 14.4% corresponds to insertions in which the gender of the offerer is not identified.

These figures give the reason to the affirmation contained in the Report of the European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, cited above, that the vast majority of people who prostitute themselves are women and girls and almost all of requesters are men. These data are also consistent with those in the 2016 European Commission Report on the progress made in the fight against human trafficking, which states that 95% of victims of trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation are women and girls. It seems reasonable, then, to agree that any treatment of prostitution and its advertising must not lose sight of its status as a gender-marked phenomenon.

Hypersexualization: Hypersexualization or the obsession to emphasize sexual attributes is part of the social normativity in relation to women. The media, the fashion industry and women’s magazines, among other agents, contribute in a specially connoted way to feed a kind of tyranny on the female body, which does not escape adolescents or girls, who suffer a process of early erotization (Orbach, 2010). This sexual emphasis greatly affects women who advertise in the contact pages of the press, who are forced to exacerbate their sexual attributes to assert themselves in a highly competitive market, as evidenced by the fact that 39% of Spaniards aged 35 to 55 recognize having resorted to prostitution (6). Cobo (2015, 14) has made reference to this phenomenon of hypersexualization or overload of sexuality to which women are compelled:

(6) Véase la información de Europa Press: http://www.europapress.es/sociedad/noticia-39-hombres-espanoles-consumen-prostitucion-20111026162821.html

In recent decades, the media are moving inexorably in producing hyper-sexualized images of women. The dominant image of female sexuality that is been redrafted shows women as bodies (...) There is a strong regulatory pressure for women to make their body and their sexuality the center of their vital existence. This pressure is evident in the culture of exaltation of sexuality as well as in pornography and prostitution.

In the analysis, we have seen how clearly this hypersexualization of attributes and physical characteristics of women is manifested, offering a vast catalog of features to meet all customer profiles, even the seemingly less predictable:

– “Young lady, busty, thin, clear eyes”, Heraldo de Aragon.

– “Alma, 20 years, 130 breasts,” El Periódico.

– “Awesome Cuban, cannon, big ass, deep throat”, El País.

– “Mature, plump, big boobs, hairy pussy”, El Correo Gallego.

– “Brazilian, big ass, busty, kissing very much “ La Vanguardia.

– “19, good ass, 90 breasts, hot body, brunette,” La Provincia.

– “Mery, plump, mature, brunette,” El Día.

– “Mexican, brunette, thin, pert ass,” ABC.

– “Fatty, kissing very much”, El País.

Women’s offering body thus becomes a reified and fragmenting device, which is advertised by accentuating the appeal of an organ, a limb, a piece or portion “big breasts”, “natural tits”, “hairy pussy” , “wide hips”, “little breasts”, “150 breasts”, “hard ass”, “deep throat”, “white skin” or “insatiable mouth.”

Reproduction of traditional stereotypes: In addition to exaggeration of the sexual attributes, the advertised women frequently appear associated with behaviors historically attributed to traditional gender roles, manifestation of a sexual contract that has its extreme poles in the traditional marriage, on the one hand, and prostitution, on the other hand (Pateman, 1995). Thus, in addition to the explicit violence that is the phenomenon of prostitution itself, these women are also victims of other ideological forms of violence such as negative stereotyping, which functions as legitimating and activating abuse. Regarding this matter, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (OHCHR), in its general recommendations to fight violence against women, calls to remove “Traditional attitudes by which women are regarded as subordinate or they are attributed stereotyped roles that perpetuate widespread practices involving violence or coercion”. In this sample, the offered women are described either as “discrete”, “sensitive”, “submissive” and “compliant” or, at the other end of the polarity, as “vicious”, “nymphomaniac “” sluts, “” morbid “,”insatiable”. This way, the traditional stereotypes of women are reconverted into advertising-industry-serving techniques. Within the conventional stereotype of women, we can point out these examples:

– “Married Miss, utmost discretion, quite special,” Faro de Vigo.

– “Young student, Spanish. Very compliant! “Sur.

– “Shy, discreet, natural and very compliant housewife” El Correo.

– “Valeria, perfect, discreet, loving woman,” La Provincia.

– “Married girl in financial straits”, El Correo Gallego.

– “Young, beautiful, superpleasant lady, seriousness, discreet apartment,” the day.

– While, as exemplifications of the “vicious” women, we have:

– “Latino. Tatiana. youngster, vicious, nymphomaniac, perverted, “Faro de Vigo.

– “Sado, fetishism, transvestitism, coprophilia” La Vanguardia.

– “Brazilian, mulatto, pretty, hot body, big ass, vicious” South.

– “Big ass, duplex big hips. Yes to all” El Periódico.

– “Mature nymphomaniac,” ABC.

– “New, blonde, multiorgasmic” Faro de Vigo.

Between the prudish and conventional woman and the “bad” woman, there is barely room for the enunciation of some other equally stereotyped role such as Lolita, the youthful incarnation of youthful evil, the dominant mistress or the unsatisfied mature woman, equally reductive and cartoonish forms that are presumably expressions of the feminine personality: “Lolitas, 100% morbid, French sin, Greek, vibrators, kisses and more” (La Vanguardia), “Linda, 19, inexpert” (Heraldo de Aragón), “Youngster, I start, French kiss “(El Periodico),” Dutch, natural blonde, sexy love “(South),”Horny granny, affectionate, kissing very much, compliant “(La Provincia).

Racialization-ethnification: This huge sex market also serves the interest aroused by the designation of origin of the offered product: “Basque”, “Canary”, “Galician” and so on until reaching 12 autonomous communities or Spanish provinces, as well as those who simply advertised as “Spanish”. But even more striking is the heavy presence of women from other countries, identified by their original nationality (Brazilian, Romanian, Cuban, Japanese, etc.) or their ethnicity (black, mulatto, Asian, Eastern). Data extracted from the advertising inserts make mention of women of 30 different nationalities, out of which 11 are European, 16 Latin American, 3 Asian and 2 African. We can say, then, that racialization-ethnification is clearly one of the defining features of the offer of prostitution advertised in the Spanish press, with no significant difference between the national newspapers and regional or local papers. In this regard, Cobo (2016, 2) indicates that the observation of prostitution from an ethnic-racial perspective emphasizes “racism in the behavior of the male requesters, but also racial and cultural composition of women in the industry of prostitution.” In other words: a globalized phenomenon such as prostitution leads by its very nature to a market also internationalized in which “customers” demand and obtain access to an offer in which the exoticism of the available women is listed as added value. Racialization-ethnicization of supply leads to another relevant feature resulting from the analysis:

Migration and vulnerability: The connection between prostitution and migration seen in advertising prostitution in Spanish newspapers has been studied on a global scale by Saskia Sassen: “prostitution and migration deriving from finding employment are growing in importance as ways of living. Illegal trafficking of workers and especially women and children for the sex industry is growing in importance as ways of obtaining income “(Sassen, 2003, 44). As with the overall numbers of prostitution, quantifying the number of immigrant prostituted women is difficult because the lawlessness of prostitution joins the situation of irregularity found in many of these people in our country, which, incidentally, does nothing but redouble their vulnerability. In any case, the data offered by official sources credit that the increase in migratory flows to our country in recent years has led to a considerable increase in foreign prostituted women.

The report Supporting the Victims of Trafficking by Government Office for Gender Violence (Meneses et al, 2016, p. 179.), Identifies the main geographical areas of origin of immigrant prostituted women, “we can say that these women and girls come from three main geographical areas: Eastern Europe with a preponderance of women from Romania; Sub-Saharan Africa, with a predominance of women from Nigeria, and Central and South America, with most women coming from Brazil, the Dominican Republic and Paraguay”; to which we should add, continues the Report, a segment of women from the Asian continent the quantification of which is particularly difficult. The effect of migration on the composition of the group of women engaged in prostitution in Spain had already been noted in the Report on the Paper on Prostitution:

In just a few years, the number of national women engaged in prostitution has significantly decreased and they are now mostly foreign (the ratio of 90% domestic-10% foreign has been inverted in a short time, according to the Civil Guard) and although there are differences in different areas of our geography, the places of origin are, from largest to smallest, the Eastern, Latin American and Central African countries (p. 18).

These data coincide with those handled by the Civil Guard in its Report on Human Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation, which indicated that more than 90% of women engaged in prostitution in road clubs are foreigners coming from the American continent (especially Brazilian and Colombian), another 30% are European (from Eastern European countries, especially Romania and Russia) and the rest are African (mainly Moroccans and Nigerians) (in Castellanos and Ranea, 2013, p. 48).

Sexual practices: A detailed review of the content of these advertising pages confronts us with a huge catalog of sexual practices, designed to meet the needs of male customers getting,, thanks to money and price, to dehumanize women, “something they would otherwise not get unless through violence “(Szil, 2007). In that vast repertoire of practices, there are some risky behaviors such as those contained in these two ads published in Faro de Vigo: “Most vicious, I like everything without a condom, 40 years” and “18-19 years old, French without a condom”. Reification and fragmentation of the body that we discussed earlier has its “logical” translation into the pricing of the services offered. Thus, we can see it in these examples:

– “Only natural French, 20 euros. With penetration, 30 euros “, La Provincia.

– “Profound Greek, French, 30 euros”, El País.

– “Kisses, French, Greek, rain, 30 euros”, El Correo.

– “Economic French young girls”, Heraldo de Aragon.

– “20 euros, I like the taste of semen, mulatto,” the day.

– “Full French, 30 euros”, El Periódico.

– “For 20 euros, mature, natural French”, El Correo.

– “French 20 euros. full service from 30 euros on, La Provincia.

Besides being forced to conform to the requirements of customers, the dynamics of the economy of prostitution forces the women immersed in it to accept the demands of what has been called limitless “sexual neoliberalism” (de Miguel, 2015 ): availability to meet almost any requirement for a few euros, without timetables and without restrictions. Thus, we have found ads such as the following:

– “For 20 euros, mature, natural French, unforgettable pleasure”, El Correo.

– “Duplex, 2 girls, the two for one hour and two services, 60 euros. One girl half an hour and one service, 30 euros”, La Vanguardia.

– “Oriental girls, full service, departures 24 hours,” Diario de Sevilla.

– “Latin Girls: 30 minutes, 40 euros. One hour, 60 euros “, El Periódico.

– “Japanese girl, gorgeous, horny, all services”. The province.

– “For the retired and the unemployed, 30 euros 30 minutes, penetration, French”, El Correo.

– “The most morbid women will give you everything, 24 hours,” El País.

– “Vigo girls, day and night departures” Faro de Vigo.

And with the added attraction of the permanent renewal of the available women: “Spanish and international girls, youngsters, weekly news” (Heraldo de Aragón), “New luxury escorts” (La Vanguardia), “New, Elena, beautiful, chiromassage practitioner, sensual “(El Mundo),”New Asians “(El País),” New Asians, young girls, all kinds of services “(Diario de Sevilla), “New friends, girls, beautiful, affectionate” (El Día).

Recruiters: A key element in the business of prostitution is the role played by pimps. The European Parliament Report states that 90% of prostituted people depend on a pimp; thence it considers standardizing their activities to reconvert them into simple “businessmen” to be counterproductive:

Decriminalizing the sex industry in general and legalizing pimping is not the solution to protect women and underage women from violence and exploitation but, instead, it produces the opposite effect and increases the risk of suffering a higher level of violence while the growth of prostitution markets is encouraged and therefore the number of women and underage women victims of abuse increases (Report, p. 13).

The recruitment of women to introduce them into the circuit of prostitution is part of the content of the advertisements inserted into the contact sections. The presence of these requests is large, so much so that these ads are sometimes grouped together in a mini-section, as in the case of Faro de Vigo and La Vanguardia, which, under the headline Demands, includes in a single day up to 13 ads asking for women. See some selected examples:

– “Seeking ladies aged 22 to 30, blonde, different shifts,” La Vanguardia.

– “Seeking good-looking girls, job guaranteed,” Faro de Vigo.

– “Contact house requests young ladies aged 18 to 40. High income “El Día.

– “I need ladies. Fixed income, “El Mundo.

– “We need young ladies,” ABC.

– “We need young ladies, young and mature, for apartment in Bilbao” El Correo.

In summary, analysis of the advertising discourse on prostitution in the Spanish press talks about a phenomenon of gender, because the vast majority of offers is made up of women, many of them being foreign and presumably affected by situations of extreme vulnerability. Hypersexualization of physical attributes and reproduction of traditional gender stereotypes make up a significant part of the strategies of advertising the offer of prostituted women. In addition, in recent years and as a perverse consequence of globalization, ethnicization or racialization of supply has been incorporated as another feature, and maybe it is the defining trait, of prostitution ads appearing in the Spanish press. The search of exoticism as an element of attraction for customers and the need to constantly renew the supply of women have made it possible for certain ethnic and racial profiles of women to have come to replace the Spanish women in this penultimate stage of sexual exploitation. Encouraged by exorbitant business figures - 186,000 million dollars annually worldwide (European Parliament Report, 2014: 17) - recruiters regularly make use of the press to attract women to feed their business.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Prostitution and advertising it are phenomena that in recent years have undergone a profound transformation. Globalization and international migration have contributed to this change, turning sex in an internationalized and highly lucrative business for suppliers and, as we have indicated, the Spanish press is an indirect beneficiary.

The Report of the Paper on Prostitution urged the Government to “promote awareness-raising campaigns aimed at changing the social and men’s perception about women, focusing on changing gender roles” (p. 25). In that respect, it is not possible to post significant achievements, especially considering that some studies suggest that about 20% of the Spanish male population pays for sexual services (Meneses, 2016, 180). The same report also included among its recommendations “ask the media, within the framework of their deontological codes of ethics, to consider renouncing advertising related to the sex trade to prevent mafia organizations involved in sex trade from doing business” (p . 25). Appeals to self-regulation of the media also appear explicitly formulated in both Istanbul Convention and Organic Law 3/2007 for Effective Equality between Men and Women, but advances in the field of self-regulation are very poorly significant, unlike what happened to many of their European colleagues.

For now, the appeal to the moral responsibility of the press has had very limited success and only a few headers have removed this kind of advertising. Neither the Association for Self-regulation of Commercial Communication (Self-control) -which brings together major advertisers, agencies and media- has declared itself on this type of advertising, despite its deontological rules state: “Advertising shall not suggest any discriminatory circumstances whether of discrimination based on race, nationality, religion, sex or sexual orientation, nor shall it attempt on the dignity of the person. In particular, those ads that may be vexatious or discriminatory for women” (Basic Principle 10) shall be avoided. Similarly, it is striking that such a relevant initiative in many aspects like ethics and the deontological and self-regulatory code for non-sexist advertising and communication in Euskadi, signed in February 2016 by 51 media and advertising agencies, does not include any reference to sexual-content advertising, although it includes the commitment to work for equality between women and men, the elimination of violence against women and the disappearance of stereotypes. We must also say that one of the signatories of the Code was the newspaper El Correo, the contact ads of which are among those discussed in these pages.

If the path of self-regulation does not yield the expected results, our view is that it should explore the possibility of legal prohibition, a perfectly plausible possibility as noted by the State Council and, in the opinion of Torres (2012), although it could affect the right to freedom of expression, it would not involve “regulation of its essential or substantive aspects” [8]. The appeals to the free market and freedom of expression newspaper publishers resort to do not absolve them of their deontological responsibility for getting profit from advertising that denigrates women in general and, especially, immigrant women, whose extreme vulnerability makes them easy victims of sexual exploitation. Regardless of the route the possibility of a legal prohibition may have, the fact is that the eradication of contact ads by law would help to eliminate situations of sexual exploitation, as well as to have a clear pedagogical impact on society, delegitimizing violent practices. But it is also true that, as pointed out by the editors of the press, it seems incongruous to outlaw advertising of prostitution without considering the legality of prostitution itself. That debate, being transcendental and highly topical in democratic societies, should also be opened in our country.

REFERENCES

1. APRAMP (2005). La prostitución: claves básicas para reflexionar sobre un problema Madrid: Fundación Mujeres. Recuperado de http://www.mujeresenred.net/IMG/pdf/prostitucion-claves_basicas.pdf.

2. Asociación para la Autorregulación de la Comunicación Comercial (Autocontrol) (1996). Código de conducta publicitaria. Recuperado de http://www.autocontrol.es/pdfs/Cod_conducta_publicitaria.pdf.

3. Ballester R, et al (2014). Exposición involuntaria: impacto en usuarios y no usuarios de cibersexo. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1):517-526.

4. Bernstein E (2001). The meaning of the Purchase: Desire, Demand and the commerce of sex. Ethnography, 2(3):389-420.

5. Boletín Oficial de las Cortes Generales (2007). Informe de la Ponencia sobre la Prostitución. Recuperado de http://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L8/CORT/BOCG/A/CG_A367.PDF.

6. Boletín Oficial del Estado (1988). Ley 34/1988, de 11 de noviembre, General de la publicidad. Recuperado de https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1988/BOE-A-1988-26156-consolidado.pdf.

7. Boletín Oficial del Estado (2004). Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género. Recuperado de https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2004/BOE-A-2004-21760-consolidado.pdf.

8. Boletín Oficial del Estado (2007). Ley Orgánica 3/2007, de 22 de marzo, para la igualdad efectiva entre hombres y mujeres. Recuperado de https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2007/03/23/pdfs/A12611-12645.pdf.

9. Carracedo R (2011). Prostitución y trata. Themis, Revista jurídica de igualdad de género, 7, 22-28.

10. Castellanos E, Ranea B (2013). Investigación sobre prostitución y trata de mujeres. Recuperado de https://goo.gl/WUG9HV.

11. Cobo R (2016). Un ensayo sociológico sobre la prostitución. Política y Sociedad, 53(3):897-914.

12. Cobo R (2015). El cuerpo de las mujeres y la sobrecarga de sexualidad. Investigaciones Feministas, 6, 7-19.

13. Connell RW (2003). Masculinities, change and conflict in global society: thinking about the future of men’s studies. Journal of Men’s Studies, 11(3):249-266.

14. Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucía (2016). Los estereotipos sexistas a través de los anuncios publicitarios en el espacio mediterráneo. Recuperado de http://www.consejoaudiovisualdeandalucia.es/sites/default/files/informe/pdf/1607/informe_estereotipos_de_genero_en_publicidad.pdf.

15. Consejo de Estado español (2011). Informe sobre las posibilidades de actuación contra anuncios de contenido sexual y prostitución publicados a diario en diversos medios de comunicación de prensa escrita. Recuperado de http://www.consejo-estado.es/pdf/Anuncios%20de%20contenido%20sexual%20y%20prostitucion%20en%20prensa.pdf.

16. Consejo de Europa (2011). Convenio de Estambul sobre prevención y lucha contra la violencia contra las mujeres y la violencia doméstica. Recuperado de http://www.msssi.gob.es/ssi/igualdadOportunidades/internacional/consejoeu/CAHVIO.pdf.

17. Código deontológico y de autorregulación para la publicidad y la comunicación no sexistas en Euskadi (2016). Recuperado de http://www.emakunde.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/temas_medios_intro/es_def/adjuntos/begira.codigo.deontologico.pdf.

18. Comisión Europea (2016). Informe de la sobre los progresos realizados en la lucha contra la trata de seres humanos. Recuperado de http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016DC0267.

19. De-Miguel A (2015). Neoliberalismo sexual. El mito de la libre elección. Madrid: Cátedra.

20. De-Miguel A (2012). La prostitución de mujeres, una escuela de desigualdad humana. Revista Europea de Derechos Fundamentales, 19, 49-74.

21. Diario El Mundo (2010). Aído, contra los anuncios de una actividad legal. 14 de mayo, p. 3.

22. Diario El Periódico (2016). Los editores rechazan que se creen restricciones publicitarias Recuperado de http://www.elperiodico.com/es/noticias/sociedad/los-editores-rechazan-que-creen-restricciones-publicitarias-391068.

23. Engman E (2007). Prostitución y tráfico de mujeres. Las actitudes en Suecia y las experiencias para combatirlo. Hermes Revista de Pensamiento e Historia, 23, 4-8.

24. Escolar Arsenio (2015). Metiendo el dedo en el ojo. En ¡Que paren las máquinas! Recuperado de http://blogs.20minutos.es/arsenioescolar/2015/03/12/metiendo-el-dedo-en-el-ojo-al-periodismo/

25. Estudio General de Medios (EGM) (2016). Resumen general de resultados de Febrero a Noviembre de 2016. Recuperado de http://www.aimc.es/-Datos-EGM-Resumen-General-.html.

26. Gutiérrez-García Andrea (2013). La actualidad del abordaje de la prostitución femenina en la prensa diaria Española. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 19 (edición especial), 823-831.

27. Mackinnon C (2010). La pornografía es una rama de la prostitución. Entrevista Clarín. Recuperado de http://entremujeres.clarin.com/genero/pornografia-rama-prostitucion_0_1334268437.html.

28. Martín R (2011). Prostitución, anuncios publicitarios y principios constitucionales. Teoría y Realidad Constitucional, 28, 597-608.

29. Meneses C, Uroz J, Rúa A (2016). Apoyando a las víctimas de trata. Recuperado de http://www.violenciagenero.msssi.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/estudios/investigaciones/2015/pdf/Apoyando_Victimas_Trata.pdf.

30. Observatorio de la Imagen de las Mujeres (2014). Informe 2014. Recuperado de http://www.inmujer.gob.es/observatorios/observImg/informes/docs/Informe2014.pdf.

31. OHCHR (2013). Gender Stereotyping as a Human Rights Violation. Recuperado de http://www.ohchr.org/SP/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CEDAW.aspx.

32. Parlamento Europeo (2014). Informe sobre explotación sexual y prostitución y su impacto en la igualdad de género. Comisión de Derechos de la Mujer e Igualdad de Género. Recuperado de https://goo.gl/b64CAM.

33. Pateman C (1995). El contrato sexual. Barcelona: Anthropos.

34. Red Par (Periodistas de Argentina en Red-Por una comunicación no sexista) (2012). Decálogo para el abordaje periodístico de la trata y la explotación sexual. En El delito de trata de personas. Su abordaje periodístico. Recuperado de http://www.fundacionmariadelosangeles.org/micrositios/delito-de-trata-de-personas/cuadernillo_trata_FINAL_web.pdf.

35. Szil P (2007). Pornografía, prostitución y los hombres. Intervención ante la Comisión Mixta de los Derechos de la Mujer y de la Igualdad de Oportunidades. Boletín Oficial de las Cortes Generales españolas, 379, 84-89.

36. Torrado-Martín-Palomino E, González-Ramos A (2014). Laissez faire, laissez passer, La mercantilización sexual de los cuerpos de las mujeres y las niñas desde una perspectiva de género. Dilemata. Revista Internacional de Éticas Aplicadas, 16(67):85-100. Recuperado de http://www.dilemata.net/revista/index.php/dilemata/article/view/329/345.

37. Torrado-Martín-Palomino E, Pedernera L (2015). La prostitución desde la perspectiva de la demanda: amarres enunciativos para su conceptualización. Revista Oñati Socio-legal Series. Recuperado de http://ssrn.com/abstract=2707090.

38. Torres MC (2012). Prensa escrita y anuncios de contacto ¿libertad sin igualdad? Análisis crítico desde un enfoque de género y constitución. Libros de Actas del I Congreso Internacional de Comunicación y Género. Sevilla, 5-7 de marzo. Recuperado de https://idus.us.es/xmlui/handle/11441/34040.

39. Voolma H, Trujillo M (2012). Reading between the lines. Examining the links between advertisements for sexual services and trafficking for sexual exploitation. Recuperado de https://maryhoneyballmep.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/reading-between-the-lines_final_mh.pdf.

40. Weber I, Jaimes A (2011). Who Uses Web Search for What? And How? En Proceedings of the Forth International Conference on Web Search and Web Data Mining (pp. 15-24). Hong Kong, China.http://courses.cs.byu.edu/~cs653ta/Literature/Web-Search/Who-What-How.pdf.