doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.140.115-129

RESEARCH

THE DISCOURSE ON ENTREPRENEURSHIP OF WOMEN FROM A GENDER PERSPECTIVE

EL DISCURSO SOBRE EL EMPRENDIMIENTO DE LA MUJER DESDE UNA PERSPECTIVA DE GÉNERO

O DISCURSO SOBRE O EMPREENDIMENTO DA MULHER DESDE UMA PERSPECTIVA DE GÊNERO

Pilar Ortiz García1 University Professor. Sociology Department. Faculty of Economics and Business. University of Murcia. Education: Bachelor of Sociology (Complutense University of Madrid) PhD in Economics (University of Murcia). Research: Participation in a total of 36 Research Projects. Out of them, 7 belong to the National R & D Plan of the Ministry of Science and Innovation and in 2 of them she was Main Researcher. Author of 34 articles, 25 of them in indexed journals with a relative quality index, 9 books and 43 book chapters as an author or a coauthor. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7679-0772

1Department of Sociology of the Faculty of Economics and Business. University of Murcia. Spain

ABSTRACT

This paper deepens the factors involved in the determination to undertake, in particular, in the entrepreneurship initiative of women. It also aims to detect the elements prone to limiting such initiative. It ultimately explores the differences of this fact with respect to their male counterparts. The gender perspective makes it possible to reveal through the discourse the roles assigned to the female entrepreneur as a woman. To fulfill this purpose, a qualitative methodology based on the discourse analysis of 10 in-depth interviews with entrepreneurs of both sexes has been used. The analysis of these interviews has allowed us to establish a set of conclusions on the perception of entrepreneurship from the perspective of the entrepreneurial woman in Spain. The gender perspective allows us to observe the differences in the discourse of men and women as a reflection of a different position with respect to economic activity. As a result, the results of the discourse analysis emphasize the importance of social support and integral training for the creation of a culture that promotes and makes visible the role of entrepreneurial women in an area such as the economic one, still masculinized.

KEY WORDS: Discourse, Entrepreneurship, Woman, Skills, Training, Culture, Roles

RESUMEN

Este trabajo profundiza en los factores que intervienen en la determinación a emprender, en concreto, en la iniciativa emprendedora de la mujer. También pretende detectar los elementos susceptibles de limitar dicha iniciativa. Por último, se indaga en las diferencias de este hecho con respecto a sus homólogos varones. La perspectiva de género posibilita desvelar a través del discurso los roles asignados a la emprendedora en su condición de mujer. Para cumplir este propósito se ha utilizado una metodología cualitativa basada en el análisis de discurso de 10 entrevistas en profundidad a emprendedores de ambos sexos. El análisis de estas entrevistas ha permitido establecer un conjunto de conclusiones sobre la percepción del emprendimiento desde la perspectiva de la mujer empresaria en España. La perspectiva de género permite observar las diferencias en el discurso de hombres y mujeres como reflejo de una posición diferente respecto a la actividad económica. En consecuencia, con esta posición, los resultados del análisis de discurso destacan la importancia del apoyo social y la formación integral para la creación de una cultura que promueva y visibilice el papel de la mujer emprendedora en un ámbito como el económico, todavía masculinizado.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Discurso, Emprendimiento, Mujer, Competencias, Formación, Cultura, Roles

RESUMO

Este trabalho aprofunda nos fatores que intervêm na determinação a empreender, em concreto, na iniciativa empreendedora da mulher. Também pretende detectar os elementos suscetíveis de limitar essa iniciativa. Por último, se indaga nas diferenças deste feito com respeito a seus respectivos varões. A perspectiva de gênero possibilita desvelar através do discurso, este papel destinado a empreendedora em sua condição de mulher. Para cumprir este propósito se utilizou uma metodologia qualitativa baseada na analises de discurso de 10 entrevistas em profundidade aos empreendedores de ambos os sexos. As analises destas entrevistas permitiram estabelecer um conjunto de conclusões sobre a percepção do empreendimento desde a perspectiva da mulher empresária na Espanha. A perspectiva de gênero permite observar as diferenças e o discurso de homens e mulheres como reflexo de uma posição com respeito à atividade econômica. Em conseqüência, com essa posição, os resultados das analises do discurso destacam a importância do apoio social e a formação integral para a criação de uma cultura que promova e torne visível o papel da mulher empreendedora num âmbito como o econômico, todavia masculinizado.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Discurso, Empreendimento, Mulher, Competências, Formação, Cultura, Papel

Received: 17/02/2017

Accepted: 05/05/2017

Published: 15/09/2017

Correspondence: Pilar Ortiz García. portizg@um.es

This paper is part of the project “Women and Entrepreneurship from a Competence Perspective” (CSO2013 - 43667 - R), developed by the University of Murcia and Bradford (United Kingdom) and funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Madrid, 2014-2016).

1. INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurship has acquired a special main role in an economic and political scenario marked by the economic crisis. In this context, the activation of the entrepreneurial initiative is proposed as a solution to the high unemployment rate in economies such as Spain. However, as in the labor market, in the entrepreneurial activity there is a gender bias that puts women at lower rates in relation to this activity (Guemes et al., 2011).

The economic crisis the country has gone through since 2008 has had devastating consequences on the employment of men and women. It is noteworthy that in this latest crisis the unemployment rates of both sexes have tended to equalize due to the massive loss of employment in sectors such as construction or the automotive industry, strongly masculinized. However, since the outbreak of the crisis, the unemployment rate of women has remained above that of men in Spain. But, in addition, crises often have a particularly harmful effect on women’s employment. As research on the subject has shown, after a crisis, women’s employment takes longer to recover than men’s (Gálvez and Torres, 2010; Gálvez, 2011); in addition, it tends to undergo significant intensification and precariousness ( Ortiz, 2014) and, consequently, a global decline in equality in the labor market.

The unemployment rate higher than 20% lasting more than five years in Spain has shown, on the one hand, the severity of the crisis and, on the other hand, the limited capacity of the economy and the public authorities to reverse this situation. Entrepreneurship appears as a possible way out, although the frontier between this activity and self-employment is increasingly difficult to draw.

In Spain, gender differences are reflected in the lower propensity for entrepreneurship in the case of women. Data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2013; 2014) for Spain in 2014 show that six out of ten early-stage entrepreneurs were men. This percentage is similar to that given among entrepreneurs who have consolidated their company. This translates into a rate of entrepreneurial activity (TEA) of 4.6% in women and 6.4% in men. This difference has remained over time, although since 2013 there has been a trend towards the approximation of both rates. The TEA rate is showing the greater propensity of men to undertake, therefore, it is of interest to know what the limitations in the entrepreneurial intention of women are. Out of the different approaches to address the study of this issue, gender is especially relevant, since the explicit gap with respect to the TEA rate is a reflection of the segmented construction of the labor market based on gender relations.

The gender perspective allows us to observe the differences in the discourse of men and women as a reflection of a different position with respect to the economic activity. Consequently with this theoretical perspective, the results of the discourse analysis emphasize the importance of social support and integral training for the creation of a culture that promotes and makes visible the role of the entrepreneurial woman in an area like the economic one, still masculinized.

1.1. Entrepreneurship in a gender key

Entrepreneurship is a complex and multicausal phenomenon. Therefore, it has been approached from different perspectives. The research on the subject has shown that, although it is interesting to define the profile of the entrepreneur, it is not less important to know the factors of the environment that can lead to the entrepreneurial initiative that this entails.

A brief synthesis of the research on the factors that condition - either positively or negatively - the entrepreneurial action points to three broad lines of analysis.

From an economic and institutional perspective, entrepreneurship has been analyzed as a rational action conditioned by the economic situation, the functioning of markets and the institutional environment (North, 1990; Alvarez et al., 2012: 44).

Another perspective has been the psychological one. From McClelland’s (1961) precursor analyzes, the entrepreneur’s psychological profile has been one of the main arteries of the study of entrepreneurship. Along with the traits of the personality of the entrepreneur identified by the author (originality, creativity, innovation), other papers such as those of Boydston et al. (2000) have focused on the attitudinal and aptitudinal components of this figure, however, no conclusive definitions have been arrived at about that profile.

Since the eighties, the sociological perspective has been linked to these perspectives. This line of work reflects the determination of contextual factors in the development of the entrepreneurial activity. Thus, from labor factors such as the aspiration to improve the working conditions, to social reasons such as recognition, they have been variables managed in the typification of entrepreneurship (Shapero and Sokol 1982, Evans and Lighton, 1989). From integrative perspectives, to the profile of the entrepreneur, elements of analysis are added, such as the environment in which it operates, institutional or social support (Ortiz and Millán, 2011). The gender approach corresponds to this category of studies in which socio-demographic characteristics such as sex or age are considered determining variables of entrepreneurship, taking into account that they condition the way in which the individual is introduced into the economic activity and the relationships that are established on the basis of these conditions.

Sex appears as a frequent variable in the study of entrepreneurship, however, the gender perspective has not been extensively explored in research on the subject. In recent years, this line of analysis has started to be relevant given the moderate, albeit constant, increase in female entrepreneurial activity, an activity that, however, does not grow at the same rate as the incorporation of women into the labor market.

Tangible and objective elements, such as the economic or training resources needed to undertake, as well as other intangible ones, such as the social consideration of this activity or the roles associated with the entrepreneur, are factors to be taken into account when analyzing this issue. Gender belongs to the latter type of factors. There are not many studies that focus on identifying substantial differences in entrepreneurship on the basis of gender, so delving into this field is of special interest.

The entrepreneurial activity is conditioned by various aspects of a “formal” (ie, objective and infrastructural) and “informal” (linked to the personality of the female entrepreneur or socio-cultural factors, including gender) nature.

Some studies have focused on identifying the influence of institutional aspects on the entrepreneurship of women. Access to funding, training or the existence or non-existence of collaborative social networks are elements liable to have an impact on entrepreneurship, generating differences according to the sex of the entrepreneur.

Regarding the former of the factors we mentioned, funding, several pieces of research have shown that there are differences in the negotiation process that can cause variations in the level of indebtedness or in the access of the female entrepreneurs to funding (Alsos et al., Carter et al., 2007; Gatewood et al., 2009).

As for factors such as training, there is no unanimity on the influence on the entrepreneurship of women. Authors such as Fairlie and Robb (2009) identify a positive relationship between the educational level and the results obtained with the entrepreneurial activity; however, other authors observe that the level of studies does not affect the results of such activity, neither is gender decisive (Grilo and Irigoyen, 2006). To this conclusion also comes the research of Álvarez et al. (2012), to whom formal factors such as funding, training or non-economic supporting policies have little relevance to women’s decision-making, given the significant incidence of informal factors.

On the other hand, research emphasizing the influence of informal factors analyzes socio-cultural (Alvarez and Urbano, 2011), or competence (Ortiz and Olaz, 2016) factors that are relevant in the differential character of entrepreneurship according to gender. The influence of these elements translates into the greater or lesser impetus of women’s entrepreneurial activity. Included in these factors are the perception of entrepreneurship skills, social networks and the family role (Álvarez et al., 2012).

From the gender perspective, this piece of research focuses on the informal aspects related to the perception of skills and competences, family relationships and social networks as moderators of the entrepreneurial intention of women.

Taking into account the theoretical background, the starting hypothesis of this paper is that the divergence in entrepreneurship rates between men and women has to do with both structural and cultural factors.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this paper is to know the factors involved in the entrepreneurial initiative of women.

Secondly, we seek to identify the elements likely to limit that initiative.

Finally, we research the differences of this fact with respect to their male counterparts.

3. METHODOLOGY

This piece of research used a qualitative methodology based on the discourse analysis from in-depth interviews to entrepreneurs of both sexes. The analysis of these interviews made it possible to establish a set of conclusions on the perception of entrepreneurship from the perspective of female entrepreneurs in Spain.

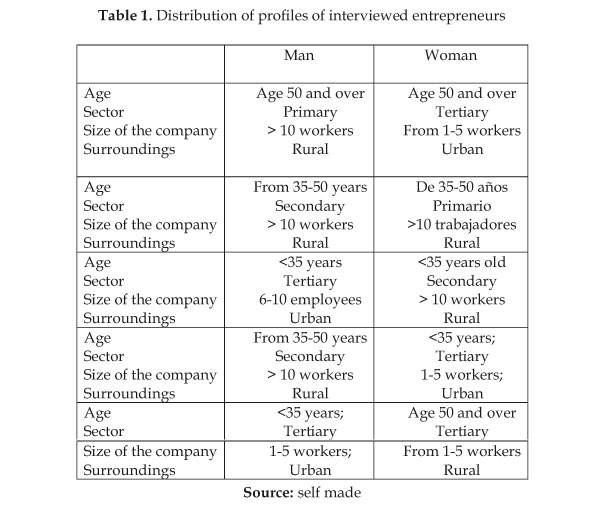

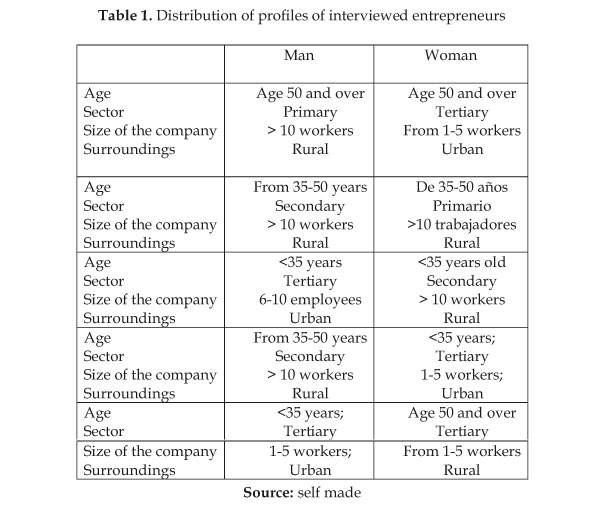

A total of 10 in-depth interviews were conducted with entrepreneurs (five men and five women) appointed according to criteria suitable to the research purposes (sex, age, activity sector, company size and environment).

The distribution of profiles is shown in Table 1:

The interviews, conducted from February to March 2015, were recorded for later transcription and analysis through the ATLAS.Ti software for qualitative treatment of data. The use of this software has allowed us to perform an analysis at two levels. In a first level, the tools: “word examiner”; “appointment consultation”; “co-occurrence table” and “code table of primary documents” have led to a descriptive analysis of texts. In a second level, a relational analysis has been carried out based on the construction of “semantic code networks”, which has led to the establishment of useful semantic links for a comprehensive analysis of the factors that contribute to the entrepreneurship of women.

3.1. The analyzed issues

Although research has been conducted on an extensive questionnaire, this paper focuses on two issues. The choice of both aspects is due to the intention to respond to the hypothesis raised about the incidence of structural and cultural factors in the performance of the entrepreneurial activity of women.

The first question was formulated in these terms: What elements (scenarios, variables, aspects) would help to empower women’s entrepreneurship? This issue, in turn, includes the following aspects:

−“Conciliation policies or policies related to it”.

−“Actions aimed at creating an entrepreneurial culture, specific training and giving visibility to female entrepreneurship”.

−“Realization of changes in working hours”, aimed at achieving better rationalization of working and personal time.

−“Associationism”.

−“Implication of the Administration”.

−“Crisis scenario”.

The second question was formulated as follows: Suppose that you start from “zero” again in your entrepreneurial action, what training support would you like to receive / consider important to consider undertaking? and familiar? and the environment? The following categories correspond to this question:

−“Support at training level that you would have liked to receive to undertake”.

−“Family support that you would have liked to receive to undertake”.

−“State support that you would have liked to receive to undertake”

−“Support of groups or associations that would have liked to receive to undertake”.

4. RESULTS

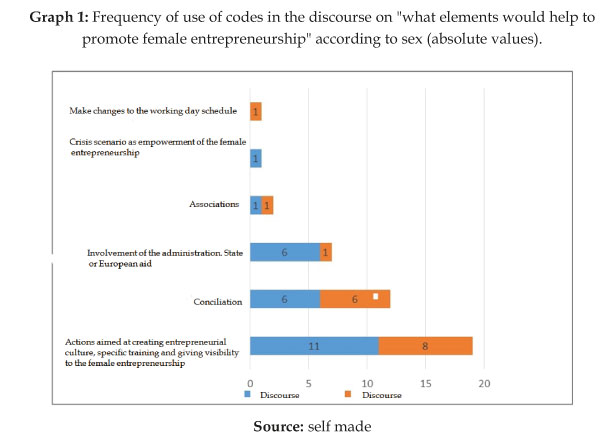

From a descriptive perspective, the results allow us to dimension the reiteration in the discourse of proposals on the actions that help the entrepreneurship of women according to the established codes (Graph 1). They highlight the importance given by entrepreneurs (men and women) to “Actions aimed at creating an entrepreneurial culture, training and visibility for entrepreneurship of women” (it appears in quotations of the discourse of men on 11 occasions and 8 in that of women ).

Secondly, there are the issues related to “Conciliation” (in the same order of importance for both sexes).

With a notable difference, mention is made of the “Aid provided by the Administration”, although in this case, although it appears repeatedly in the discourse of men (in 6 occasions), it is not the case in the discourse of women, where this allusion is absent.

On the other hand, “Associationism” as an aid to entrepreneurship is mentioned on just a few occasions (1 each of the blocks of discourse according to sex), which indicates the lesser importance granted to it, as in the case of “Crisis as a promoter of entrepreneurship” or “Making changes in the working hours” to help female entrepreneurship.

4.1. Differences regarding the elements enhancing entrepreneurship of women in the discourse of entrepreneurs

In the discourse of entrepreneurs, one of the issues that calls for a greater degree of agreement is: “the support of actions aimed at creating an entrepreneurial culture that encourages and makes female entrepreneurship visible.” This topic is key to respondents regardless of sex.

Without undermining the relevance that has to establish the points of coincidence in the discourse, the analysis that shows more interest is the one that shows the differences between both sexes. In this regard, the content analysis of the discourses shows that women emphasize the “recognition” of the work of the entrepreneur as one of the pillars for the extension of this economic activity, an issue that does not appear in the discourse of men:

–Now they are giving recognition to women’s entrepreneurial projects.... recently, an associated girl from OMEP has set up a very small company, with two or three people, it is a diets company.... and they have given her recognition, we awarded her with the prizes of OMEP, then she has been awarded by the City Council, then they are giving her recognition in Antena 3 because it is a matter of nutrition and child nourishment.... All this makes women to be in that world every time. We get more empowered.... That’s like gunpowder, right? It runs as fast as gunpowder but those people who are finishing their studies and see that women are gaining access, well, it is an incentive to wanting to undertake (E2-Woman).

–The second difference appears when referring to the education of this entrepreneurial spirit. Women appeal to education with an integral sense, of a “humanist” nature, beyond the actions of formative, while, in the discourse of the men, there is insistence on the actions of training and communication with a specific sense, linked to the professional role of the entrepreneur. Not only to women, to women and men it would be the same, training. But not technical training, but human. That is, basically it would be to lose one’s fear, which is a matter of personal work, and also of social education that is not learned at school, when it should be learned at school. Basically it is training (E3-Woman).

–If you have a back-to-business training you already have training, now it is important for the business you are going to undertake that you have the knowledge in that business or in the activity that is going to be undertaken. For example, we are in meat and tomorrow we say that we are going to start another business and we will make car wheels, then we will have to have training or vision within that business to undertake it. Because what training is at the level of personnel, banks, what the structure of the company is, you already have it (E7-Man).

Another difference in the discourses of the interviewees revolves around the fact that female entrepreneurs also emphasize training aspects linked to the development of resources such as leadership. This issue is possibly pointing to what is socially “labeled” as lack or weakness associated with the role of women’s subordination in the productive sphere.

–Training and leadership [...] I believe that, from school, a lot of things can be done, from the universities too [...] More debates in class, to increase criticism within communication and leadership (E1-Woman).

The allusion to leadership as a training need is practically absent in the discourse of male entrepreneurs, in this case, the interest is in training aspects of practicality:

–[...] Because they teach you the pros and cons, taxation how it works and they have specific workshops that can do you good, not about leadership, but about managing your own company or setting up your website (E9-Man).

A fourth distinctive element in the discourse of women with respect to men emerges when referring to aspects related to conciliation policies. Female entrepreneurs continue to demand co-responsibility as an obligation; however, men demand this aspect as a “right” to “enjoy” the family as leisure time:

–When you are the head of a company you are very involved, when you are not you are dependent on a schedule imposed on you [...]it is that we men also have the right to be with our family (E9-Man).

–I believe that we have been talking to women about conciliation for 30 years now. I believe that we must now teach men to reconcile (E2-Woman).

–[...] And a greater obligation of men in the familiar aspect that would make easier to women to occupy positions of greater responsibility (E5-Woman).

The fifth difference in the discourse according to the sex of the interviewed entrepreneur is related to the opinion on the role of state aid for entrepreneurship. In general, as regards men, it appears as a measure of acceptable positive discrimination, however, to women, it is not only virtually absent in the discourse as a measure of support but, when referring to economic aid in general (not necessarily state aid), Its effectiveness is not perceived:

–In short, I see these aids.... those that are not to train when undertaking or to train in how to create your company, other than that, I see all the others ineffective (E1-Woman).

–Maybe if the issue of women already requires that and it is valued, well I would agree to grant it, but to projects of reliability, not to any project (E6-Man).

A sixth difference in the discursive output by reason of the sex of the interviewees is evidenced with respect to the elements potentially driving entrepreneurship, as it is the case of associationism. Although not too much present in discourses, when it appears, it is given great importance by women, not so in the case of men:

–Part of women’s associations, such as OMEP. helps you a lot because it helps you to realize that all these fears, doubts, challenges, concerns are shared by everyone, and by all women (E4-Women ).

–I do not hear that an association is going to be set up and women are going to go out.... (E7-Man).

The seventh and final distinctive aspect of both discourses appears in the themes associated with the rationalization of working days as a measure of support for entrepreneurship. Rationalization of schedules is not perceived by men as a strategic element, in view of its null presence in their discourse. On the other hand, to women, without being strategic, the change in the schedule would be of help:

–The schedule in Spain, the change in the schedule. The schedule does not help us anything. Those so long working days (E2-Woman).

Summing up, these are differential aspects that show a different sensitivity to the factors that boost entrepreneurship as a result of different positions in relation to economic activity.

4.2. Differences regarding the support needed to drive female entrepreneurship in the discourse of entrepreneurs

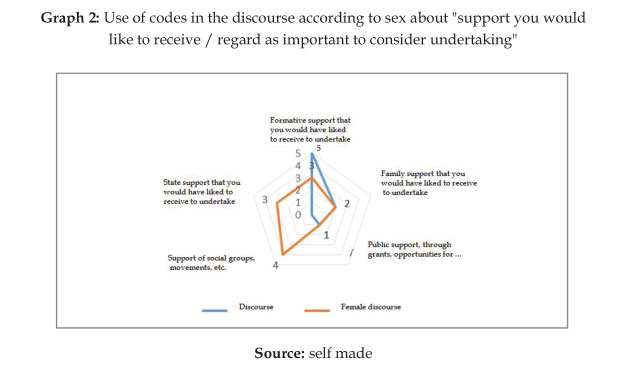

Regarding the second issue under research, that is the support for entrepreneurial initiative and its perception by interviewees, the results of the query (Graph 2) show -once more- the importance of training for both sexes, in particular, the demand for more training to undertake the activity with expectations of success.

Some of the highlights in this analysis are the few allusions to the importance of family support in the discourse of women -in the same way as men-, but when referring to it, it becomes relevant to both women and men:

–Having a favorable social environment, I mean, if you are married or have a partner that supports you, if you live with your parents, who support you.... because, otherwise, it is going to be very complicated (E1-Woman).

–Family support, yes, family support has always been to support me in what I have already decided to be the best as to whether I decided to study or to work and, in that sense, I have never had any trouble (E8-Man).

As for social (groups or movement) or state support, both elements are highly relevant in the discourse of women, while they do not appear in that of men.

Despite being a strategic element, among the female entrepreneurs, there is a critical difference regarding public subsidies. Rather, what women demand from the state is ease in the formalities and procedures for the creation of companies:

–The only thing that the Administration has to do. Why do I say the only thing? Because I don’t agree on subsidies, non-refundable subsidies to help undertake [...] I don’t agree that public administrations put so many obstacles when undertaking, with permits, licenses, paperwork... and taxation, of course (E1-Woman).

There is also a gender difference in relation to the demand for social support, much more present in the discourse of female entrepreneurs than in that of their male counterparts:

–I would have missed someone who could have grasped my basic idea that would have helped some people that had more or less similar ideas to get in touch and in common (E3-Woman).

5. DISCUSSION

The results of the analysis of the discourse about entrepreneurship have allowed us to identify some gender differences in the factors contributing to the entrepreneurship of women. In this sense, although training is important for both sexes - as it would be in tune with the conclusions of studies such as that by Fairlie and Robb (2009) -, the meaning and the measures demanded are different: whereas, in men, it appears linked to business functions, in women it takes on a more global character, while insisting on the training of managerial skills, such as leadership. Conciliation also has different nuances on the basis of gender. Women show in their discourse the need for co-responsibility in domestic and family tasks, whereas, in the discourse of men the “right” to conciliate appears. This aspect highlights the gap that still exists with regard to care and dedication to care between men and women, as the recent study by Diaz (2016) shows. The third element, in order of importance, in which there is difference in the discursive argumentation of male entrepreneurs vis-a-vis women is state aid. Thus, to men it is a positive measure, whereas to women it is, in general, ineffective. This same difference can be seen when the entrepreneurs - men and women - express themselves on the support they would have needed to undertake. Basically, women emphasize social support, while men insist on formal aspects such as training.

The demand for actions by the State is also different according to the sex of the entrepreneur, showing the skepticism of women about their effectiveness, compared to the positive perception of men.

The results also highlight the importance of social support and comprehensive training in the creation of a culture that promotes and makes visible the role of entrepreneurial women. A fact that confirms the starting hypothesis about the key role played by cultural and social elements, as identified by Álvarez et al. (2012).

These conclusions point to four major dimensions in which action must be taken for the empowerment of female entrepreneurship in a scenario capitalized by men.

On the one hand, in the social dimension, women demand the promotion of an entrepreneurial culture that channels the formation of this spirit and helps to make visible and recognize their role in entrepreneurship.

From the personal dimension, the discourse of female entrepreneurs shows the importance given to training as a factor to support entrepreneurship, which recommends undertaking specific training programs for entrepreneurial women.

As for the family dimension, although it is not a recurring element in the discourse of women, it continues to have an important gender bias, as evidenced by the argument about co-responsibility - of the female entrepreneurs - against that of conciliation as a “right” to enjoy the family - of the male entrepreneurs. Lastly, the economic-financial dimension appears, although it is not particularly present in the discourse of female entrepreneurs as a problem, it acquires the importance of a facilitating factor.

REFERENCES

1. Alsos GH, Isaksen E, Ljunggren E (2006). New Venture Financing and Subsequent Business Growth in Men-and Women-Led Businesses, Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 30(5):667-686.

2. Álvarez C, Urbano D (2011). Una década de investigación sobre el GEM: logros y retos, Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, nº 46, 6-37.

3. Álvarez C, Noguera M, Urbano D (2012). Condicionantes del entorno y emprendimiento femenino. Un estudio cuantitativo en España, Economía Industrial, 383(1):43-52.

4. Boydston M, Hopper L, Wright A (2000). Locus of control and entrepreneurs in a small town. Recuperado de http://www.sbaer.uca.edu/docs/2000 asbe/00asbe188.htm.

5. Carter S, Shaw E, Lam W, Wilson F. (2007). Gender, Entrepreneurship, and Bank Lending: The Criteria and Processes Used by Bank Loan Officers in Assessing Applications, Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31(3):427-444.

6. Díaz C (2016). Brecha Salarial y Brecha de Cuidados. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch.

7. Evans D, Lighton L (1989). Some empirical aspects of entreprenership, American Economic Review, 79(3):307-327.

8. Fairlie RW, Robb AM (2009). Gender differences in business performance: evidence from the Characteristics of Business Owners survey, Small Business Economics, 33(4):375-395.

9. Gálvez L (2011). La desigualdad de género en las crisis económicas, Investigaciones Feministas, 2, 113-132.

10. Gálvez L, Torres J (2010). Desiguales mujeres y hombres ante la crisis financiera. Barcelona: Icar.

11. Gatewood EJ, Brush C, Carter N, Greene P, Hart M (2009). Diana: a symbol of women entrepreneurs’ hunt for knowledge, money, and the rewards of entrepreneurship, Small Business Economics, 32(2):129-145.

12. Guemes JJ, Coduras A, Rachida CC, Pampillon R (2011). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Informe Ejecutivo 2010. España: I E Business School.

13. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2013). Informe Monográfico sobre Género. Extremadura 2003-2011. Fundación Xavier de Salas: La Coria.

14. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2014). Informe GEM España 2014. Santander: Editorial de la Universidad de Cantabria.

15. Grilo I, Irigoyen JM (2006). Entrepreneurship in the EU: To Wish and not to be, Small Business Economics, 26(4):305-318.

16. Mcclelland DC (1961). The achieving society. New York: The Free Press.

17. North D (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

18. Ortiz P, Millán A (2011). Emprendedores y empresas. La construcción social del emprendedor, Lan Harremanak, 24, 219-236.

19. Ortiz P (2014). El trabajo a tiempo parcial ¿una alternativa para la mujer en tiempos de crisis?, Sociología del Trabajo, 82, 73-92.

20. Ortiz P, Olaz A (2016). Mujer y emprendimiento desde una perspectiva competencial. Cizur Menor (Navarra): Thomson Civitas-Aranzadi.

21. Shapero A, Sokol L (1982). The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship, en Kent C, Sexton D, Vesper KH (Eds.). The Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship (pp. 72-90). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.