doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.140.17-43

RESEARCH

FANS AND IDENTITY. SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS OF THE ETHICS OF ENDURANCE

HINCHAS E IDENTIDAD. ALCANCES Y LIMITACIONES DE LA ÉTICA DEL AGUANTE

TORCIDAS E IDENTIDADE. ALCANCES E LIMITAÇÕES DA ÉTICA DO AGÜENTAR

Germán Hasicic1 Licenciado en Comunicación Social (Or. Periodismo) y Técnico Superior Universitario en Periodismo Deportivo por la Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social (UNLP). En docencia, Jefe de Trabajos Prácticos en la Cátedra Prácticas Corporales y Subjetividad; Auxiliar diplomado en la Cátedra Sociología del Deporte (FPyCS- UNLP). Doctorando en Comunicación. Becario de Posgrado de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Área de investigación: Estudios Sociales del Deporte. Antropología del cuerpo y subjetividades. En gestión, Secretario Técnico-Administrativo de la carrera de posgrado Doctorado en Comunicación (FPyCS- UNLP) de 2014 a la fecha. Editor de “Colección Libros de Cátedra” entre 2014 y 2016 en la Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata (Edulp). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9302-9544

1National University of La Plata, Argentina

ABSTRACT

From a set of interviews, dialogues, conversations and informal talks were transformed into the protagonists of a research that approaches, among other subjects, the subjectivities from a socio-cultural perspective and not merely discursive. That is, the analysis of discursive practices is part of a broader and more complex analytic framework, articulating the questions by the underlying violence and discrimination. In order to get even deeper into the identity construction of River Plate fans, it is necessary to review the most significant discussions and developments around the studies related to the construction of soccer identities: how identities of these subjects are constituted, perceived and self-perceived, noticing the social behavior allowed and paying attention to the use of violence as a legitimate / illegitimate practice, developed in the previous chapter. In doing so, we have put in tension a moral category: the ethics of endurance.

KEYWORDS: Culture, identity, violence, endurance, fans

RESUMEN

A partir de un conjunto de entrevistas, diálogos, conversaciones y charlas informales se transformaron en los protagonistas de una investigación que aborda, entre otros ejes, las subjetividades desde una perspectiva socio-cultural y no meramente discursiva. Es decir, el análisis de las prácticas discursivas forma parte de un entramado analítico más amplio y complejo, articulándose a las preguntas por la violencia y la discriminación subyacentes. Para adentrarnos aún con mayor profundidad en la construcción identitaria de los hinchas de River, es preciso realizar una revisión de las discusiones y avances más significativos en torno a los estudios vinculados a la construcción de identidades futboleras: cómo se constituyen, perciben y autoperciben las identidades de estos sujetos, reparando en el comportamiento social permitido y atendiendo al uso de la violencia como práctica legítima/ilegítima, desarrollada en el capítulo anterior. Al hacerlo, hemos puesto en tensión una categoría moral: la ética del aguante.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Cultura, identidad, violencia, aguante, hinchas

RESUMO

A partir de um conjunto de entrevistas, diálogos e conversações informais se transformaram nos protagonistas de uma investigação que aborda, entre outros temas centrais, as subjetividades desde uma perspectiva sócio-cultural e não meramente discursiva. Ou seja, a analise das práticas discursivas forma parte de uma estrutura analítica mais ampla e complexa, articulando-se as perguntas pela violência e a discriminação subjacentes. Para adentrarmos com maior profundidade na construção da identificação dos torcedores do River, é preciso realizar uma revisão das discussões e avances mais significativas entorno aos estudos vinculados a construção de identidades futebolísticas: como se constituem, percebem e auto percebem as entidades desses sujeitos, reparando no comportamento social permitido e estando atento ao uso da violência como prática legitima/ilegítima comentada no capitulo anterior. Ao fazer pusemos em tensão uma categoria moral: a ética do agüentar.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Cultura, Identidade, Violência, Agüentar.

Received: 04/11/2016

Accepted: 19/12/2016

Published: 15/09/2017

Correspondence: Germán Hasicic. germanhasicic@gmail.com

1. INTRODUCTION

As mentioned above, the motivation of the research is articulated both in a subjective order, based on ethnographic work with subjects whose identities are socially, culturally and emotionally linked to the River Plate Athletic Club, as well as in an academic one, putting in tension categories and theories linked to the behavior or conducts of the public that attend the stadium to football matches, with the purpose of analyzing and problematizing the practices of discriminatory senses and folk reproductions in the construction of identities.

Initially, I had enough preliminary information to carry out the field work: familiarization with the field (the stadium) and with it an incipient selection of interviewees, the notion about the main theories related to social behaviors in soccer stadiums and different statistics (mainly those referring to the number of deaths due to violence and their respective circumstances). A priori, this scenario would be auspicious; however, it was imperative to avoid falling into a common trap, or rather, not to force an inquiry that would conform to the studies and theories made to date and, thus, culminate in a mere conceptual reiteration.

The latter is aligned to the methodological proposal, which was configured from a field that was vast and at the same time markable with boundaries. It should be noted here that there were significant issues that led to circumscribing and narrowing the spectrum of work to audiences who attended the Antonio Vespucio Liberti stadium in the matches that the First Division team played during the Final Tournament “Recovered Grandchildren” 2014 Raúl Alfonsín Cup (1): fundamentally, the decision of the national government to prohibit the attendance of public visitors to the stadiums, being implemented from September 2013. This figure is not less since, as we will see later, the dispute of symbolic capital with the other was seen to be invisible and impossible to be materialized in each of the meetings in the absence of these other vital interlocutors in the process of identity construction.

(1) It was the event that closed the eighty-fourth season of the professional era of the First Division of Argentine football. It was played during the first half of the year, between February 7 and May 19, organized by the Argentine Football Association. The champion was the River Plate Athletic Club, interrupting a period of six seasons without official titles. Source: Asociación de Fútbol Argentino (AFA). Online. Available at: <http://www.afa.org.ar/torneos.php>.

Field work was not limited to interviews and participating observation during matches, but also involved coffee talks with associates in the club’s confectionery (for example, the case of the “lifetimes” (2)), meetings with members of the “Javier Saviola” Berazategui and “Norberto Alonso” Baradero subsidiaries, as well as meetings in the vicinity of the stadium prior to the start of matches. We considered that a direct approach was essential to achieve a finished approach to them.

(2) Term with which I named a group of four life associates of Club Atlético River Plate. With them I had an extensive interview / conversation in the confectionery and the immediate vicinity of the club. It was valuable in pointing out some counterpoints to the “ethic of endurance” (Alabarces, 2014).

From a set of interviews, dialogues, conversations and informal talks were transformed into the protagonists of a research that approaches, among other axes, subjectivities from a socio-cultural perspective and not merely discursive. That is, the analysis of discursive practices is part of a broader and more complex analytic framework, articulating the questions by the underlying violence and discrimination.

In order to get even deeper into the identity construction of River fans, it is necessary to review the most significant discussions and developments around the studies related to the construction of soccer identities: how identities are constituted, perceived and self-perceived of these subjects, repairing the social behavior allowed and attending to the use of violence as a legitimate / illegitimate practice, developed in the previous chapter. In doing so, we have put in tension a moral category: the ethics of endurance.

Prior to his approach, it is necessary to approach other elementary issues that, inexorably, will lead to this problem. First, to answer a key question: what is a fan? A priori, this would not be inconvenient. However, the diverse and dissimilar definitions lead us to rethink whether there is a univocal sense or we are faced with a concept, in terms of Garcia Ferrando (1990), polysemic and mutable. The testimony of Sebreli, once again characterized by the absence of empirical foundations and plagued by prejudices and common sense, serves as a kick-start:

I think fanaticism is not innocent, it leads to murder. [...] I distinguish the fan from the barrabrava, who is interested. [...] The barrabrava is a protagonist today, because it brings drama, picturesqueness, coloration. Sometimes what happens in the stands is more entertaining than what happens on the court. I distinguish between the passive fan, who is dragged, and the barrabrava, which is the one that drags the other. [...] The predisposition to violence is not manufactured, it arises from questions of social psychology. These subjects are a variant of the authoritarian personality, essentially violent (3).

(3) See De Vedia, M. (1998, May). “The passion that awakens football has two faces.” In the Nation. Online: <www.lanacion.com.ar/97795-la-pasion-que-despierta-el-futbol-tiene-dos-caras>. Accessed January 20, 2016.

In turn, we can see the construction of an ideal fan on the part of the media and the advertising of certain products, which is embodied in cheerful people, who attend the stadium with their children in official hats and shirts. However, the idyllic cannot resist the multiplicity of realities. Alabarces ironizes about it:

This idyllic image of spectators, footballized but rational is threatened by others, the customary beasts, the barras bravas, the criminals that break into the arcadia of Argentine football. Fringe groups, alcoholics and drug addicts are, according to these descriptions, the exceptions. They are the germs, the disease. Only one remedy can be prescribed and it is their expulsion from the sacrosanct innocence of football. (Alabarces, 2012: 17)

In this last one we stop and point out a brief parenthesis: the stereotypes of fans molded by the media. What is a fan? Who is him? How is the River fan? Is there a single type of possible and legitimate fan? What role does the use of violence play in the identity process? The truth is that it has been modified itself and resignificated discursively over the decades.

2. DISSICUSION

2.1. What is a fan?

As Frydenberg (1997) points out, football has been consolidating itself since the beginning of the 20th century as a sports practice of the popular sectors, the so-called popularization process. From it began to form the first spectators - who were also protagonists - of the sporting event, although outside of the official circuits and the mass logic. There is no football without fans, but there is also no football without sports journalism. Both are born almost simultaneously. Football and modern sport are contemporary to the birth of the mass media.

To refer to the Argentine fans, or simply to the concept fan, it is imperative to leave aside clichés or superficialities. This leads us to review what has been said about it over the decades since the consecration of football as a mass phenomenon. That is, what representations have been built temporarily, where fans do things to be seen, for example, or reinterpret or transform their behaviors from the treatment that is made of them in the media.

In this sense, the work of Mariana Conde (4) offers an analysis of the press and its stereotypes, making visible what actors appear in the sports press and how they are characterized (5), where the dynamics of culture can be read in this variation (Hall, 1984).

(4) Bachelor of Science in Communication (UBA), Master in Sociology of Culture and Cultural Analysis (IDAES-UNSAM) and Doctorate in Social Sciences (UBA).

(5) See Conde, M. (2006). “The invention of the fan in the periodic press”, in Alabarces, P. (2006). Swollen Buenos Aires: Prometheus.

In the ‘40s there was an increase in the number of people, especially because the building conditions and infrastructure were guaranteed (the football thought massively). This expansion took place from social and economic conditions that allowed the enjoyment of free time in material and symbolic consumption. In fact, that decade and the next comprise the period of greater purchasing power of wages, which allowed the allocation of a significant portion to cultural consumption (Portnoy, 1972).

From the 1950s, an essentialist connection was made between the “fans”, the people and the nation, allowing the construction of political taxonomies that, as Garcia Canclini points out, referring to Bourdieu, “disguise themselves, or euphemize themselves, under the axiomatic aspect of each field. This is the ideological action of culture “(1990: 41). Towards the end of this decade, more or less homogeneous modes of definition are beginning to be detected. These insisted on naming the attendants to the sports grounds with the term “people”, abandoning their pejorative status of fringe groups. The headlines and articles in the newspaper Crónica show: “Football is the sport of the People and, because of the People, it is wonderful. And it is a compensation for the popular hardships, forgotten in the stadiums “(Crónica, April 14, 1967); “Football is for the People and from the People arise its protagonists” (Crónica, April 15, 1967).

This people was considered essentially noble, good. And it existed beyond the sphere of sport, articulated by the political discourse of Peronism, a period during which professional football would have become an imaginary place of national-popular epic.

In the 70’s, the fan is still the embodiment of all the good that can be in football: abnegation, fidelity. This was evidenced notably in the 1978 World Cup played in our country, where the enunciative strategy laid in the uncompromising exploitation of an inclusive “we”, by which the players, the fans, the military state and the Argentine people would be amalgamated.

In the 1980s the “barrabrava” significant emerged, which is absolutely negative in character and was popularized by sports journalists to account for those subjects who attended the courts and produced some violent act. From 1983, the violence appears unleashed, which leads to imagine a stage of “decomposition” of football, which turned out to be a kind of continuity of social decomposition. It was a fall in barbarism, that is to say on the other side of civilization (outlaws, beasts): “[...] football is dying: it lost its fan” (Crónica, August 4, 1983). So football was no longer seen as a popular holiday, because “things are being diverted.” For the journalistic chronicles, certain values that founded the essential practice of the fan had disappeared.

There is a gradual passage or transformation from the carnival to the violent, degraded. If we analyze the journalistic representations of violence in a thirty-year time frame, taking significant cases such as the death of Hernán Souto (1967), Puerta 12 (1968), the murder of Adrian Scaserra (1984), or those of Vallejos and Delgado (1994), we will find that the Buenos Aires newspapers Crónica, Clarín and La Nación have more coincidences and continuities than divergences and ruptures. In order to talk about the subjects involved in cases of violence, the central idea that appears in the coverages is that of “misfits”. At the same time, it is included within a group marked as illegal, whose practices lack, from that vision, any justification.

In the first place, criminal stigmatization prevails, using terms such as: patotero groups, patota, organized delinquents, criminal gangs; terms that account for a behavior presumably removed from the daily practices of a civilized society. Second, there are categories that refer to pre-social states: savages, barbarians, beasts, insane persons.

With respect to these coincidences in the stigmas and classifications, variations arise that depend from the historical context, on which the media do not offer explanations. They simply put lists of adjectives and collections of anecdotes. In no time do they develop causal foundations or link facts to broader contexts, except for the cliché of social violence, the economic crisis, the crisis of values or insecurity.

In the 1990s, on the other hand, the legitimized rhetoric of passion is the brand that distinguishes the true soccer fan, and is at the same time the only feature that can guarantee its survival, that from the previous decade, was in a state of decomposition. As Archetti (2003) points out, the language of morality is that of emotions; a sentimental speech. This rhetoric of the affects dominated by passion is linked to smaller groups than the “people”: the neighborhood. Thus, this passion manifests itself in relation to colors, that is, with a certain club, and not with a national football. There may be, for example, a “town” of River, a “town” of Boca, another of Gimnasia:

This is a moment of fragmentary groups, celebrating the local tribes, which are in turn sustained by a legitimate passion, because affective affiliations have become good. And the fan of Boca is cataloged as the climax of that contract of passion. Being of Boca, in spite of the racist stigmas or precisely for that reason, is a maximum mark of the investment in love, heart and endurance. Being from Boca is being popular, which is no longer bad, but transforms into an inverted distinction. (Alabarces, 2012, pp. 97-98)

In summary, in the history of the invention of the fan in the periodical press (and other texts) two moments stand out: in the first, relations between those fans and the nation to which that signifier refers and refers are discursively established; And in the second, the fans are basically neighborhoods.

For its part, television has also contributed to the construction of a stereotyped and, consequently, televised and televisable fan. The work carried out by Daniel Salerno (6) linked to the representations of the fans and the violence by the program “The Endurance” (7) shows the various aspects that integrate an alleged idiosyncrasy of the fan, where the most outstanding attributes were the songs and the display of flags. It not only described, but also prescribed: to appear on the screen he should be a model fan as required by the program.

(6) Bachelor of Science in Communication (UBA) and Doctor of Social Sciences (UBA).

(7) It was transmitted by TyC Sports from 1997 to 2008, under the leadership of Martín Souto and Pablo González. The program was based mainly on showing different fans of Argentine football and “what it was like to be a football fan”. In 2008, the channel joins a campaign against violence, which does not favor “El Aguante” that in a short time would have its last broadcast in which it was clarified that the program would be lifted from the air as it encouraged violence in The tribunes. In this sense, the cycle received constant criticism due to the entity granted to the barrabravas.

There was also the humor clause. In the program came out the racist, homophobic, xenophobic qualifiers, the threats and references to illegal drug consumption, which are used in turn by fans as positive reviews and negative appreciations of rivals. Here came the humor clause, which consisted in suspending the meaning of what was presented on the screen to assign new meanings: both the songs and the words of the interviewees were reduced to jokes, mere play games with which the fans nourish their symbolic rivalry and the racist qualifiers were part of that game “without consequences” That is, the confrontation between rival fans led to “play the threats.”

This centrality of the football identity is recovered by the media and the journalistic narrative. At the moment the fans magnify their protagonism in the story, in the televising of their carnivals or in the description of their actions. Advertisements constantly show situations where being a fan is not only legitimate, but the only possibility, “although the fans on stage are members of a middle class that in other times reserved the endurance to private life, to leisure time. The phenomenon is contemporary to the appearance in other countries of fictional or biographical narratives oriented towards the fans “(Alabarces, 2012, p. 91).

However, the media narratives are not enough but partial when defining what or who is a fan. For a more complete approach, we refer to the testimonies of the fans themselves, who until now, have not had a voice and because “the fans do not represent a wild horde, but a social order structured according to precise rules that its members must respect “(Archetti, 1985, pp. 88-89). We cannot understand what we are trying to describe without hearing the interpretation of the subjects themselves about their actions. This does not imply to take their testimonies as revealed truths, but to start from the verification that in these years was not tried or did not exist a genuine interest to understand the practices of the fans - among them, the violence - taking into account their own perspective. Without this perspective, “any interpretation is impossible, because it ignores a fundamental source: those who develop the actions that must be interpreted later” (Alabarces, 2012, p. 65).

Let us begin with the word of an historical called barrabrava of Boca, José Barrita (8), popularly known with the alias of The grandfather:

(8) In 1981, José Barrita, alias El Abuelo (by his hair color), captured the leadership of the bar Boca Juniors, known as La 12. Born in Italy but raised in the neighborhood of La Boca, incorporated many fans to The bar, growing exponentially the number of its members. During this period, the sources of funding for the program were expanded. To the raffles between associates and the contributions of the leaders, is added the collection for the parking of cars in the streets adjacent to the stadium in the days of games in La Bombonera. In addition, some famous members of La 12 begin to be hired as staff of the club, exercising different trades. During his first years in command of the bar, Barrita led violent clashes with partialities of other clubs, leaving like balance 5 dead and one hundred wounded. In 1994, in an ambush to some fans of River, they assassinate two followers of the Millionaire club, fact by which several barras of Boca were condemned to prison. Later, Barrita died, apparently attributed to pneumonia, although his death was never clarified.

For me the right word is the fandom... the fandoms. It is not to talk about barras bravas, that is a misnomer created by the bad journalists. With that expression they fatten the minds, they take them to another side, they make them to say barra brava, for example. [...] Then here appeared that figure, but for the folklore of soccer, barra brava is the fandom. Because the fandom of Argentine football are passion, abnegation, love to the t-shirt. This is as Discépolo said: “A club without a fandom is a club without a soul”. And the most important thing is to put music to the stadium, drums, canticles. They forbid the drums without realizing that they just put music to the stadium. (In Alabarces, 2012, pp. 63-64)

Barrita points to two important issues: first, he attributes to a part of journalism (the “bad journalists”) a misuse of the term “fan”, replacing it with “barrabrava”: the media are its creator. That is, Barrita perceived himself as a member of the fandom, not a barrabrava. Secondly, it folklorizes in a sort of mimicry between barrabrava and fandom. Finally, he recovers the carnivalesque - “to put music to the stadium with drums and canticles” - in football, appealing the legitimated rhetoric of the passion rooted in the ‘90 as a brand that distinguishes the true football fan and the unique feature that can guarantee his survival.

On the other hand, Fernando (32), associate, fan and member of the “Javier Saviola” branch of Berazategui suggests some further details:

“A fan is not the same as an associate, nor is a barra someone who is not. In a stadium you immediately realize that. We (the members of the branch) are first fans and then associates. I explain this to you because there is a percentage of people, of course lower, who is an associate of the club to play some sport and does not necessarily like football. Then you cannot say that those are fans. [...]Fans are us, who come always to see River. Watch it, also the one who follows it from his house with the television, because River has fans all over the country [...] that does not make them more or less passionate”.

Our interviewee points out a distinction between “fan”, “associate” and “barrabrava”. That is to say, an ID card would not grant a person the label of a fan, but rather a series of behaviors and feelings shared with a larger group: “a fan is always the one that is there.” On the other hand, a differentiation could be established with the barrabrava, whose relationship with the club is built on an economic interest, since it refers to “the one who is grouped by the club, who lives on the favors of the club, the one whose micro is paid, the tickets and give him money. [...] If you live from the club, you are barrabrava and the club does not interest you at all. [...] The fandom are the kids, those who go in front, that follow the club everywhere, no matter if they pay you the micro or not” (testimony collected from Alabarces, 2012: 92-93). Their interest is in their own history, that is, the personal. In this definition disappears the emotional contract with the club and “the colors”, to be summed up by an economic contract.

Walking through the central hall of the stadium, Raúl (46), a member, fan and member of the “Norberto Alonso” branch of Baradero, shares a similar definition of what it means to be a fan, and in particular,

The fan, above all things, is faithful. That fidelity or love is only experienced when you are, you group and always encourages. No matter the heat, the cold or the rain. What the River fan has is that historically had paladar a black taste (demanding) with the soccer that he unfolds. This club stands out for having had elite players (referring to the sports level) and we got used to the good game. Then, when you have a bad streak, there are people who stop coming to the stadium. [...] I think those are not River fans, they are result and success fans. What’s more, I venture to say that the descent changed our minds to more than one. To have endured that year in the B marked a break in every sense, beyond the gastadas of the bosteros. We all reflected and appreciated a little more how important it is to come to the Monumental or follow it wherever it plays. The descent made us more fans.

Here, the idea of overcoming short-term adversities is valued and reiterates (the climatic factor, the distances) as a primordial aspect to reach the fan category. In turn, we observe that, according to the interviewee, a historical sporting result (9) impacted on the canons of the riverplatense, granting him a greater consideration to the role of the fan and his constitution as such.

(9) On June 26, 2011, River Plate descended to the First National B, second category of professional football. Reached the promotion again on June 23, 2012.

However, we also find a more romantic look at the constitution of the fan that is not limited to the strictly passionate. Alfredo (78) is a lifetime associate and tells us about a style or hallmark of play:

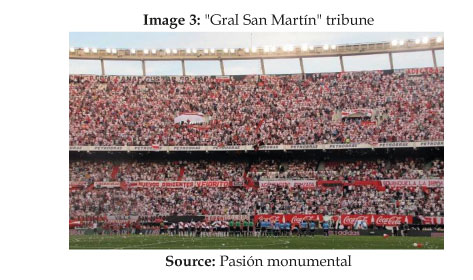

Being a fan of River means to be a lover of “good football”, the one that everyone likes, wins, likes and trashes (we see a flag with that inscription – To win, to taste and to thrash - in the “Gral. San Martín Alta”). [...] Historically we are the club that more championships achieved in the country, setting up offensive teams with players of an exquisite technique and fair play. I can assure you that I saw the best on this court. [...] Being a fan of River is to have that taste, which enjoys the showy display [...], almost unique and is the riverplatense ADN, a trademark. [...]. If you look at the covers of El Gráfico or any other sports magazine you will find that trademark. [...] Independiente was also characterized by that style in other decades. The one who does not like it then he is not a River fan and does not know how to appreciate good football.

Here is evidenced a series of requirements or characteristics that should meet anyone who considers himself a River fan. There is a perception of “good football” linked to the offensive strategy of play and players with a high technique: all this gives rise to the “riverplatense DNA” mentioned by Alfredo, a trademark for both the rivals and the media. In this sense, inherent or “essential” aspects are detected in the construction and socio-cultural configuration of the fan.

Other collected testimonies (10) refer to the physical or biological question, from expressions such as “if you are a fan of River you wear it on the skin” (a young man shows his forearm tattooed with the shield of the club) or “ you carry River in the blood”. Tattoos alluding to identity elements such as the shield, the stadium or big idols of the club are common currency.

(10) Testimonies for supporters in the vicinity of the stadium on March 23, 2014 in the pre-match between River Plate (2) and Lanús (0) in the framework of the ninth date of the Final 2014 Tournament.

We can infer that we live surrounded by “show football”, where some live from it and many more live in it: “we live verbalizing it, talking about it and its avatars” (Antezana, 2003). When we say “some” we refer to the so-called barrabravas, who, following the voices of our interviewees and academic research, have an extra attribute: the endurance. The distinction of these subjects lies not only in the relationships and personal, economic and political interests that they maintain with the club, but in their ability to endure, which is nourished by a series of characteristics of their own.

2.2. Endurance and the other: (i)legitimate use of violence

Identities are constructed not only in opposition to another, but also within a certain finite number of possible options, which calls attention to “a multiplicity of voices and social positions that allow, for example, that the explanation of an ethnic difference can Be described through cultural denominations “(Green, 1995: 165-186).

All of us summon to a them absent and ghostly. It implies, then, the existence of a dialectical tension between a subjective and an objective dimension, since “identity is something that is disputed and with which strategies are proposed, it is both the mean and the end of politics. It is in question not only the classification of individuals, but also the classification of populations “(Jenkins, 1996: 25).

In this way, we can establish that without this rival is the confrontation that does not exist, and with it “the game of identifications that gives it meaning” (Ferreiro, 2003: 62). At present we are in the presence of the spectacle soccer, in which it is necessary to emphasize that there the spectators are also actors. As Antezana states, “show football happens on and off the court. By means of performative verbalization, this spectacle is practically uninterrupted and, without a doubt, multifaceted” (2003: 87-88). The spectacle of football violently happens, too. Antezana himself recognizes a differentiation in the publics or actors who attend the stadiums: “There are highly specialized actors in that part of the game: the barras bravas, for example and, of course, the public forces of order” (2003: 88).

The coparticipation of the actors would be based on the democratic character of the game, in the sense that anyone, regardless of their social determinations of origin, can access, through football, the economic wealth, in short, the recognition related to the social spheres of the power or powers in force. As Bromberger points out, picking up Ehrenberg’s (1992) proposals:

The popularity of sports lies, to a large extent, in its capacity to embody the ideal of democratic societies, showing us, through its heroes, that “no matter who, can become someone”, that status is not acquired from birth but they are conquered throughout their existence. (Bromberger, 1998: 30-31)

In soccer we can recognize both particular cultural identities and meta-identities. Perhaps something that happens there could, if not extrapolate, at least approach the aforementioned debate. There is a certain consensus today in assuming identities not as essential or transhistorical attributes, but as a system of relations and representations. In such a measure, identity is processual and dialogical: that is, it is constructed and reconstructed in social praxis from the relation of alterity that a defined social entity has with other similar entities, an opposition that “usually occurs around to both material and symbolic resources that are necessary for the existence and socio-cultural continuity of those involved “(Almeida, 1997: 175).

At the same time, football expresses, condenses, makes visible and accentuates differences and regional or neighborhood antagonisms. In the case of River-Boca, we have observed a duality-rivalry that emerges in the geography of the Rio de La Plata, where the course of the identity construction of each one responded to diverse social, political, economic and cultural contexts:

Regions, rather than a mere reflection of geographical and economic structures, are constructions of historically determined social agents. In other words, these are collective political projects, more or less developed according to the case, in which objective determinations are processed according to the cultural heritage of the group and the specific historical circumstances that circulate to it. (Maiguashka 1983, p. 181)

Regions, therefore, are not something given that they remain immutable and invariable with the passage of time: on the contrary, they are the product of a particular historical construct given in a given geographical space, which makes them different from each other. The region is an imagined and imaginary community such as the “nation” in terms of Anderson (1993), although it can be said that because of its geographical scale and the greater visibility of its territorial substratum, “the region is closer to the basic social exchanges and, therefore, is less anonymous and less imagined than the latter “(Giménez, 1999, p. 4).

From a sociocultural point of view, football is a festive practice that generates processes of identity and recognition mechanisms. We must understand it from a symbolic logic, “as a catalyst for social, regional, national and continental identities” (Ramírez Gallegos, 2003, p. 107). Soccer identities are articulated today in tribal terms, and this articulation is manifested in the fandoms, in relation to an atomized territory. According to Alabarces, this territory is defended through the practice of endurance, where football is built as a propitious arena in which you can, through violent actions, test the masculinity.

Archetti (1985) argues that Argentine sympathizers are actors in the football show, who through their action not only put at stake the prestige of the club but also the masculinity of the participants. For this author, Argentine football is a strictly masculine space, where men and projects of men, adolescents and children, try to build an order and a manly world. This construction of orders is transformed into moral discussions, establishing boundaries between what is allowed and what is prohibited, between positive and negative attributes of what is ideally defined as masculine; moral discourses that constitute distinctive practices.

Violence can then be interpreted as “a cultural construction that has different physiognomies according to the practices and representations that nourish it with meaning” (Nordstrom and Robben, 1995), an action with the same meaning as other social actions. In this way, violent practice is socially constructed according to the cultural parameters of its practitioners. The physiognomy of violence in football takes on different nuances according to the countries where the events occur: “in the Argentine case it has its own characteristics, different and distinctive of the peculiarities that the same phenomenon has in the rest of the world” (Garriga Zucal, 2006, p. 40-41).

Following this idea, the members of the barra brava conceive the endurance as the main symbolic good that is disputed in the context of football. This symbolic capital allows distinguishing between man and non-man, according to who owns it:

A barra brava, seen from the standpoint of the militant or active fans themselves, is defined by an economic or political relationship (or both at the same time) that maintains organically with the club or with part of its leaders. [...]. It is a group of actors, identified to themselves as fanatical fans of the club, but who are classified by the rest of the fans - and by the sports, political and police leaders that contract their services - as a form of instrumental relation with the soccer, while the central objective is a particular and economic interest”. (Alabarces, 2012, p. 66).

The latter confirms what we said earlier about who they are and whose main characteristic is that they are not authentic or true supporters. In clubs there is a hard core, militant, that organizes activities both inside and outside the stadium. Also the spaces, the trips, the making of flags, etc. But there is a larger goal, transversal to all these: the political participation in the institutional life of the club.

All this is established around the affective core, that is, the love for the team, the club, the colors / the neighborhood; This nucleus exercises a greater level of violence in its confrontations with opponent fandoms, the police or the same companions of tribune. We will call this group barras. (Alabarces, 2012, p. 67)

From the field work carried out characterizations or definitions that correspond with the latter emanate, contributing also the quality of associates of many of them and the historical complicity with the managers:

Here it is known that Los Borrachos del Tablón (11) as the rest of the other bars are members of the club. That’s why I told you that associate can be anyone, but not fans. Those guys are not fans, they’re mercenaries who fill their pockets by pressing and at the expense of the club. How can it be explained that guys involved in any incident there is do not have their cards removed or are thrown out? Connivance and complicity with the leaders of the moment, the police and the justice. Not only the incidents that appear on the radio or television, but those that are not known as well. I was on the day of the quinchos (12) battle and it was a craze. It was terrible, a savage act, you realized that people were very scared because the movement of people fell too much from that moment.

(11) It is the name with which it is known to the barra brava of River Plate. Since 2008, the leadership is shared by Eduardo Joe Ferreyra, Héctor Caverna Godoy and Martín de Ramos Araujo. The first aimed at political issues, the other two performers of power in the rostrum. On the other hand, the faction of the Banda del Oeste, which is composed of about 250 bars that were displaced from the crowd after the murder of Gonzalo Acro (August 9, 2007). They also formed part of the official bar in the 1990s and concentrated an important power in the first five years of 2000. In 2014 they obtained the support of Los Patovicas of Hurlingham, a group led by Darío Velardez, alias Toti and head of the bar Sportivo Italiano. See: <www.infobae.com/2014/11/26/1611209-river-who-who-who-the-barra>. Accessed January 22, 2016.

A priori, would be established a network of relationships that exceed the strictly sporting or passionate if the term fits. This semblance of the barrabrava is endowed and articulated in a violent behavior that, according to Alabarces, is exhibited as a fundamental symbolic capital. That is, violence is a central component that, based on the ethics of endurance, implies a legitimate use of it.

Tell me to which tribune you go to and I’ll tell you what kind of fan you are

In the same way, this logic would allow us to observe how a stage of a soccer stadium is organized or schematized, in other words, to reproduce the spatial distribution in the popular tribune:

In clubs where there is a barra, it occupies the space and symbolic center. Every practice in the stadium must have its organization and authorization. [...] A barra is always surrounded by a second militant nucleus, follower, fanatic, organized purely around affective relations. It is what we call militant fans, a term of ours and not accepted by them. These fans are organized in one or more groups, usually identified by particular flags that refer to a neighborhood or simply a fancy name. These groups reject economic links, although they would never despise a free micro. Another difference is that they occasionally use firearms. And finally, in the space and symbolic periphery, there is the rest of the spectators. In this sector there is everything. [...] All of them, almost in unison, are convinced that violence is a barbarity, a thing of drug addicts and drunks, except when the central protagonist is their own fandom “(Alabarces, 2012: 69).

Some issues to highlight. Los Borrachos del Tablón have emblems and flags that allow them to be identified during the games of River Plate, in particular one that shows the inscription of the barra with the territory of the Malvinas Islands in the center (this will be subject of discursive analysis in the following chapter) And is usually located in the “Sivori Alta” (below the stadium screen), on Av. Leopoldo Lugones.

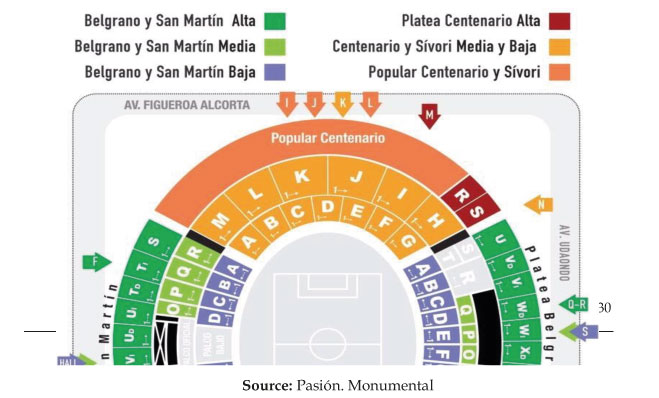

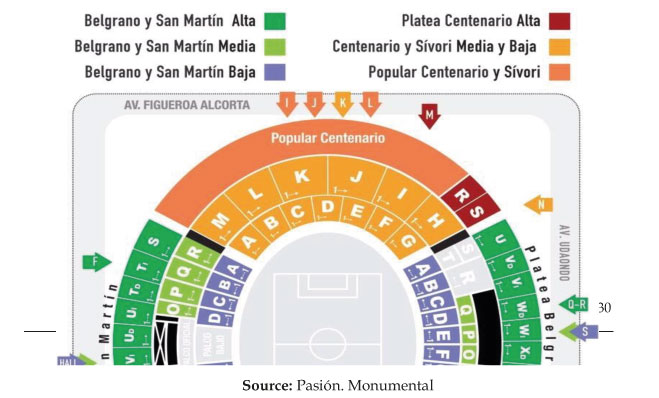

However, we find certain fissures or inconsistencies in this preliminary spatial classification fan / tribune proposed by Alabarces. As for the distribution of the “particular flags that refer to a neighborhood or simply a fancy name,” these are located in all sectors of the stadium, they are not exclusive to the vicinity of the sector of the barra. In other locations, that is, “Gral. San Martín”, “ Centenario” and “Gral. Belgrano” (both in public and popular stalls) those that refer to neighborhoods, localities or bands are also exhibited. In the “Sívori” stand, for example, it is usual to observe “San Justo”, “Garín”, “Florencio Varela”, “Floresta”, “Villa Elisa”, “Haedo” and “Retiro”, among others.). In the case of the “Centenario” tribune there is something similar with flags of other localities and supporters’ clubs: “Mataderos”, “Villa Crespo”, “Rafael Calzada” or the “Ariel Ortega” supporters’ group (Image 2). Finally, in the sector “Gral. San Martin “:” Villa Fiorito “,” Solano “,” Ramos Mejía “or” Morón “(Image 3).

The following graphics indicate the location of the stadium as well as the distribution of the different sectors with their respective headers and locations.

If we refer to the images, according to the spatial disposition that the author presupposes with respect to the so-called “militant fans” and the other actors, two possibilities emerge: the first, that the militant fans are located in all the tribunes and not only in proximity to the barra brava. In this case, the barra would occupy all the stands equally, contrasting with the distribution of the public raised in the scheme of Alabarces, by which it is in the main sector and more visible (or in its heart), which is usually the popular one. If Image I is observed, there is no flag near the perimeter occupied by Los Borrachos del Tablón in the zone of the “Sivori Alta”; On the contrary, only the cloth that makes reference to that radical group. The second, that the fans that attend with flags - or at least not all of them - are militant supporters in the terms that the author exposes, but that they fulfill a representative local or regional function. In this sense, its members also do not recognize having had any direct contact with the members of the barra:

The flags of the branch identify us as members of a larger group or group that is River as a club. If you look, most of them are from localities of the province of Buenos Aires, they have their presence in the stadium. Our branch never had contact with some barra, in fact we come to the matches in own combis or private cars. We never went to a paid micro because we could not if we wanted. That type of transport is exclusive of them that mobilize in that way.

Natalia (29) is part of the “Norberto Alonso” branch of Baradero and his testimony is opposite to the direction given by Alabarces: the flags that refer to localities or neighborhoods have a double representative character or belonging, that is, the club (River ) and its region of origin (Baradero). She is not alone in pointing out this question, since her partner Héctor (41) agrees with her and expresses which place and role the affiliates occupy in the identity of the club, as well as in the framework of a game:

I do not know what a “militant fan” is. More than twenty years ago I have been coming to this court and the differentiation was and will remain the same: the barras, the associates of Capital (Federal) that have the stadium at hand, those who come from Province and those who come from time to time or the team is doing a good campaign. [...] The barrabrava always occupied the same place, in the head over there (she indicates the sector of the “Sívori Alta”), as it says, without asking for permission [...] they appropriated it. [...] The clubs or branches bring their flags as a way to say “here we are”, “Baradero is from River and is present”. [...] We have nothing to do with Los Borrachos del Tablón, neither before nor now. They mobilize with their paid micros, just like the trips to the interior, all paid by the leaders. This happened with (Alfredo) Davicce, (David) Pintado, the unnamable (Jose Maria Aguilar), the other unnamable (Daniel Passarella) and now with (Rodolfo) D’Onofrio. We (the branches) do it by our own means. In addition, we bring many guys and people who for the first time can see River and their idols other than on television. It is nice to be able to see that your flag appears in the photo of a newspaper or in a newscast, and better yet, that a player of the team is native of your city.

These stories overturn the cartographic accuracy of the fan / tribune map that Alabarces supports. There is no correspondence between the militant supporters characterized by the author and the bearing of flags. As many of these as their owners do not have any connection with Los Borrachos del Tablón or other dissident groups in the barra. So far, the only possible difference to establish is, on the one hand, the authentic ones, those who express a genuine and uncorrupted sentimental affiliation with the club and “reproach the economic interest” (Alabarces, 2012: 70), and on the other, the bars, subjects that profit from the economic and material resources of the club, giving preference to their personal aspirations instead of the affective ones.

2.3. Some have endurance, do others “look and imitate”?

Understanding the logic of violence in football and its historical background from various significant events (in our country and Great Britain) is the starting point to better understand a broader phenomenon: the construction of football identities and the implication of the violence.

One of the central aspects of this thesis has been to problematize and to analyze the ways in which this process is developed, which, of course, is not unidirectional and is crossed by subjectivities and multiple disputes. In this journey, and more precisely, the search to understand the behaviors of the subjects attending the River Stadium, we are faced with the ethics of endurance proposed by Alabarces, according to which “endurance organizes all practices. It is not just a question of the barras, but also peaceful fans / non-barras and peaceful spectators, who euphorically chant ‘this is the fandom that has more endurance’, proud of their membership in a male, aggressive and macho collective. They are paid because they have endurance” (2012: 71).

Previously we observed the inconsistencies that the scheme presents that this theory raises regarding the scheme or public disposition in the different sectors of the stadium. Although the barra brava occupies the head with greater visibility, the classification does not coincide with the rest of the actors, for example, the so-called “militant fans” and their characteristics.

At the same time, the ethic of endurance “is organized as a basically moral system... that has rhetoric, that is, a vocabulary and a language that allows us to understand it” (Alabarces, 2014: 157). If we remember the murder of Raúl Martínez at the hands of fans of Quilmes in 1983, the “endurance” is an emerging term that is framed in the ‘80s:

To endure refers to being a support, to endorse. Also to be supportive. Hence the idea of making the endurance appears initially. The expression alluded to the support that peripheral groups or friendly fans offered in confrontations. In the football culture of the last ten years, this notion began to be loaded with very hard meanings, decidedly linked to the putting into action of the body. (Alabarces, 2012, p. 72)

Enduring, then, contemplates a fundamental role of corporeality, since it is neither more nor less than “putting the body”. But this act also implies a share of physical violence. You do do not endure if the body does not appear as the protagonist, enduring a damage, be it blows, wounds or, more simply, colds. insolations, etc. This logic of practice consists of a moral universe according to which to defend the honor, tradition, territory and colors of the club is a task of males that must be executed with the body from a series of especially violent practices: the combat or the fight. The endurance is a way of naming the code of honor that organizes the fandom collective and many of its practices. Defense of honor involves the combat, the duel or the revenge. The endurance is oriented toward the other, that is, it is displayed in front of the other, and competes with it to see who has more endurance

The endurance thus becomes, in recent years, a rhetoric, an aesthetics and an ethics. It is a rhetoric because it is structured as a language, as a series of metaphors, and refers to an aesthetic because it is explained as a form of plebeian beauty, based on a type of body radically different from the hegemonic and accepted.

It is not the type of bodies that appear in the television or in the cover of the Caras magazine: they are robust bodies, big ones, where the scars are emblems and pride. An aesthetic that has much to do also with the carnivalesque, display of disguises, paintings, flags and even fireworks. And it is an ethic because the endurance is above all a moral category, a way of understanding the world, of dividing it between friends and enemies, whose difference can be settled with death. An ethic, in short, where violence is not thought but recommended. (Alabarces, 2012, p.73)

The male bodies characterized by this theory emphasize in a non-hegemonic stereotype and their corresponding properties:

The model of the fat is among the fans a legitimate model, as these have more endurance. [...] This enduring aesthetic demands that the masculine bodies also bear scars and marks. Thus they testify to the participation in the engagements and, consequently, the legitimate masculinity of the fighters. [...] In addition, the fight must be on equal terms, at close quarters, without mediations. [...] To endure is also translated into resistant bodies that tolerate the consumption of alcohol and drugs. (Alabarces, 2012, p. 76-77)

In this way, we are faced with an organized culture that gives meaning and legitimacy to violent practices. This entails the cause problems entirely with the violence in all its dimensions and implications:

–Violence is every day. It occurs within a framework of everyday life and, at the same time, as a permanent and always visible data. It is also observed from the macro level, which is structured within social relations.

–Violence is adrenaline. It is pure drug; it is alteration of an order that is rejected because no benefit is perceived. It is pure excitement and pure desire; And the practitioner becomes addicted.

–Violence is collective construction. Body contact grows as a guarantee of group existence.

–Violence is a construction of power and, in short, allows it to be accumulated and exercised with greater force.

–Violence is “legitimate.” This does not mean legal, but relies on consensus.

–Violence as visibility. It becomes visible before the rest of society, before those who qualify the fans of misfits, before those who exclude them.

In short, according to this ethic violence is effective, achieves all its objectives, allows to accumulate power, guarantees visibility, allows to build collectives. It is useful, functional and rational. Violence does not mean any irrationality; on the contrary, it is rational, predictable and planned; And it is, therefore, explicable and avoidable that it possesses political edges.

In this way, violence implies a claim. It expresses in each endurance and confrontation the presence of that which was excluded. In the overflow they demand a new social inclusion. Of course, the concept of exclusion exceeds the socioeconomic limit. They are actors expelled from education or work in other cases, but massively are also actors expelled from a democratic account that speaks of a just society.

In addition, the fandom cannot help but have endurance: “the fandoms see themselves as the sole custodian of identity, as the only actor that does not produce economic gains but produces symbolic and passionate gains. [...] Fans can only propose the defense of their benefit of passions and their production of pure feelings “(Alabarces, 2012, p. 88-89).

The central point is that Argentine football culture has become a space where violence becomes a style, a way of acting, a way of understanding life and marking the relationship with the world, and where an adequate interpretation of the subject has to place violence, in addition, in an historical perspective. To quote Archetti, Argentina’s football culture has been a mix of tragic and comic elements, an oscillation between the violent and the carnivalesque, where the comic elements would have predominated in the classic Argentine football era, being progressively displaced by the tragic elements in the last three decades.

Thus, violence presents itself as a practice that cannot be rejected, but, on the contrary, it is valid: it is closely related to honor and even results obligatory. In other words, some or a few - the barras - are the owners of the endurance. In the field work carried out, some questions were detected about this situation: is it transversal to all the fans? To what extent does the culture of endurance explains the behaviors and conducts of the public? Can we talk about a monolithic and homogenizer device? What role does the habitus posed by Pierre Bourdieu plays?

2.4. Old people without endurance

The dimension of the popular is visible in the field of football because it is a trans classist space, operated for new identities and in the unequal struggles (in terms of material and symbolic goods). Thus, the current national football culture would be the result of a transformation: the passage from an ethics of the game as a “gentlemen’s thing” to another understood as “men’s thing”, that is, the current stage. Moreover, if we refer to the ethic of endurance, it would no longer be men, but machos, as machos as “having codes and to endure” (Alabarces, 2008). This ethics involves an inversion of values such as mutual respect, diversity and non-discrimination, between people.

From the numerous occasions that we attended the Antonio V. Liberti stadium a wide spectrum of fans was recognized. Establishing a faithful and precise classification of them according to various factors - age, gender, occupation, social class, among others - would have required a longer period of time and work in the field. However, the implementation of another formula or evaluation criterion yielded significant results. Basically, they were grouped according to their formal / informal link with the club: fans, associates, barra bravas and spectators. Within the second group, we collected a set of relevant testimonies related to our questions. We can even speak of a subgroup within the item “associates”: the lifelongs.

The accounts of Alfredo (78), Luis (78), César (76) and Ricardo (80), hereafter referred to as the lifelongs (13), contrast, or rather, are at the antipodes of the ethic of endurance. This has been placed in the center of the scene in the academic studies linked to the axis soccer-violence. However, does the endurance “govern” across the behavior of all audiences attending football stadiums? Maybe it is the only type of behavior possible?

(13) With them I shared a long conversation in the club’s confectionery, we toured the museum and the central ring of the stadium. Between the four they add more than two hundred years of associates.

From the dialogues held with “the lifelongs” other ways were evident: there were factors and relevant aspects that were outside the idea of Alabarces in relation to endurance. They stated again and again that they were not perceived as producers and reproducers of violent and discriminatory practices:

I come to see River from the time of La Máquina (14). Almost always with my father or grandfather. The rivalry with Boca existed and will continue to exist. What I notice, is that the values and ways of feeling football changed. I never sang the barbarities that are said now. All these things came with the troublemakers up there (points out the tribune and the space occupied by Los Borrachos del Tablón). They do a lot of damage to football, to the fans. They hit people. [...] In the best of cases they fight with the police or between themselves, if they do not end up killing someone.

(14) La Máquina is the name of the formation of River Plate that achieved eight championships in the decade of the 40: First Division (1941), Glass Adrián C. Escobar (1941), Glass Doctor Carlos Ibarguren (1941), Glass Aldao (1941), First Division (1942), Cup Doctor Carlos Ibarguren (1942), First Division (1945) and Aldao Cup (1945). He was considered by the specialized press as the best team of his era and one of the best in the history of world football. Juan Carlos Muñoz, José Manuel Moreno, Adolfo Pedernera, Ángel Labruna and Felix Loustau (although Aristóbulo Deambrossi, Carlos Peucelle and Alberto Gallo were also regular headlines). Source: official site Club Atlético River Plate. Online: <www.cariverplate.com.ar/history>. Retrieved on January 23, 2016.

Although the words of Caesar have a certain linearity, it makes a clear difference between them / us: they, the barras, the violent, the impure or polluting of football; we, true fans, respectful of rivalry. What marks that difference between each other? Does not everyone recognize themselves as River fans? Evidently, “the lifelongs” are not crossed or self-perceived as members of the culture of endurance. The “fandom” forms a “community” of belonging, which is defined as being the possessors of the “endurance”, those who fight (Alabarces 2004, Garriga Zucal 2005, Garriga Zucal and Moreira 2003). This symbolic good brings them together and makes them different. The verb to endure becomes noun, thus building communities defined by practice; Those who have endurance and those who do not have it. This establishes a difference between those who dispute the endurance and those who do not share those forms of distinction. So “the lifetimes” have no endurance? Does this leave them drastically out of the football community?

This type of culture manifests itself as a totalizing, monolithic and generalizing conception that fails to spot other audiences outside of those who endure. To consider it a socio-cultural law or regulation that governs the field of football is a biased position that leaves out and dislodges from all legitimacy those fans or audiences that are not recognized as subjects immersed or crossed by that logic.

For some reason, our interviewees do not feel part of the same group as the “crooks up there”. In this sense, the concept of Pierre Bourdieu’s habitus contributes another edge to the problem. According to the French sociologist, the habitus comprises the set of generative schemes from which subjects perceive the world and act on it. These generative schemas are generally defined as “structured structuring structures” (Bourdieu, 1980: 172); Are socially structured because they have been shaped throughout the history of each agent and suppose the incorporation of the social structure, of the concrete field of social relations in which the social agent has conformed as such. But at the same time they are structuring because they are the structures from which the agent’s thoughts, perceptions and actions are produced. This structuring function is based on the processes of differentiation in terms of the conditions and needs of each class. This makes the preponderate efficacy of cultural practices assumed as their own in respect to which they are not act as a sieve (selection criterion) of hegemonic culture (arbitrary, social and historical recognition of its value in the field of the symbolic), According to Bourdieu, culture matters as a subject that is not foreign to the economy or politics.

From this Bourdian concept, structured structuring structures are categorically visible in Luis’s statements:

In my house I never heard a dirty word or insult. If for some reason it happened, I cannot explain the mess I was in with my father. On the court these things are commonplace, and when I come with my grandchildren, Tomás and Franco, I forbid them to sing or repeat these barbarities. I see many parents who come with their children and do not realize that the boys, without realizing it, copy that; the bad thing about football. The education they have at home is seen here on Sundays. Times changed and that shows.

Education and the family are two words and institutions that are reiterated in the narratives of the interviewees. Contrariwise, none of them is taken into account or considered by the endurance. Returning to the idea of Bourdieu, one of the fundamental dimensions of the habitus is its relationship with social classes and social reproduction. If it is acquired in a series of material and social conditions, and these vary according to the position in the social space, one can speak of “class habitus”. These class habitus, in turn, are systematic: produced in a series of social and material conditions of existence - not to be grasped as a sum of factors, but as a systematic whole - linked to a certain social position.

In this way, there would be a series of schemes generating practices common to all biological individuals that are the product of the same objective conditions. Given the impossibility of segmenting or identifying who would be the subjects included in the culture of endurance (although it is aimed at universalizing them), one can identify the “class habitus” of “the lifelongs”: River Plate lifetime members, retired and professionals, inhabitants of the North Zone of the GBA (specifically Olivos and Vicente López) whose practices and speeches are rooted in respect for the adversary and, mainly, a marked socio-cultural opposition to the barras.

2.6. Do they have no endurance?

Walking through the corridors of the Monumental, it was one of the questions that I asked to “the lifelongs”: what does it mean for you to have endurance? The four sketched similar responses but differed in relation to the definition or idea proposed by Alabarces.

I do not know what they mean by endurance. I imagine that to endure the fights and blows with the fandom of the other clubs to put to a test who are the gutsiest. We are fans, associates and we have a very deep feeling with this club. Sometimes many associates pushed by fervor sing things that neither they believe they are capable of doing, like killing someone or beating the police. These issues were naturalized not only here in River and with the fan of Boca, but in all stages. That to see who has the biggest fandom and who are the most macho happens in all Argentine football regrettably. Think that we in the 50s or 60s came in a suit or shirt on the court; all the public. That changed totally, like society and values.

In other words, but pointing to the same fact, these life associates of River recognize dissimilar and complex social fabrics in the public that attend the stadium of Núñez. In this sense, it could be established that both those who endure and those who do not, maintain a clearly subjective bond with the club. On the other hand, Alabarces affirms that

There are no misfits, wild, irrational, animals. There are no exceptions, no arbitrary or hazardous phenomena. But that everything belongs to a minute, complex, absolutely recognizable and understandable logic that is called “Argentine football culture”, within which violence is the norm, not the exception. Violence is the pattern that structures the entire Argentinian football culture. (Alabarces, 2011)

However, from the testimony of the interviewees, it is evident that this culture proposed by the author is biased, pretentious (in terms of homogenization) and monolithic, where there is no place for subjectivities, reducing it to a large mass that produces and reproduces a logic of some, without asking or questioning whether they are willing to endure. It is here that one of the fundamental dimensions of the habitus means a contribution to the question: its relation with social classes and social reproduction. If the habitus is acquired in a series of material and social conditions, and if these vary according to the position in the social space, one can speak of “class habitus.” That is, there would be a series of schemes generating common practices to all biological individuals that are the product of the same objective conditions (Bourdieu, 1980).

These subjects who endure and make, from their logic, a legitimate use and exercise of violence could be understood as an objective reality. In contrast, there is also a subjective reality, which is the appreciation made by the various subjects of the same (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). That is, society is experientially experienced by the subject. In the same way, River fans (in this case) construct various subjective realities in terms of identity. That is, to account for objective and subjective realities (Berger and Luckmann, 1966), where the culture of endurance is not automatically constituted and “governs” the behavior of fans, but it is possible to find other socio-cultural behaviors and modes of expression in subjects.

To establish that the ethics of endurance operates with such success or efficiency, as also internalized generically, would imply overestimating it, at the same time underestimating the subjective identity configurations associated with soccer.

REFERENCES

1. Alabarces P (2004). Entre la banalidad y la crítica: perspectivas de las Ciencias Sociales sobre el deporte en América Latina. Memoria y Civilización. Anuario de Historia de la Universidad de Navarra, 7.

2. Alabarces P (2006). El deporte en América Latina. En Enciclopedia Latinoamericana. Río de Janeiro: CLACSO.

3. Alabarces P y otros (2006). Hinchadas. Buenos Aires: Prometeo.

4. Alabarces P (2008). Fútbol y patria. El fútbol y las narrativas de la identidad en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual editora.

5. Alabarces P (2012). Crónicas del aguante. Buenos Aires: Capital intelectual.

6. Almeida J (1996). Polémica antropológica sobre la identidad, en Identidad y ciudadanía. Enfoques teóricos. Quito: FEUCE- ADES- AEDA.

7. Almeida J (1997). Identidades múltiples y Estado unitario en el Ecuador, en Identidad nacional y globalización. Quito: ILDIS.

8. Antezana L (2003). “Fútbol: espectáculo e identidad”, en Alabarces P, (comp.) Futbologías. Fútbol, identidad y violencia en América Latina. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

9. Archetti E (1985). Fútbol y ethos, en Monografías e Informes de Investigación N°7. FLACSO.

10. Archetti E (2003). Masculinidades. Fútbol, tango y polo en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Antropofagia.

11. Bourdieu P [1980] (1991). El sentido práctico. Madrid: Siglo XXI editores.

12. Bourdieu P (1996). Cosas dichas. Barcelona: Gedisa.

13. Bromberger C (1998). Football, la bagattelle la plus sérieuse du monde. París: Bayard.

14. Conde M (2006). La invención del hincha en la prensa periódica, en Alabarces P (2006). Hinchadas. Buenos Aires: Prometeo.

15. De-Vedia M (1998). La pasión que despierta el fútbol tiene dos caras, en La Nación. Recuperado de http://www.lanacion.com.ar/97795-la-pasion-quedespierta-el-futbol-tienedos-caras

16. Frydenberg J (1997). Prácticas y valores en el proceso de popularización del fútbol, Buenos Aires 1900-1910, en Entrepasados. Revista de Historia, Año VI

17. Frydenberg J (2011). Historia social del fútbol: del amateurismo a la profesionalización. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI editores.

18. García-Ferrando M (1990). Aspectos sociales del deporte. Una reflexión sociológica Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

19. Garriga-Zucal J (2011). Nosotros nos peleamos. Violencia e identidad de una hinchada de fútbol. Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros.

20. Garriga-Zucal J (comp.) (2013). Violencia en el fútbol: investigaciones sociales y fracasos políticos. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Godot.

21. Giménez G (1999). Materiales para una teoría de las identidades sociales, en Valenzuela J, (comp.). Decadencia y auge de las identidades. México: Colegio de la Frontera-Plaza y Janes.

22. Green N (1995). Classe et ethnicité, des categories caduques de l´histoire sociale?, en Lepetit B, (1995). Les formes de léxperience. Une autre histoire sociale. París: Albin Michel.

23. Hall S (1997). Cuestiones de identidad cultural. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

24. Jenkins R (1996). Social Identity. Londres: Routledge.

25. Maiguashca J (1983). La cuestión regional en la historia ecuatoriana, en Ayala M (comp.). Nueva historia del Ecuador. Quito: Corporación Editora Nacional.

26. Nordstrom C, Robben A (1995). The Antropology and Ethnography of Violence and Sociopolitical Conflict, en Nordstrom C, Robben A (ed.). Fieldworkunder Fire. Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival. Berkeley: University of California Press.

27. Ramírez-Gallegos J (2003). Fútbol e identidad regional en el Ecuador, en Alabarces P (comp.) (2003). Futbologías. Fútbol, identidad y violencia en América Latina. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

28. Salerno D (2005). Apología, estigma y represión. Los hinchas televisados del fútbol, en Alabarces P y otros. Hinchadas, Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros.