Figure 1. Sexual assaults in Spain.

doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1239

RESEARCH

WOMEN’S SOCIAL ACTIVISM IN THE DIGITAL PUBLIC SPHERE

ACTIVISMO SOCIAL FEMENINO EN LA ESFERA PÚBLICA DIGITAL

ATIVISMO SOCIAL FEMENINO NA ESFERA PÚBLICA DIGITAL

1University of Seville. Spain.

[1] Marián Alonso-González: Licenciada en Periodismo y Doctora en Comunicación Social por la Universidad de Sevilla, donde ejerce de profesora asociada, ha orientado su investigación a campos relacionados con la Comunicación 2.0, el Periodismo 3.0 y los lenguajes multimedia e interactivos.

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes how, after years of apathy towards participation, women have decided to denounce situations of injustice and gender inequality. Social networks have made it possible to interconnect women of different generations, exploiting opportunities for instantaneity, scope, and gratuitousness, emphasizing on important aspects as the fight against gender-based violence and promote gender equality policy. From the perspective provided by the hemerographic reviews, we have analyzed how movements such as #Yositecreo or the 2018 International Women’s Strike have put sexual harassment, assaults, and abuses, to which many women around the world have been subjected to, into de spotlight. Feminist cyberactivism has opened up to forge alliances, to debate and to analyze needs, as well as to agree on inclusive and representative measures, but it has also achieved, thanks to social pressure, great accomplishments such as a new law on sexual freedom or a Royal decree-law that aims to resolve the gender pay gap. However, women still have great milestones ahead to be achieved such as equal opportunities at work and a balanced distribution in leadership positions, measures that, thanks to this collaborative action, are increasingly occupying a more prominent place in the agenda- setting of governments.

KEY WORDS: Social Networks, Internet, Cyberactivism, Feminism, Mobilization, Participation,Networks, Social changes.

RESUMEN

El presente estudio analiza cómo Internet y las redes sociales han permitido interconectar a mujeres de distintas generaciones para, explotando las oportunidades de instantaneidad, alcance y gratuidad, poner el acento en la lucha contra la violencia de género y las políticas efectivas de igualdad. Desde el enfoque que nos proporciona la revisión hemerográfica analizamos cómo los movimientos #Yositecreo o la huelga del Día Internacional de las Mujeres de 2018 ponen el acento en el acoso sexual, las agresiones y los abusos a los que son sometidas muchas féminas en el mundo. El ciberactivismo feminista ha abierto una puerta para forjar alianzas, debatir y analizar necesidades, así como para consensuar medidas inclusivas y representativas, pero también ha conseguido, gracias a la presión social, grandes logros como una nueva ley de libertad sexual o un Real decreto-ley que pretende resolver la brecha salarial. No obstante, las mujeres todavía tienen grandes hitos por alcanzar como son la igualdad de oportunidades laborales o un reparto equilibrado en los puestos de dirección, medidas que, gracias a esta acción colaborativa, ocupan cada vez más un lugar destacado dentro de la agenda setting de los gobiernos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Redes Sociales, Internet, Ciberactivismo, Feminismo, Participación, Nuevas tecnologías, Movilización, Cambio social.

RESUMO

O seguinte estudo analisa como a Internet e as redes sociais permitiram conectar mulheres de diferentes gerações para, aproveitando as oportunidades de instantaneidade, alcance e gratuidade, colocar força na luta contra a violência de gênero e as políticas efetivas de como os movimentos #Yositecreo ou a greve do Día Internacional das Mulheres de 2018 focam no abuso sexual, as agresoes e os abusos aos que sao submetidas muitas mulheres no mundo.O ciberativismo feminista tem criado portas para forjar alianças, debater e analisar necessidades, assim como para negociar medidas inclusivas e representativas, mas também têm-se obtido, devido a pressão social, grandes soluções como a lei de liberdade sexual ou outras para solucionar as diferenças salariais. Não obstante, as mulheres ainda têm grandes desafios por conseguir, como são a igualdade de oportunidades laborais ou uma divisão equilibrada nas posições de direção, medidas que, graças a esta ação colaborativa, ocupam cada vez mais lugares destacados dentro das agendas de discussão dos governos.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Redes Sociais, Internet, Ciberativismo, Feminismo, Participação, Novas tecnologías, Mobilização, Mudança social.

Correspondence:

Marián Alonso-González. University of Seville. Spain. malonsog@us.es

Received: 26/05/2020.

Accepted: 14/12/2020.

Published: 12/03/2021.

Como citar el artículo:

Alonso-González, M. (2021). Womens’s social activism in the digital public sphere. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 154, 133-156. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.150.e1239 http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1239

Translation by Carlos Javier Rivas Quintero (University of the Andes, Mérida, Venezuela).

1. INTRODUCTION

On August 23, 2007, Twitter hashtags emerged. Eleven years after their creation, these virtual tags have become a powerful tool to exchange opinions or ideas, very prominent in social movements, to the point of becoming one of the “most influential signs of the digital era” (Diario de Sevilla, 2018). On average, 125 million hashtags are shared every day around the world, which helps users see what is happening and explore what is being discussed at that moment, according to the company itself.

However, hashtags are not exclusive to Twitter. LinkedIn, Google+, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube are some of the social networks on which these links are used to group updates on a specific topic, giving them the capacity to be an excellent tool to make common problems visible, since they enable citizen empowerment and promote an environment in which any person can consume all the information available on the network fast.

Social networks have made mass communication free and universal, since it allows organizations “an almost permanent contact with their publics at a very low cost and reinforcing the two-way symmetrical model” (Alonso, 2015).

Multiplicity of technologies allows messages, that were previously left out of the communicational circuit, to be known, favoring the emergence of a new concept, cyberactivism, understood as the set of information technologies that enable faster communications in the movement and dissemination of information to a vast audience, to change the public agenda and to make various causes visible (De Ugarte, 2007).

This idea is also shared by Caldevilla (2009), who defines cyberactivism as the dissemination of information as the central node of action, and by Sierra-Caballero (2018), who considers it as a revolt of the imagination in the face of the collapse of the traditional political system.

For her part, Reguillo speaks of technopolitics, the power to make-see or make-believe and how “through this multipolar system, they oblige conventional media to incorporate topics, issues, and information that travel from the web to the streets and vice versa; not a small achievement” (Reguillo, 2017, p.123); a thesis that Tascón and Quintana (2012) share, to whom these forms of activism entail the amplification of messages or the reduction in mobilization costs; since the web’s public space would allow a horizontal and relatively autonomous exchange.

Cyberactivism articulates around empowerment, collaborative culture, free distribution, and access to information, as well as self-organization as an fundamental premise of mobilization (Burgos, 2017), and the feminist movement has known how to seize these opportunities to invite citizens to reflect on the matter and to work for the sake of an egalitarian society.

Social networks became an important tool for communicating issues related to women’s rights and gender equality, allowing local issues to become global matters, gaining prominence as active agents in democratization processes (Della Porta & Diani, 2006; Giugni, 2004).

Cyberfeminism began in the 1990s with the works of VNS Matrix, a feminist artist collective whose activist practice was concerned primarily with women’s role in technology and art. Subsequently, in 1997, Sadie Plant addressed cyberfeminism as a concept of theoretical argumentation in which humans and information theory would find new ways to construct the subject and human identity (Ramírez, 2019). In fact, Plant saw in cyberactivism an open window to end the patriarchal system, which means seeking new scenarios to achieve equal rights between men and women (Gago, 2019, p.12).

Interpersonal networks are not a new phenomenon within the communication field, but it is true that relationships between people have come to change to the point that we can now speak of a participatory culture that transforms the society in which we live (Alonso, 2014). Social movements and civil society have found a space for debate and confrontation of ideas in new technologies, in fact, “feminist networks work at a local, regional, and global level, with online and offline activities, blurring the artificial frontier between both spaces” (Fernández & Rubira, 2012, p.1531).

The increasing presence of women on the Internet has contributed to attracting a “much younger generation of activists, who represent a key target public in the fight against the established stereotypes to achieve gender equality” (Escobar, 2016).

From this perspective, the cyberspace is presented as “an opportunity for feminism to advance in equality, pluralism, and the balanced expression of gender discourses” (Núñez Puente et al., 2013, p.180), and this is due to four basic characteristics identified by Feliciano and Mallavibarrena (2013): massive availability, storage and information creation capacity, its users can be content producers, and the capacity to discuss and share knowledge between them.

Similarly, female theorists such as Haraway (1991) and Kember (2003) point out that technology offers new forms of social relationships online, and, therefore, it allows creating new ties between women in order to prevent the patriarchal system from monopolizing the virtual world. Thus, some works show how the Internet is a space for relationships in which women’s political visibility is possible (Núñez Puente, 2011) and how technological developments become an essential part of change and progress (Gajjala & Ju Oh, 2012).

In fact, in order to strengthen women’s political participation, OECD (2018) recommends three effective strategies which are to guarantee equal access and use of new technologies, to increase women’s capacity to participate in decision-making processes, and to involve different sectors in order to strengthen campaigns and help draw more attention, both globally and locally.

In the face of theorists who point out the counterproductive effect that horizontal communication and the lack of hierarchy can have in decision-making processes (Danitz & Strobel, 1999), Reverter (2009) states that the Internet is a democratic space, free of prejudice, in which female users can express themselves regardless of their gender or sexuality.

Despite cyberactivism opening new roads in the fight to achieve effective equality between women and men, there is still an important handicap to take into account and it is the access that both genders have to new technologies. In this sense, and in spite of the gaps in the use women make of technologies being bridged within the band ranging from 16 to 24 years old (INE, 2019), the gender digital divide continues; hence, inequalities still remain regarding the uses and knowledge of different types of ICTs, the skills to access information, as well as the knowledge and training via new technologies.

In Spain, the highest values in this gender divide in 2019 correspond to the group from 55 to 64 years old, with 14.2% points, compared to the 4.7% found in 16-to-24-year-olds (INE 2019).

2. OBJECTIVE AND HYPOTHESIS

This work’s initial hypothesis is that the social pressure exercised by female activism during phenomena such as #Yositecreo and the general strike of women on March 8, has allowed the empowerment of a movement that, thanks to the combination of the online and offline universes, became an effective medium to denounce situations of injustice and has led to big achievements such as a new law on sexual freedom.

Basing on this hypothesis, this study aims to delve into how the Internet has facilitated the dissemination of messages of female activism, and, to this end, we focus on the emergence context of #Yositecreo, as part of a global phenomenon that began with the American #MeToo and culminated with the general strike on March 8.

Hence, we propose exploring how new information technologies provide feminism with a new medium for the proactive development of its goals, which include eradicating discrimination, promoting the fight against gender stereotypes, and raising awareness about rights issues and non-violence towards women.

In a secondary way, we are going to try to determine whether the feminist activity on social networks correspond to the objectives of disseminating calls, organizing initiatives, agenda building, and self-expression that configure the process of “mesomobilization” (Scott y Street, 2000), which fosters a strategic alliance between activists’ networks on and off the Internet to promote their proposals and reach a consensus on inclusive and representative measures for all women, which are being reflected in legislative and social changes.

3. METHODOLOGY

From the perspective provided by the hemerographic reviews, we are going to analyze how the movements #Yositecreo, derived from the trial of La Manada [EN: The Pack], or the call for Women’s strike on March 8, have found ideal circumstances on the Internet to forge alliances, to debate, and to analyze different needs, as well as to reach a consensus on inclusive and representative measures for all women.

The period chosen for analysis is six months, specifically, from November 2017 to April 2018. The reason for choosing these dates is that, from our perspective, we consider that without there being such an important precedent as the world movement #MeToo, there would not have been the proper conditions to give force and make the #Yositecreo phenomenon to go viral, a slogan that emerged in November 2017 after the Spanish writer Roy Galán posted a letter on Facebook in support of the victim of La Manada assault.

Similarly, had not this case revealed the underlying patriarchal and macho culture in the Spanish society, which is capable of hiring private detectives to demonstrate the victim’s “bad reputation”, the feminist revolution on March 8 would not have happened, let alone the demonstrations against the controversial sentence given to La Manada, which defined the political and social agenda of March and April of 2018.

The method chosen to approach this research problem uses qualitative techniques, as well as a literature review of the existing relationships between feminism and the Internet, in order to carry out an investigation more adjusted to the communicative reality.

To this end, we proceeded to conduct a literature review, a “type of scientific article that, without being an original work, collects the most relevant information on a specific topic” (Guirao et al., 2008, p.3), allowing us to frame the topic within a theoretical context to subsequently carry out a thorough work of documentation and monitoring of news related to the movements here presented in order to explain how women have found an ideal opportunity on the internet to forge alliances, to debate, and to mobilize.

From a theoretical perspective of interpretivism, we have monitored the news published in the national digital press regarding both movements to later proceed to elaborate a discourse based on Van Dijk’s approaches (1980), underpinned by the summary of the ideas embodied in the statements and the grouping of ideas to establish the sense of the text in its entirety.

In a complementary way, we have proceeded to analyze the role played by social networks and instant messaging platforms in what is called a “collective action repertoire”, which refers to the actions performed by citizens when they intervene in a conflict, as well as knowing what to do and what others expect them to do (Tilly, 2009), and how the incorporation of hashtags into the activist strategies has not only achieved greater outreach for the movement, but has also “enhanced activist discourses that have changed to adjust to the digital public sphere” (Núñez-Puente et al., 2016, p. 66).

Similarly, we wanted to see the impact that the 8M women’s strike has had on the international press, hence, we have proceeded to monitor the news in the main European newspapers: the French newspaper Le Monde, the British The Guardian, and La Repubblica in Italy, as well as the impact it has had on the American press (The Washington Post and The New York Times).

4. RESULTS

In October 2017, we witnessed the birth of a movement that has gone viral on social media and that has helped women who have been abused to report it. #MeToo is the hashtag that many women have used to explain their experiences, especially after the female actor Alyssa Milano invited women from all over the world to report cases of abuse and media harassment on Twitter.

In fact, #MeToo is not new, it originated a decade ago, when activist Tarana Burke started a movement called the “Me Too Movement” focused on young women who had been victims of sexual abuse, assault, or exploitation. However, ten years later, the phenomenon went widely viral after the disclosure of producer Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse scandal, who was accused in important news reports of The New York Times and The New Yorker newspapers of “behaviors that range from harassment through to rape, according to complaints made by more than 40 women” (Llanos, 2017).

The impact of social networks has been such that just three days after, Milano’s post received 65,000 comments on Facebook and had been mentioned almost 8 million times. This is mainly thanks to the role played by celebrities, first as victims, and then as defenders. So much so that the #MeToo movement went beyond the borders of Hollywood and women from all over the world joined forces to make a phenomenon that is not isolated and that happens in all social spheres visible.

As per Ezy Insights (2018), media across the world published about #MeToo almost 4,000 times a day in mid-October, 2017, reporting even more on this trend than on fires and hurricanes. On average, #MeToo was mentioned 1,100 times per week in comparison to the 570 times that fake news were mentioned and the 250 times for the Grenfell Tower fire in which 71 people died.

On a global scale, #MeToo was trending topic on Twitter in at least 85 countries, including India, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom. Its impact was such that even some countries had their own translations, such as France where journalist Sandra Muller posted, on October 13, her own experience in just 23 words and spoke of “son porc” (her pig), a message that was retweeted 2,800 times and liked by 2,320 people (Bekmezian, 2017).

In France, using the hashtag #BalanceTonPorc, this social network was filled with stories from women describing similar events with anonymous hierarchical superiors at their jobs or incidents of harassment on the streets, which even provoked demonstrations of solidarity from men.

The impact was also noticeable in Italy, #QuellaVoltaChe, Canada #MoiAussi, and Spain with the hashtag #YoTambién.

Together with the impact generated on social networks, the #MeToo campaign gained special prominence when the harassment accusations went beyond cyberspace to impact directly on companies. In this sense, October 5, 2017, was an important date. That day, journalists Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey published an article in The New York Times titled “Harvey Weinstein paid off sexual harassment accusers for decades”. Weinstein was fired from his own company three days later.

This would be the starting point of a movement that has caused many Hollywood actors to experience work ostracism (Hollywood Reporter, 2017) due to similar cases; such as Kevin Spacey, who was also accused of sexual harassment, forcing Netflix to cancel the production of the hit series House of Cards.

Journalist and broadcaster Charlie Rose, Louis C.K., Dustin Hoffman, directors such as Brett Ratner and James Toback, or John Lasseter, who left his position as chief creative officer of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios at the end of 2019, are some of the names involved in abuse cases that have caused changes in the management boards of companies such as Tesla and SpaceX.

4.1. La Manada and #Yositecreo

Beyond the individual harassment claims within the film industry, the #MeToo movement has caused a profound impact on the overall consciousness of the population, since it has revealed the fact that sexual harassment is “ubiquitous in a macho society that objectifies women and endorses rape culture” (Coronado, 2017).

However, there are few studies in this regard, in fact, the most recent figures are from 2014 and come from a study conducted by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, which estimates that 120 million women around the world have had to endure unwelcomed kissing, hugging, touching, sexually suggestive comments, sexually explicit messages, or exhibitionistic behaviors at some point in their lives (FRA, 2014).

The disclosure of abuses through #MeToo has placed this issue at the center of the agenda setting of many governments, starting with the North American one, where Californian lobbyist Samantha Corbin founded the group We said enough, which has reported up to 147 cases of sexual harassment that happened in the Capitol corridors, causing the resignation of a senator and three assemblymen, and even the approval of laws that protect accusers and the explicit prohibition of out-of-court settlements for this type of cases.

The consequences of #MeToo have also reached Europe, causing countries like Sweden to change drastically their criminal law regarding rape, in which it is no longer necessary for it to be the result of violent or intimidating actions, from now on, it is forbidden to have sexual relations with someone who has not explicitly said yes or who actively demonstrates their willingness to participate (Sen, 2018).

Consent in the face of resistance is the pillar of the feminist theory and has become the cornerstone of #Yotambién in Spain, a movement that has been championed by politician Teresa Rodríguez, female actor Clara Lago, police officer Luisa Velasco, and journalists Ana Alfageme and Alejandra Agudo, who broke their silence in 2017 and shared their stories of being sexually abused.

According to the director of the Agencia de Comunicación y Género [EN: Communication and Gender Agency], Isabel Mastrodoménico:

To speak out means to break the macho stereotype that blames and holds the victim accountable for a situation that she has not caused. Society teaches us women to take care of ourselves so we do not get raped or assaulted, but it does not teach men to respect us. We are the ones to bear the blame and it makes it difficult for women to speak about what has happened, not only due to the tremendous burden of what has been experienced, but also having to tell it and face all kinds of judgments from third parties after doing so (Coronado, 2017).

Digital technology appropriation has managed to make the potential of the Spanish feminist activism to communicate and question mass audiences visible. In our country, the #MeToo movement has had a profound impact as a result of the controversial case of La Manada, which has spotlighted a generalized and little-known problem such as the rapes and sexual assaults that are perpetrated during popular festivals in Spain, and only 20% of the cases are reported.

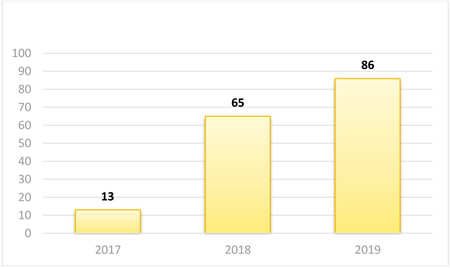

Multiple-perpetrator sexual assaults have soared over the last couple years. According to figures from Geoviolenciasexual (2020), during 2019, 86 assaults were registered in Spain (See Figure 1), which added up to the cases registered in the two years before; accumulate 164 over these three years. However, there could be many unregistered cases, since there are no official numbers and the website has conducted its study based on articles and journalistic news that collect publicly known rapes or sexual assaults.

Source: geoviolenciasexual.com

Figure 1. Sexual assaults in Spain.

In this sense, the Federation of Sexual Assault Victims Assistance Centers (CAVAS), thinks that “only one out of six rapes becomes a complaint in Spain, hence the numbers in the report neither represent nor get close to all the cases perpetrated and reported” (Reguero, 2018).

This increase also coincides with the rise in crimes against sexual freedom, which according to the Crime Rates Report from the Ministry of the Interior (2019) increased by 11.3% over the past year. Sexual assaults with penetration rose by 10.5%, while the rest did so by 11.4%.

These figures reveal the social control and limited action to which women in Spain are subjected to due to machismo, and that originated, as per Graciela Atencio, coordinator of the GeoViolenciaSexual report (2020), in hegemonic pornography, namely, sex education through Internet pornography.

According to Reguero (2018), gang rapes derive from the depiction of gangbangs, in which groups of three or more men have sex with just one woman, contributing to reinforcing the male imaginary by which women’s bodies are a territory meant to be conquered.

Within this context, the case of La Manada has gained special importance because:

It has all the paradoxes of a legal system revealing its most patriarchal side: the victimizer is treated with a myriad of presumptions while the victim not only is generally prevented from obtaining justice, but she is also virtually condemned, not by a court, but by a relentless popular jury, willing to deny the violence committed against her and saddle her with lots of stigma and discrimination (Wiener, 2018).

The La Manada trial focused on whether or not there was consent from the victim, which generated an unprecedented movement of support for the victim on social networks through the hashtag #Yositecreo, but also on the streets, where there was a massive and overwhelming response from citizens in cities such as Barcelona, Madrid, Zaragoza, Seville, Granada, and Huelva, where thousands of people did not hesitated to denounce the macho attitude of justice and the media around this case.

The different calls managed to surpass all expectations by bringing together women of all ages to demand the inclusion of sexual assaults in the Gender-based Violence Law, so trials would be conducted in specialized courts, and to criticize the controversial report that a private detective prepared using information of the victim’s activity on social networks after she made the complaint.

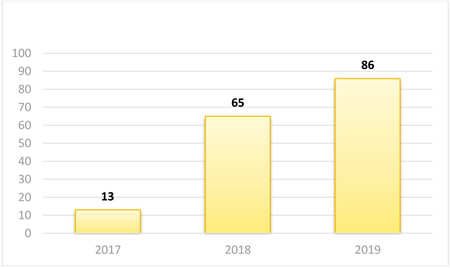

The critical point of this process occurred on April 26, 2018, when justice sentenced the five members of “La Manada” to 9 years in prison over the crime of continuous sexual abuse and not for rape, even with a particular vote in favor of acquittal. The verdict provoked great outrage in the Spanish society, and to make it noticeable, they organized dozens of mass meetings in different locations of Spain under the slogan “La manada somos nosotras” [We are “the pack”] (See Figure 2).

Source: elboletin.com

Figure 2. Call for the demonstration “‘La manada’ somos nosotras”.

This controversial verdict demonstrated the Internet’s capacity to “facilitate communication, interaction, and organization processes of social struggles, eliminating space-time barriers and facilitating just and necessary achievements” (Fernández Rincón, 2019, p.72). Immediately, #Yositecreo was used again by feminist collectives to repudiate, this time, the macho aggression of the Spanish justice decision and the constant struggle of women around the world against gender-based violence.

This hashtag had such a social impact that even the Carmelitas Descalzas nuns of Hondarribia (Guipúzcoa) joined and used it in a moving message that generated more than 1,300 comments, 14,000 reactions, and was shared more than 15,000 times (See Figure 3).

Source: Facebook.

Figure 3. Carmelitas Descalzas of Hondarribia Facebook post.

With almost a million and a half potential impacts, #Yositecreo managed to merge symbolically people’s trust in this young woman and their being fed up with women being blamed for suffering sexual violence (Núñez-Puente & Fernández-Romero, 2019, p. 389). Similarly, it focuses on the fact that the Spanish jurisprudence is obsolete, since the concept of “consent” is tied to physical considerations, such as the absence or presence of resistance, or the lack or existence of pain during the sexual act.

Through social networks, feminists associations denounced this verdict, assessing it as particularly negative, and alongside national and international celebrities, they took the cyberspace to assert their discontent and demand training in gender perspective from the judges, just as stated in the State Pact against gender violence. This is the case of the female actor Jessica Chastain, who posted on her Twitter account: “Under the Spanish law, ‘the minor crime of sexual abuse differs from rape in that it does not involve violence or intimidation’. No intimidation? Five strangers taking an intoxicated woman to an unknown location is incredibly scary and intimidating. How many women die every year?”

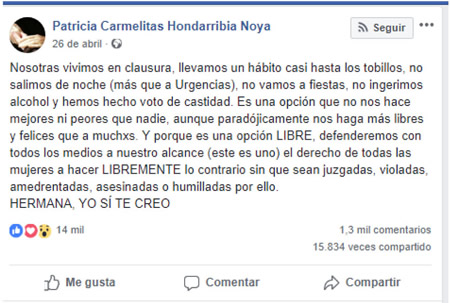

Hashtags such as: #EstaEsNuestraManada, #Niunamenos, #JusticiaPatriarcal, #NoesNo, #LaManadaSomosNosotras and #Yositecreo were trending topics on Twitter throughout the entire day of April 26 (See Figure 4), and the connecting link used by many well-known faces from very different fields such as politicians Pedro Sánchez, Pablo Iglesias, and Carolina Bescansa; female actor and director Leticia Dolera; television presenter Eva González; influencer Laura Escanes; singer Alejandro Sanz, or journalist Jordi Évole, among many others, to fight against gender-based violence and to end injustice.

Source: Twitter.

Figure 4. Trending Topics of April 26, 2018.

The next day, the online and offline social pressure caused the Government spokesman, Íñigo Méndez de Vigo, to announce the order of a technical study on whether the classification of the crimes embodied in the Penal Code on sexual assaults was adequate and this resulted, in March 2020, in the preliminary draft Organic Law on the Comprehensive Guarantee of Sexual Freedom, which regulates up to three types of harassment: including the occasional one; not repeated but sexist or sexual one, which will be punished with penalties of permanent location; ‘stalking’ or continuous harassment; and sexual harassment (Gil, 2020).

As per the Minister of Equality, Irene Montero, “the law of ‘only yes means yes’ is the law of the feminist movement” (Martín, 2020), but it is also the slogan that summarizes the new criminal model included in the Istanbul Convention, signed by more than 20 State members of the European Union in 2011, at the forefront of feminist legislation in sexual terms, and which clearly states that “consent must be given voluntarily as the result of the person’s free will assessed in the context of the surrounding circumstances” (Sen, 2018).

4.2. #8M Strike

Influenced and framed by an international context that promoted the development of global feminist awareness, the strike of March 8, 2018 placed Spain at “the forefront of the global feminist movement” (Ideograma, 2019, p.24) and the columns published by the international press were proof of this, putting the call’s success on the front pages of the world.

Thus, The Guardian (2018) underscored the high participation (“More than 5 million join Spain’s ‘feminist strike’, unions say”), Le Monde (2018) highlighted the support from social and union movements (See Figure 5) to “stop the world”, while the Italian newspaper La Repubblica (2018) pointed out that it was “the largest feminist struggle demonstration”.

Source: lemonde.fr

Figure 5. Piece of news published by Le Monde.

Meanwhile, The Washington Post (2018) pointed out women’s claim “to protest unfair wages and domestic violence by collective banging on pots”, while The New York Times (2018) published a special piece titled “International Women’s Day 2018: Beyond #MeToo, With Pride, Protests and Pressure”, highlighting women’s labor and domestic strike.

Spain changed on March 8, 2018. 123 demonstrations, 192 protests, and 185 actions give an idea of the follow-up of a strike whose objective was to demonstrate that without women the world stops because without them there is neither production nor reproduction. The general strike, aimed at half the population, was not only focused on the work field, it was also a healthcare, student, and consumer strike, and was based on the historical precedent strike led by 90% of the women in Iceland in 1975, who brought the country to a standstill and caused a turning point in the Nordic Island.

The manifesto supporting the 8M strike was agreed on in a 400-women meeting held in Zaragoza in January. In it, women demanded the end of aggressions and macho violence; fair pension payment; public, secular, and feminist education; and appealed for “intersectional feminism” (Corral, 2018), which ranges from paid work, through exercise of women’s rights, to citizen education or participation.

The so-called “third-wave feminism” began in the 1990s, when the pioneers in the fight for equality had already achieved a myriad of rights: suffrage, entry into the labor market, access to traditionally male professions… However, as stated by Heredia (2018), “complaints were missing, abused women needed to have a voice”, and, above all, concepts such as wage gap, glass ceiling, sexual harassment, or obstacles to conciliation needed to be brought to light.

Part of this revolution came from the #MeToo movement, considered to be the fastest social change in the past recent decades. Due to this phenomenon, the feminist revolution organized via social networks began to prepare, in Spain, a strike and several demonstrations that can only be compared to the ones rejecting the terrorist group ETA and the 15-M movement.

The 8M movement in Spain has a unified platform that centralizes information and material resources, and facilitates communication and dissemination of scheduled events and demonstrations. Furthermore, in the past two years “it has been visibly enriched thanks to the co-creation of content and resources” (Fernández Rincón, 2019, p.71). However, this movement’s success was due to a combination of direct and indirect interaction.

Young women’s familiarity with social networks makes them an ideal tool via which they get involved in social participation, especially if it is an issue that requires solidarity and that concerns them deeply. Facebook has played an essential role in this. This social network has allowed generating a cohesive community in which the feminist debate is active and endogamous, which permits making many complaints visible, and, most importantly, facilitates capacity for collective mobilization.

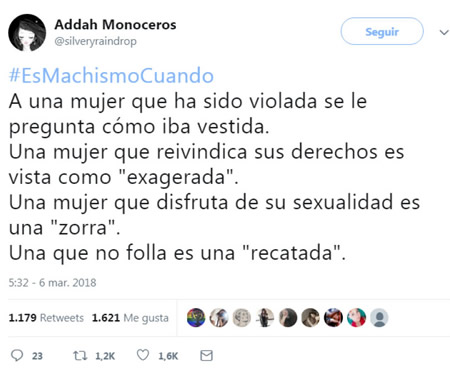

However, in the 8M strike, their main weapon was Twitter. Two days after the feminist call, thousands of tweets turned the hashtag #EsMachismoCuando (See Figure 6) into the main trending topic at a national level. The little bird’s social network was filled with stories of women denouncing the patriarchal behaviors they have to endure daily, but also comments from users who disapproved of this “through incitement, and even trolls who, with insults and contempt, have shown how necessary this debate is” (Público, 2018).

Source: Twitter.

Figure 6. Tweet posted using the hashtag #EsMachismoCuando.

On March 8, the feminist strike was shared and vindicated through 38 hashtags that resulted in easy and acceptable slogans for the whole society, such as: #Estamoshartasde, #DiaDeLaMujer, #8deMarzoHuelgaFeminista, and #El8demarzoyoparo. All of them became trending topics. The manifesto “las periodistas paramos” [we female journalists strike], signed by almost 4,000 professionals, was also tremendously important, especially due to the visibility given by the media and the stoppage of top-rated programs.

In total, almost two million messages were shared that day; out of which 85% were retweets (Ideograma, 2018), making Día de la Mujer [EN: Women’s Day] a trending topic during the entire day. The value of these messages lies in the fact that women could share their personal experiences, which allowed creating a kind of mutually shared experiences awareness.

Social networks have played an indispensable role in female empowerment, and, in this sense, specialist in Modern History, Franco Ruiz, states that:

This moment is as important as that of the British suffragettes, who realized that they were changing history. We have awakened. This is global. This step is huge. It is a milestone because the patriarchal system did not expect this new uprising of women who want absolute equality (Yankee, 2018).

In this same line, Sánchez-Duarte and Fernández Romero (2017, p.900) argue that the Web “enhances the sense of community and the democratization of the dissemination and visibility of more diverse feminist subjects”. Thanks to social networks, Beatriz Ranea affirms that, “we have reached previously unattainable contexts” and this is clearly seen in the fact that when “an unfair verdict is given, that very same afternoon a demonstration is organized” (Llorente, 2019).

Social networks allow promoting and consolidating behavior models that are swiftly imitated, which is why they permit establishing collaborative ties and generating spaces for public debate. In the case of feminist collectives, they have found their main platform for debate on Facebook, a means of lobbying on Twitter, and a platform to create, expand, and engage their community on Instagram (Cordero, 2018).

For their part, WhatsApp and Telegram have become the ideal media to share posters and make calls for action. Their main purpose is to serve as a digital repository of images, news, and messages, but it has also become an important forum to debate and spotlight issues such as the wage gap that women must endure throughout their whole work lives and, which is, specifically, 22% compared to men’s average wage (INE, 2019).

In Spain, parity has yet to be achieved, but many voices have spoken to denounce this problem; in fact, the 2018 Goya Awards (February 3) was filled with red fans with the hashtag #Masmujeres [More women] demanding higher presence of women in the Spanish cinema, an industry in which, according to data from the Association of Women Filmmakers and Women in Audiovisual Media (CIMA), there are only 7% of female directors and 2% of female photography directors.

The plurality of these activist actions lived during 2018 has finally impacted on the Spanish politician class, urging them to work for the sake of alleviating the inequality between men and women. Thus, on March 7, 2019, the Official State Gazette (BOE) published the Royal Decree-Law 6/2019, on March 1, on urgent measures to guarantee equal treatment and opportunities between women and men in employment and occupation, which aims to resolve the wage gap and tackles all discrimination problems, included a balanced distribution in leadership positions.

5. DISCUSSION

2018 will endure in time as the beginning of women’s empowerment era. Thanks to social networks, women have spotlighted the structural gender barriers that have limited their individual and collective capacities, and have claimed, in terms of equality, access to resources and to decision-making processes in all the fields of their personal and social life.

There are many achievements attained due to the social pressure exercised by a group that makes up half of humanity, and that asserts its capacity to fight for its rights and effective equality in access to basic resources. To this end, communicative processes on the Web have become channels for information dissemination with enormous potential for real interaction, to the point of promoting social transformations and achieving specific political objectives.

The strategic alliance of online and offline networks has strengthened the fight against gender-based violence towards women, generating an interactive and proactive cyberactivism that has even managed to transcend the private business and politics world, as well as it has allowed questioning judicial decisions and provoking a national strike in response to the physical, psychological, symbolic, economic, and patrimonial violence experienced by women.

Movements such as #Yositecreo or #8M have served to put an end to decades of apathy towards participation in Spain. Women have decided to raise their voices and say “enough” thanks to the drive of a sector of very young women who have become highly organized activists thanks to social networks and instant messaging tools, which have played an important role in uniting women against common problems, but also giving them a voice to highlight the daily problems that women of all social spheres endure.

Women who have been educated based on the strong belief of equality but who at the moment of truth have found that there is no real equality; that women have a glass ceiling difficult to break, that even with equal hours and workload they earn less than their male peers, that they have to continue fighting for family and work conciliation, that they bear the emotional burden of their homes and, on top of that, have to endure being harassed and dread that men will put an end to their freedoms.

There are still many challenges ahead; 2018 has only been another step in the fight for equality that women have been demanding since the 19th century, and that, for now, continues to be the pivot on which the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development revolves, since, according to data from the World Bank (2017), on a global scale, women represent 28.8% of people who dedicate themselves to research, while only 1 in 5 countries has achieved gender parity in this regard, in 49 countries there is still no legislation on domestic violence, 45 countries do not address specifically sexual harassment, and in 37 countries rapists are still legally absolved if they are married to or subsequently marry their victim.

6. REFERENCES

AUTHOR:

Marián Alonso-González

Marián Alonso González holds a Ph.D. in Communication by the University of Seville (2008) with a Doctoral Thesis addressing the technological change in ABC de Sevilla. She is member of the Asamblea de Mujeres Periodistas de Sevilla and the Censo de Expertas. She combines her professional work as a Communication Technician at Adif with her teaching work as an Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Communication of Seville, where she teaches about new technologies and writing. She specializes in Social Networks; she has oriented her research work to fields related to Communication 2.0, Journalism 3.0, social audiences, and new multimedia and interactive languages.

malonsog@us.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2676-0449

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?hl=es&pli=1&user=pTW9yp0AAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alonso_Marian

Scopus ID: 57000544900

Academia.edu: https://us.academia.edu/Mari%C3%A1nAlonso